A Bite-sized Look at Progress on Good Food Infrastructure

Food system infrastructure makes possible every step from growing food to selling and eating it, and it is a key priority area of Michigan Good Food Charter.

This is the third in a five-part series on progress made on the agenda priorities of the Michigan Good Food Charter. In March, we looked at progress on Good Food Access and in May we explored progress on Farms and Farmers.

Creating a food system centered on good food—food that is healthy, green, fair and affordable— includes shaping the infrastructure, or building blocks, of Michigan’s food system.

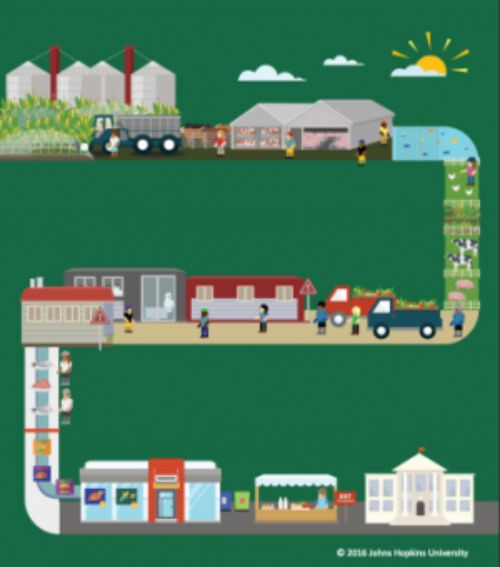

Food system infrastructure underlies every step from growing food to selling and eating it, and it is a key priority area of Michigan Good Food Charter.

According to the Food System Infrastructure Work Group Report, food system infrastructure covers everything needed in the agri-food supply chain of activity between the consumer and the producer. These supply chains include:

- Production (e.g. seeds, equipment)

- Processing (e.g. canning, washing, freezing food)

- Aggregation and distribution (e.g. storage facilities and delivery trucks)

- Retailing (e.g. grocery stores, restaurants)

- Marketing (e.g. promotional materials including billboards and commercials)

- Capital (includes financial, natural, human and social capital)

The priority areas listed below are a few of the Charter agenda items related to improving food system infrastructure. The examples of progress are a selection from the 2016 Good Food Charter report card.

Priority 5 – Establish food business districts.

- The Michigan Food Hub Network, now in its fifth year, provides information, training and collaborative opportunities for regional food hub members and affiliates. As of 2016, more than 440 different people had attended a food hub meeting in Michigan. Survey responses from participants indicate the network has helped form business-to-business partnerships and secure grant or loan funding, among other benefits.

- A Detroit Food and Fitness Collaborative economic analysis of Detroit’s Food Systemshowed that in 2014, Detroit’s food system was producing $3.6 billion in revenue and employing more than 36,000 people.

- Taste the Local Difference (TLD) has established itself as northwest Michigan’s local food marketing agency by branding locally made and sourced products. Over 1,300 farms and businesses participate in TLD and the agency also now manages a magazine, smart phone app and website to help connect consumers with local products and producers.

Priority 15 – Direct $10 million to regional food supply chain infrastructure development investments through the Michigan state planning and development regions or other existing regional designations.

- The Michigan Good Food Fund (MGFF) is a $30 million public-private partnership loan and grant fund for good food enterprises (including growers, distributors, processors and retailers) that benefits underserved communities across the state. MGFF also provides business assistance services and offers multiple financing options to support good food business ventures.

- The Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) offers a Value Added/Regional Food Systems Grant program, which funds projects focused on value-added food processing, food hub development and food access.

Priority 21 – Contingent upon further market assessment, establish a state meat and poultry inspection program.

- The Michigan Meat Association continues to support and advocate for regulations concerning small scale meat processors in Michigan.

- The Michigan Meat Network was launched in the spring of 2016 by the MSU Center for Regional Food Systems to serve livestock producers, meat processors, distributors, and food buyers and professionals. The MMN helps network members to connect, explores viable market options and addresses regulatory challenges faced by local and regional meat stakeholders.

Priority 23 – Incorporate food and agriculture into local economic development plans.

- Agriculture is increasingly regarded as an economic development engine at the local and regional economic development levels. Several of the state’s 10 Prosperity Regions have economic development strategies that include an agriculture component. For example, Flint developed and is implementing a Master Plan for Sustainable Flint, and the Master Plan for Grand Traverse County includes natural resource conservation and agricultural land preservation.

Priority 24 – Examine Michigan’s food- and agriculture-related laws and regulations for provisions that create unnecessary transaction costs and regulatory burdens.

- MDARD has formed an Interdepartmental Collaboration Committee (ICC) Subcommittee on Food Policy, which serves as a statewide action team to support food policy discussions around the goals of the Good Food Charter.

- The Group GAP (Good Agricultural Practices) has established a team to make the program a statewide initiative and helps farmers obtain GAP certification.

- Two bills, Senate Bill 144 (now Public Act 142 of 2015) and House Bill 4017 (now Public Act 41 of 2015), amended the Food Law to alter inspection regulations for low-risk food establishments and to limit legal ramifications for food businesses who donate food, respectively.

These examples are just some of the ways that good food partners across the state are improving food system infrastructure to reach the goals of the Good Food Charter. To read more success stories like these, see the Good Food Charter 2016 Report Card.

A note on measuring Charter progress: MSU CRFS continues to partner with the Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition to develop a shared measurement system to enable partners across the state to collect similar data to better understand progress on key indicators for the Charter goals, both locally and statewide.

Print

Print Email

Email