Charles Parker Halligan’s impact on the MSU Landscape Architecture program

The individuals who started Landscape Architecture at MSU in 1898 are all but forgotten, but Professor Charles Halligan should be remembered for his arrival and his growth of the program during its’ early stages at MSU.

Born in 1881 in Boston, Massachusetts, Charles Parker Halligan (1881–1966) became an instructor in horticulture and landscape architecture at Michigan State University (MSU) when it was still called the State Agricultural College (SAC).

His career spanned from 1907 to his retirement in 1946, ending as a professor of landscape architecture. He became a full professor of landscape architecture in 1919.

Halligan graduated in 1907 from the Massachusetts Agriculture College (eventually to become the University of Massachusetts, Amherst) with a Bachelor of Science degree (a four year degree he earned in three years).

In the summer of 1903, he held a position as an assistant arborist at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston. He had been an instructor of landscape architecture while going to school in Massachusetts and had also taught at a National Farm School in Pennsylvania from 1903 to 1905.

At the time, Amherst’s landscape architecture education was a Bachelor of Science degree in Landscape Gardening, but these were formative years, eventually being changed to a bachelor’s degree in landscape architecture in 1930.

Halligan was taught by Frank Waugh (1869–1943) at Amherst. Waugh was a Midwestern/Wisconsin native who brought a sensibility for natural resource planning and recreation, as opposed to the Beaux Arts Italianate design often taught at the time at Harvard and also heavily taught at MIT.

Such a natural resource perspective was to also suit the sensibilities of Midwestern students at MSU.

Waugh is credited as the first person to complete a master’s landscape architectural project, doing campus planning and design while teaching at Oklahoma State Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University) for his master’s work at Kansas State Agricultural College (now Kansas State University), graduating in 1894 (Steiner 1989).

Halligan was greatly influence by Frank Waugh.

Formative Years: Landscape Architecture in Higher Education

At the beginning of the 20th Century, there were few places where one could study landscape architecture: MSU for an undergraduate degree, Harvard for a graduate degree, plus the schools University of Massachusetts (UMass) (1903), MIT (1900) and Cornell University (1904).

The University of Illinois started in 1907 (but had been teaching landscape gardening/garden architecture since 1868), and the University of Michigan offered their first course in landscape design in 1908 (MSU had been teaching such courses since sometime between 1863–1865 and both Kansas State University and Iowa State started teaching landscape gardening course in 1871) (Steiner and Brooks 1986).

In France, landscape design had been taught at Versailles in 1874, eventually offering a degree in landscape architecture after American universities began offering landscape gardening/landscape architecture degrees (Burley and Pasquier 2006).

New England, the Mid-Atlantic States and the Midwest were major centers of learning for landscape architecture (the core and heart of the profession—a corridor of landscape architectural sensibility). By 1910, a total of 35 students had graduated in landscape architecture across all programs in the United States (Robinette 1973), of which nine were from MSU (Andrew, Goldschmidt, Hodges, and Hazlett 1980).

In other words, more than 25% of the landscape architects in the U.S. with a landscape architecture degree came from MSU. The students were not taught one style, but a blend of styles ranging from Italianate, to French, the English Landscape School, rural development and an appreciation for the native landscape.

Michigan State has a strong claim to being the oldest continuous university landscape architecture curriculum/program/education in the world.

Although it can be claimed that some Asian schools of higher learning may have been teaching such topics centuries earlier, but they were not necessarily teaching what is considered the modern university model and may not have been teaching the full range of landscape architectural subjects as envisioned by Americans, Canadians, and Europeans — the modern university model is of German origin.

Therefore, the debate continues as to who and what can claim early beginnings in landscape architectural education.

MSU will continue to claim to offer the first full continuously offered modern university curriculum in landscape architecture leading to professional practice (1898). It will also continue to claim that it is the first university to teach a full course in landscape design (sometime around 1863–1865); while, Harvard offered the first master’s degree in a fully independent landscape architecture department and continuous graduate degree title (1900).

So Harvard’s claim to be the first in landscape architecture is a bit tenuous, but certainly they were relatively early in adopting a full curriculum (but not the first) in the subject and were strong promoters of the term “landscape architecture,” eventually being on the prevailing side of the debate for a choice of term.

Both programs graduated their first students in 1902 (MSU’s first student was T. Glenn Phillips, FASLA (1877–1945). MIT had a landscape architecture program that floundered (existing from 1900 to 1909–1910) and also graduated its first students in 1902, including the graduation of some noted women landscape architects during its time.

MIT should not be overlooked in the initiation and formation of landscape architecture education in the U.S. and continues to hire notable landscape architectural academics at its institution. The history of landscape architectural education and formation is somewhat fuzzy and debated, with several schools claiming “firsts.”

Retired MSU landscape architectural and urban planning professor Mariam Rutz with the assistance of colleagues at Cornell should be recognized for their efforts to revive and reclaim MSU’s place in the development of landscape architectural education and helped MSU rediscover its past.

It seems that some things that should be remembered are forgotten, but for institutions of higher learning the list of things to be remembered can be lengthy. It seems that those at Cornell competitively desired to correct the record before it was forgotten and assisted Rutz in asserting MSU’s position.

The reason for this may have been Cornell’s desire to establish their place in the narrative with Albert Nelson Prentiss (1836–1896), the first teacher of landscape design at MSU, who left MSU for Cornell and Liberty Hyde Bailey (1858–1954), also an MSU graduate, founder of the first horticulture department in the world “Horticulture and Landscape Gardening Department” at MSU in 1884, who also went to Cornell in 1888. At that time, Cornell University and MSU were closely affiliated with personal and educational approach.

It should be noted that in the U.S., “landscape gardening” was the preferred choice for the description of the profession back then (Steiner and Brooks 1986). It was also the preferred term in the U.K. by individuals such as Humphrey Repton.

O.C. Simonds (1920) also preferred the term landscape gardening. His vision of the profession landscape gardening included the design of highways, cemeteries, railway stations, managed forested and natural lands, golf courses, school grounds, and city planning.

Simonds spent the first 25 pages of his book, explaining why he preferred the term “landscape gardening” for the management of the natural environmental and built environment.

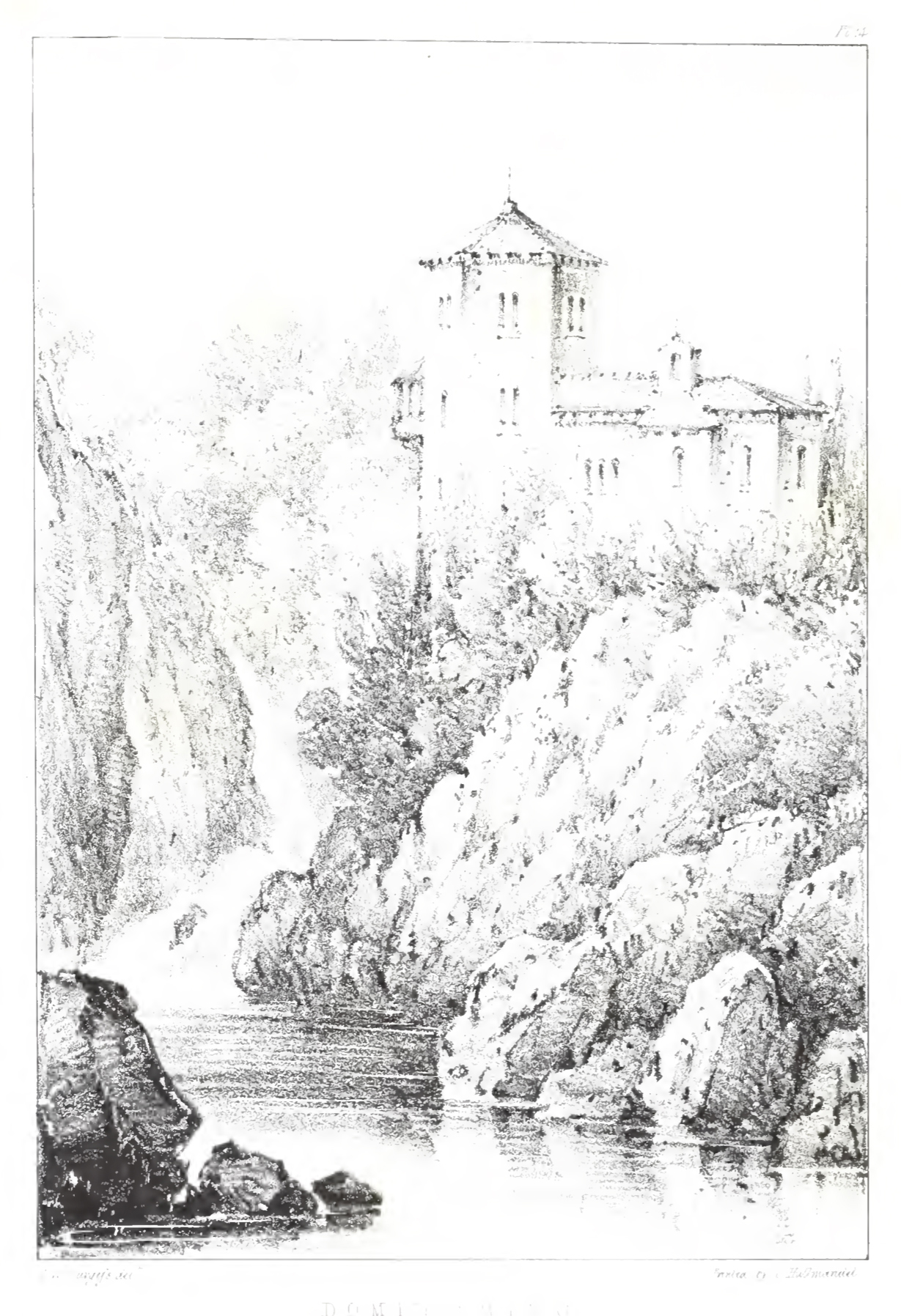

The actual term “landscape architecture” has French origins, architecture de paysage (architecture of landscape), or paysagiste (landscapist) and was first used in the English language by a Scot, Gilbert Laing Meason (1828), to describe images in Italian paintings (often in the background of religious or mythical stories) combining interesting landscape with architecture (Figure 1).

Even in Turkey, scholars at times use the term “peyjaz,” essentially pronounced the same as the French pronounce “paysage.”

In many respects this vision of architecture and landscape unified together was a continuation of the earlier painterly picturesque ideals embodied by individuals such as Humphry Repton (1752–1818) and expressed by Henry Hoare II (1705–1785) at Stoudhead (Burley and Machemer 2016).

In the 1920s, O.C. Simonds was still embracing this notion of the integration of structure and landscape (Figure 2).

Despite the claims of many, one of the unifying ideas affiliated within landscape architectural education is how many of the great schools are situated in the general I-90/I-80 American corridor.

These schools include: Harvard, UMass Amherst, Rutgers, Cornell, Pennsylvania State, the University of Pennsylvania, Ohio State, the State University New York Syracuse, the University of Michigan, MSU, Purdue, Illinois, Ball State, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa State.

It extends to nearby Virginia Tech, the University of Kentucky, West Virginia University, Washington University (in St. Louis), Kansas State, Oklahoma State University, the University of Nebraska, the University of Oklahoma, Colorado State, the University of Colorado-Denver, the University of Toronto, the University of Guelph, the University of Manitoba and the University of Montreal.

These are all great schools, with a top level of education in landscape architecture. One could attend any of them and earn a great education in landscape architecture.

The choice for a student may be more related to location/proximity and price. No other locality in the world may have such a great density in learning, scholarship and education in landscape architecture, although the eastern portion of the P.R. of China is also quickly earning such a reputation too, with an abundance of more recent great landscape architectural schools from Beijing to Hong Kong/Guangzhou.

This North American corridor belongs to the home of many great designers and intellects including: Andrew Jackson Downing, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles Elliot, H.W.S. Cleveland, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Burley Griffin, O.C. Simonds, Liberty Hyde Bailey, Frank Waugh, Aldo Leopold, Almerin Hotchkiss, and William Le Baron Jenny, and where Jens Jenson practiced.

This region should be recognized for its’ highly influential design in architecture, landscape architecture, and environmental studies. MSU is a part of this history, right in the center.

Evolving from a Department of Horticulture and in an agriculture college, landscape architecture at MSU certainly had obstacles to overcome, as the normative theoretical differences between agricultural scientists and planning/design academics can be substantial, generating friction and misunderstandings.

Such issues continue in universities across the globe, repeatedly. In many respects, landscape architecture’s academic subjects that are most closely affiliated with it are interior design, architecture, urban planning, and fine art, then engineering, horticulture, ecology and recreation, extending to social and natural resource sciences.

In the 1930s and 40s, ASLA urged landscape programs to migrate to architecture/planning colleges (Marshall undated).

Charles Halligan at MSU

Charles Halligan was at MSU during a time when he had to navigate such adversity at its highest levels – university politics can be difficult – not always collegial as different bodies of knowledge vie for resources and constantly having to educate the constant flow of changing administrators.

Universities promote what they think are in their best interest, and may ignore selected successes. At any given time, there are so many good people doing notable works, the university can be overwhelmed with possibilities for marketing and promotional materials.

Professor Halligan formed the Department of Landscape Architecture at MSU in 1923, moving landscape architecture out of Horticulture and offering a Bachelor of Science in Landscape Architecture. This occurred 25 years after MSU offered a curriculum in landscape architecture in 1898.

By the time he retired, Halligan had helped to form Urban Planning as a degree offering at MSU (1946) from a series of urban planning courses first taught in the landscape architecture curriculum in 1939, and landscape architecture was preparing to leave the College of Agriculture as ASLA had urged.

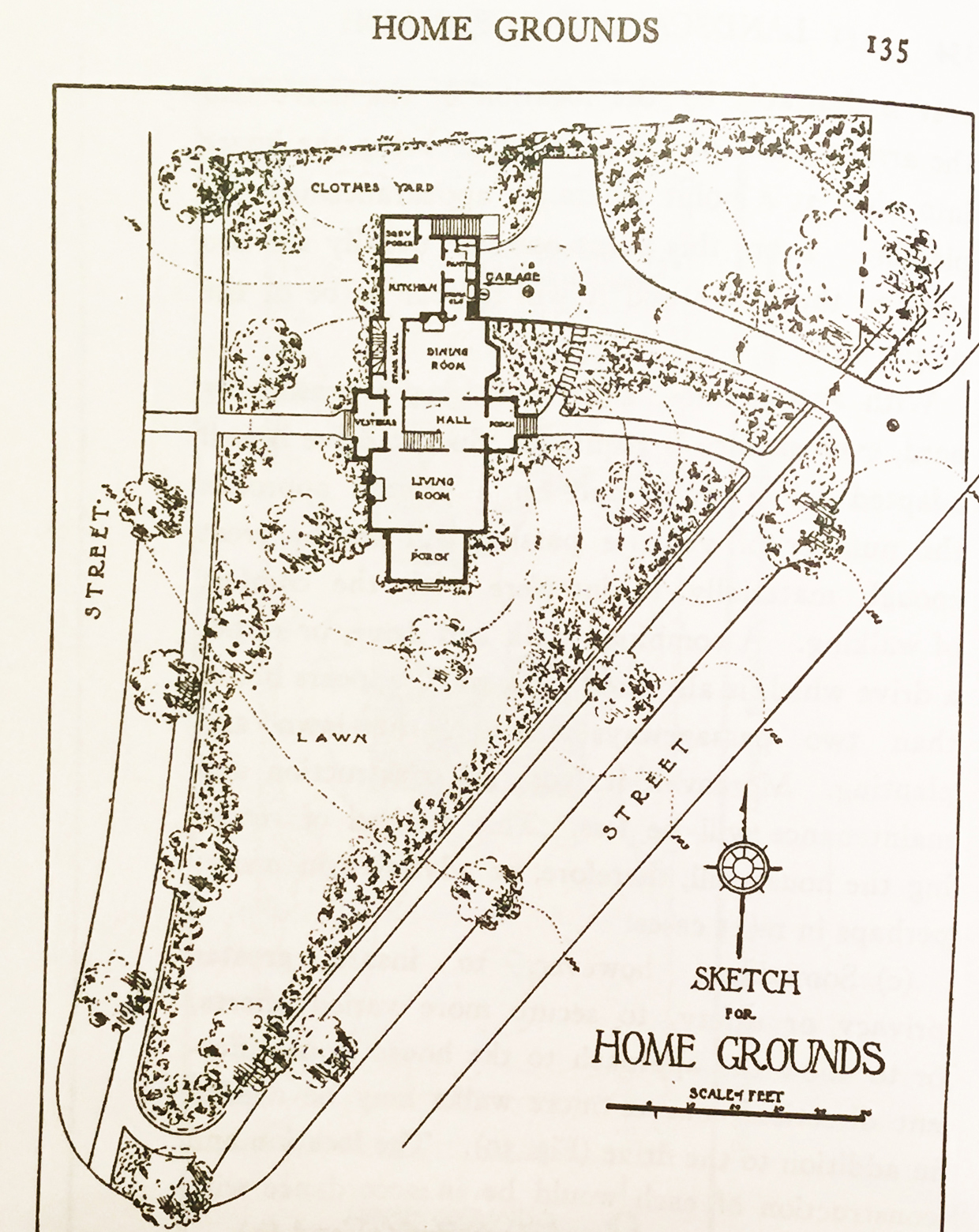

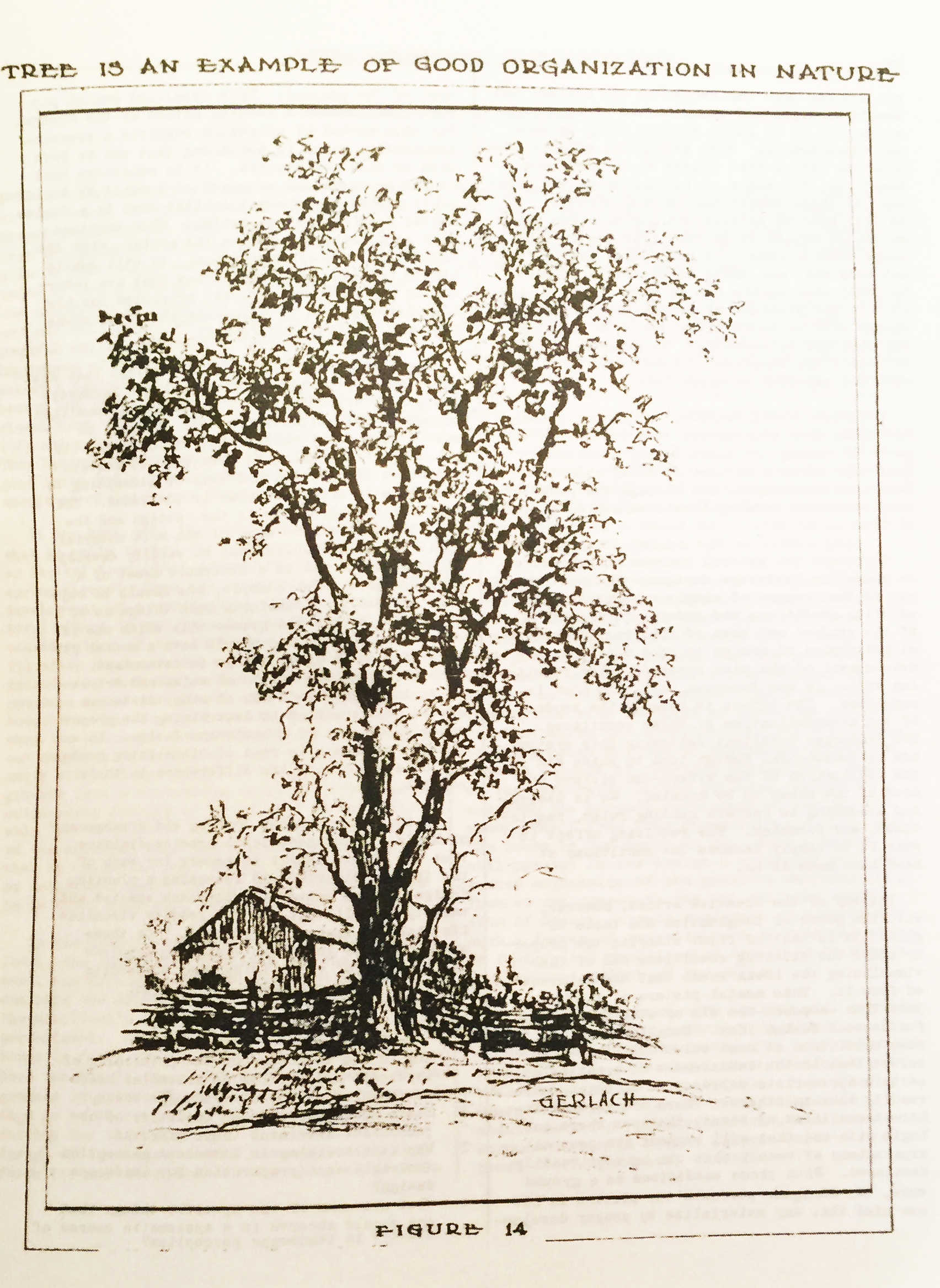

Halligan wrote a book titled Landscape Architecture, First Principles of, published in 1946 by Edwards Bros., Ann Arbor, MI, but copyrighted in 1939. He also wrote many extension publications addressing plant culture and landscape design (for cemeteries, roadways, sites).

The book is an interesting look at the profession back then. Modernism and conceptual design, ideas that invigorated individuals like Garrett Eckbo, James Rose, Dan Kiley, Thomas Church, and Roberto Burle Marx had not yet influenced MSU—as such ideas would have seemed much too revolutionary and radical for many.

Yet, in the book one can observe a transition from classical Beaux Arts training to ideas about every design being individualistic and unique and one can see a respect and appreciation for the natural environment.

In some respects the book was like a first reading and an updated version of Ossian Cole Simond’s book published in 1920, Landscape Gardening.

Professor Halligan was certainly on board with the term landscape architecture. In his book, Carl Gerlach (another MSU landscape professor) provided the sketches for the illustrations (Figure 3).

Halligan taught some of the most influence professionals in landscape architecture including:

- Genevieve Gillette (1898–1986) graduating in 1920 who worked for Jens Jensen as she was an advocate for protecting landscapes in the Midwest, especially Michigan.

- Harold W. Lautner (1902–1992) graduating in 1925 who arrived at MSU as a professor (1946–1970) when professor Halligan retired.

- William Penn Mott, Jr. (1909–1992) graduating in 1931 and head of the National Park Service (1985–1989).

- John O. Simonds (1913–2005) graduating in 1935 and author of Landscape Architecture: The Shaping of Man's Natural Environment.

- Clare A. Gunn (1916–2015) graduating in 1940, an MSU extension specialist and a professor at Texas A&M known for his book Vacationscape: Designing Tourism Regions.

Many great people have come through the MSU Landscape Architecture program.

When Professor Halligan retired, Harold Lautner became the new department chair and continued the transition in landscape architectural education. The program began to emphasize site planning specializations for recreation, urban design, commercial centers, transportation and housing with less emphasis upon residential estate design.

After WW II, the profession was evolving towards modernism. The picturesque and plants would still be important, as it remains today, but the scale of possible projects was changing, public practice would become more substantial, conceptual design would become more pervasive, new construction materials would render new techniques, intercontinental air travel would lead to projects around the world, and science would add informed input into the planning and design process.

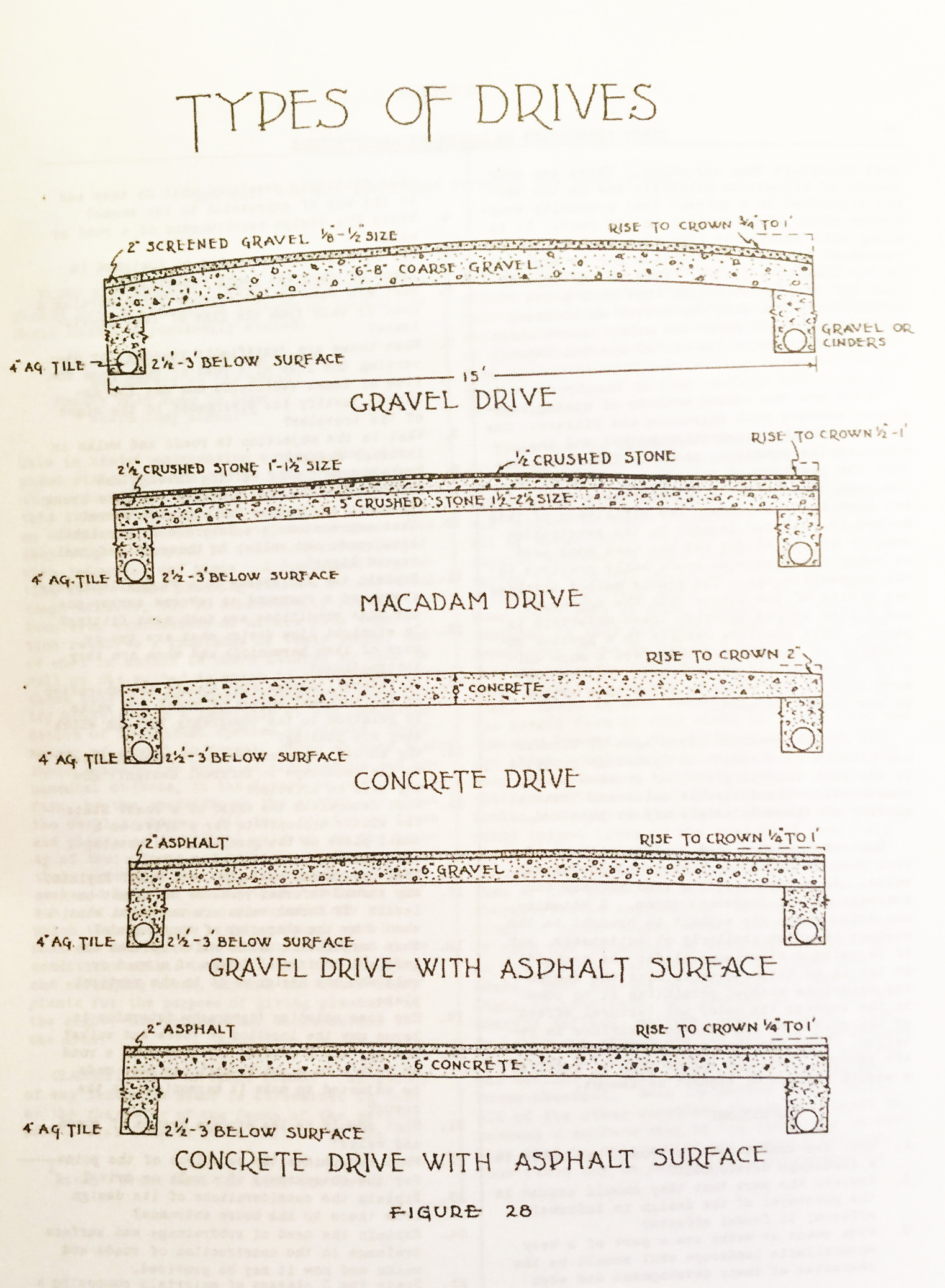

Still, there was some carryover, such as students and professionals drawing and learning about pavement/roadway cross-sections (Halligan 1946, page 95) (Figure 4). MSU students continue draw somewhat similar cross-sections in their landscape construction courses today.

During Halligan’s time at MSU, he brought many fine instructors to MSU to teach landscape architectural topics including: Carl S. Gerlach, Charlie Barr, Harold Lautner FASLA, and Myles Boylan.

In addition, Halligan did some of the professional lot layout work for the nearby subdivisions in East Lansing, Michigan, northwest of the campus, primarily the Glencairn neighborhood.

Rejecting the inflexible Greek gridiron that was indiscriminately applied to many areas of the country, the design follows land development principles previously explored by Olmsted at Riverside, Illinois, and Hotchkiss at Lake Forest, Illinois, principles that are sympathetic to land form, neighborhood building, and traffic calming.

While at MSU, Professor Halligan wrote many MSU extension bulletins, primarily horticultural in application.

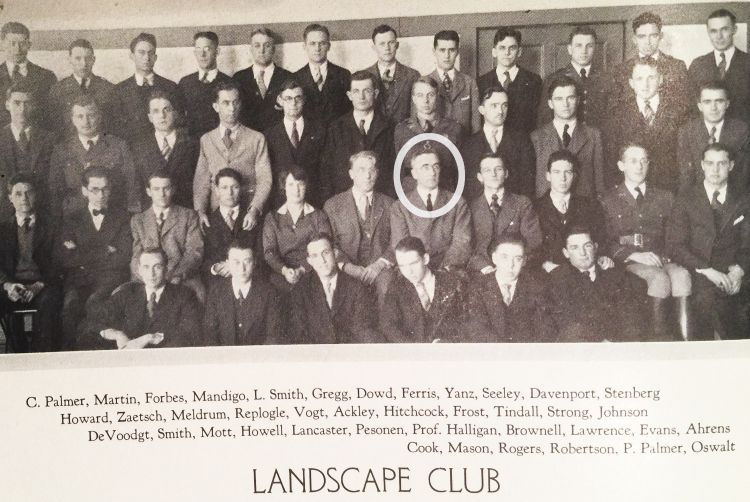

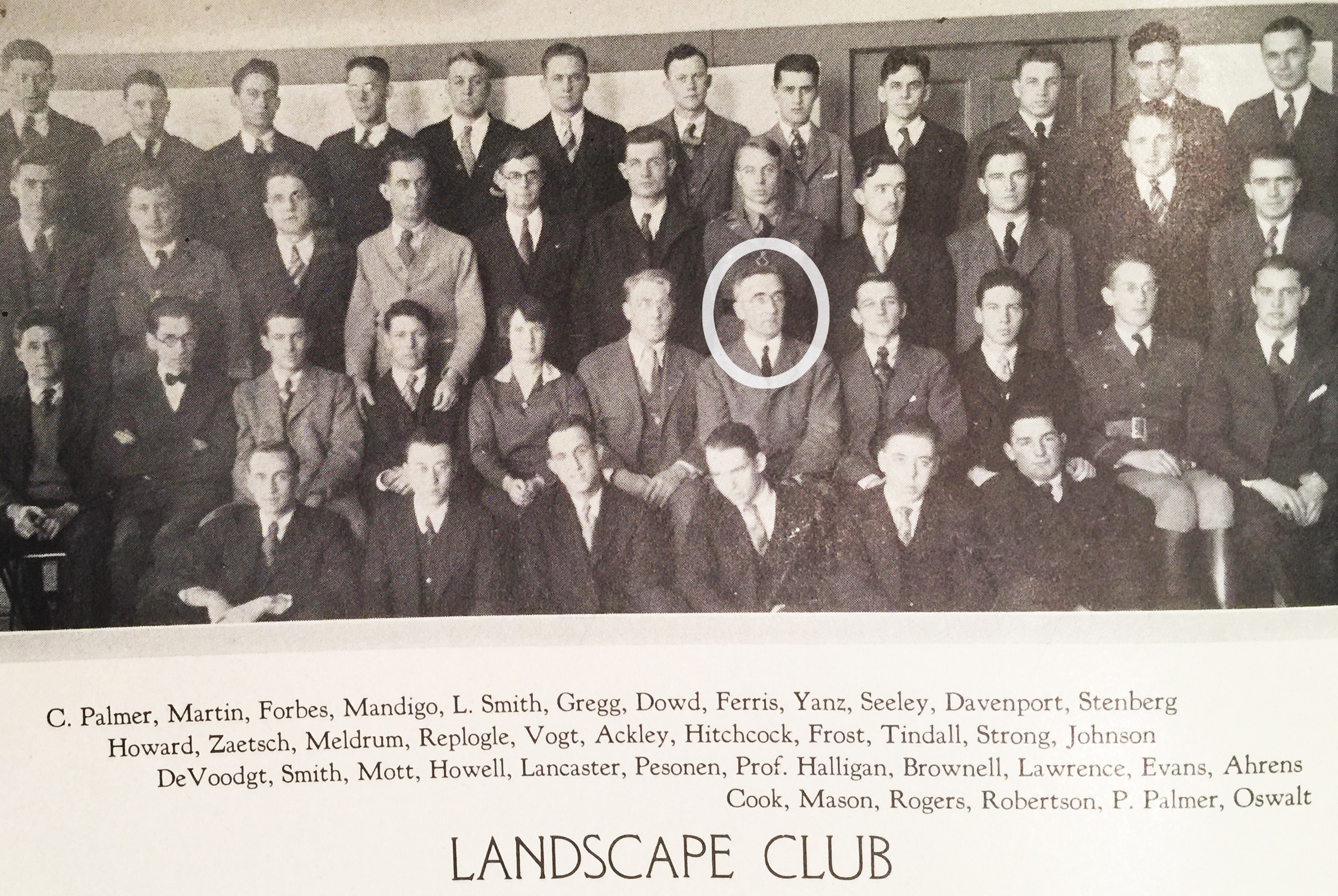

The individuals who started landscape architecture at MSU in 1898 are all but forgotten, but Professor Charles Halligan should be remembered for his arrival and his growth of the program during its’ early stages at MSU (Figure 5).

Over the years, despite MSU’s achievements in landscape architecture, the program has been somewhat modest in describing and mentioning its’ achievements.

Maybe now is an excellent time to reflect and to begin admiring the many activities of a landscape curriculum at the university level that is possibly the first in the world, more than 120 years old, and to begin to remember those who guided those achievements.

As the profession continued to grow, The American Society of Landscape Architects began to recognize the importance of science (ASLA undated) and lamented the limitations of a strictly arts and heuristic decision making process embedded in architecture, abandoning previous policies, recognizing the value of science.

The Landscape Architecture program at MSU is uniquely positioned, being affiliated with both the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the College of Social Science.

The blend of the professional practice decision making arts and the knowledge generation found in both the physical and social sciences is an important direction for the future of landscape architecture.

As in the 1860s, 1900s, 1940s and 1960s, MSU in the 2020s continues to lead the way in environment and design scholarship. At MSU we look for new faculty that can teach progressive planning and design, but who can also be fully engaged in quality research endeavors.

It takes a special person to succeed in this blend. To have full command of both the arts and sciences is not easy.

For his time, Professor Halligan did his part in moving the profession forward. He should not be forgotten.

Literature Cited

Andrew, G., C. Goldschmidt, M. Hodges, and T. Hazlett. 1980. “1980 Landscape Architecture Faculty and Staff.” College of Social Science, School of Urban Planning and Landscape Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Michigan State University.

Burley, J.B. and T. Machemer. 2016. “From Eye to Heart: Exterior Spaces Explored and Explained.” Cognella Academic Publishing, first ed.

Burley, J.B. and P. Pasquier. 2006. “From Beaux Arts to Post Post-modernism: The Parallel Educational Evolution of Two Landscape Programs from MSU and Institut National d'Horticulture-Paysage.” Innovation and Development of Landscape Education. Proceedings of the 1st International Landscape Studies Education Symposium, 28–29 October 2005, Tongji University, Shanghai, China: 266–277.

Grese, R.E. 1993. “Bailey, Liberty Hyde.” Birnbaum, C.A. and L.E. Crowder (eds.) In Pioneers of American Landscape Design: An Annotated Bibliography. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cultural Resources, Preservation Assistance Division, Historic Landscape Initiative, Washington, D.C: 9–13.

Marshall, L. Undated. “Landscape Architecture into the 21st Century.” The American Society of Landscape Architects.

Meason, L.G. 1928. “On the Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy.” H. W. Burgess (illustrator); Dennett Jacques (printer); C. Hullmandel (publisher).

Michigan State College. 1930. “The 1930 Wolverine.” Students of the Michigan State College, East Lansing.

Robinette, G.O. 1973. “Landscape Architecture Education.” Kendall/Hunt Publishers., 2 volumes.

Simonds, O.C. 1920. “Landscape-gardening.” The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA.

Spear, R.E. 1982. “Domenichino.” Yale University Press, 2 volumes.

Steiner, F.R. 1986. “Frank Albert Waugh. American Landscape Architecture”: Tishler, W. (ed.) In: Designers and Places. National Trust for Historic Preservation and the American Society of Landscape Architects/The Preservation Press: 100–103.

Steiner, F.R. and K.R. Brooks. 1986. “Agricultural Education and Landscape Architecture. Landscape Journal 5(1):19–32.

Widder, K.R. 2005. “Michigan Agricultural College: The Evolution of a Land-Grant Philosophy 1855–1925.” Michigan State University Press.

Print

Print Email

Email