Avian botulism and the Great Lakes

Type C avian botulism confirmed in East Grand Traverse Bay August 2014

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) confirmed on August 12, 2014 that about 24 mallard ducks died from type C avian botulism along the southern shore of East Grand Traverse Bay. The ducks were found in a localized, small area near the Acme Township/East Bay Township shoreline in Grand Traverse County.

What is avian botulism and should we be concerned?

Avian botulism is a food poisoning whereby waterfowl ingest a toxin which is produced by the naturally occurring rod-shaped bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Typically, these native bacteria live in a highly resistant spore stage and are of no impact to fish and wildlife; however, under the right circumstances (usually anaerobic conditions), the bacteria will germinate, produce and make bio-available one of nature’s most potent toxicants. The toxin causes muscular paralysis. Often the birds are unable to hold their head up and may drown or die from respiratory failure. Avian botulism is also known as limberneck, due to the bird’s inability to hold up its head.

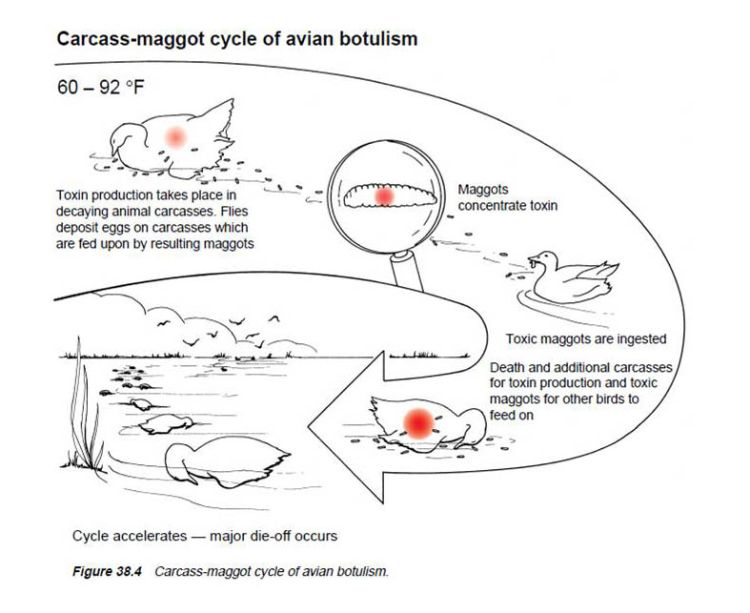

While small invertebrates (often maggots) are not impacted by the toxin, they often serve to pass the toxin up the food chain. A rotting carcass that has the botulism toxin in it and is decomposing along the shore can often be a source for maggots, and other scavenging birds such as gulls can possibly get botulism. This maggot-cycle is particularly important for type C botulism.

What is type C botulism vs. type E botulism?

Type C avian botulism is the neuromuscular disease which typically affects dabbler ducks, and possibly other shorebirds, that forage in the mud in both inland and Great Lake coastlines (see the poster from Michigan Sea Grant - Dabblers & Divers: Great Lakes Waterfowl) and eat invertebrates directly. Type C impacts are felt in both inland lake and pond environments as well as in the Great Lakes shorelines.

Type E avian botulism usually impacts diver ducks in the Great Lakes where they dive deep and eat fish/mussels. Avian botulism outbreaks (type E) have occurred, with increased frequency in Lake Michigan along the northwest Michigan region since 2006, typically during the September-October-November time frame.

The mallard dabbler duck is the most abundant local duck in the Grand Traverse Bay region with strong population numbers and is the single species that was affected in the recent outbreak confirmed by the DNR. It is doubtful that a significant type C botulism outbreak would seriously impact population numbers of this species.

However, diving duck species such as common loons are a noteworthy species that have been impacted by type E botulism over a recent number of years. Common loons are a species of special concern in Michigan, and the full impact of the botulism kills are not known and a possible concern for loon population impacts in North America.

Michigan Sea Grant has published information and frequently asked questions concerning botulism which is applicable to both Type C and Type E, including:

- Is it safe to walk dogs on the beach after a bird kill?

If you bring pets to the shore, keep them away from dead animals on the beach. Dead wildlife may contain potentially harmful bacteria or toxins. In cases where you think your pet may have ingested a contaminated carcass, monitor them for signs of sickness and contact a veterinarian if you suspect they are falling ill.

- Do I have to wash my hands after I touch a dead bird?

Yes, you should always wash your hands after handling any wildlife. Ideally, you should also wear gloves to handle any dead animal. - Can I swim in the water?

You are not at risk for botulism poisoning by swimming in Great Lakes waters. Botulism is only contracted by ingesting fish or birds contaminated with the toxin. If you have concerns about water quality, contact your local health department or swim in a regulated beach area. - How can people who want to help clean up the beach after a bird kill best protect themselves?

People who handle dead wildlife should wear protective gear, such as disposable rubber gloves or an inverted plastic bag over their hands. In cases where a diseased or dead bird is handled without gloves, hands should be thoroughly washed with hot, soapy water or an anti-bacterial cleaner. - What is the best way to dispose of dead fish/birds in my area, especially after a botulism outbreak?

Be sure to follow local wildlife agency (e.g., Natural Resources, Fish and Wildlife, etc.) recommendations in handling dead fish and wildlife. Wear disposable, rubber or plastic gloves or invert a plastic bag over your hands when handling sick, dead, or dying fish, birds or other animals. In certain areas, burying of the carcasses is allowed, while in other areas incineration may be recommended. If birds are to be collected, they should be placed in heavy plastic bags to avoid the spread of botulism-containing maggots. The major goal should be to protect yourself, while also ensuring that the dead birds or fish are not available for consumption by other wildlife.

Any dead or dying birds that are found along the south shore of Grand Traverse Bay should be reported to the local Traverse City DNR office at 231-922-5280, ext. 6832. Staff from the Grand Traverse MSU Extension office has been involved in providing educational programs on avian botulism for several years. If you would like a program, please contact MSU Extension at 231.922.4628 or e-mail to breederl@msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email