Emergency forages – Part 3: Utilizing summer annual forage crops

Plan carefully for successfully producing and utilizing emergency summer annual forages.

Utilizing summer annuals

Summer pasture

Sudangrass and sorghum-sudangrass can provide supplemental summer pasture when cool-season grasses go dormant and the feed supply is short.

Sudangrass and pearl millet produce better pasture than sorghum-sudangrass because they are usually leafier. They also provide a more uniform supply of feed for grazing and support higher daily gains or milk production. Sorghum-sudangrasses produce higher yields, but are better used to support livestock on maintenance or lower productivity levels.

Graze the summer annual grasses in a short, rotational grazing system. Subdivide fields into three or more pastures so that each pasture can be grazed down in seven to 10 days. Stagger the date of planting each pasture by about 10 days so that grazing will begin on each pasture when growth is at the appropriate height. This rotation system allows maximum production of quality forage.

Graze sudangrass when it reaches 15-20 inches in height and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids when they are 18-24 inches tall. Danger from prussic acid poisoning will be low when grazing is delayed until grass is this tall. Graze down rapidly to 6 inches of stubble before moving livestock to a fresh pasture, and do not graze regrowth until 18 inches of growth accumulates. If growth is more than 36 inches tall, harvest as hay, green chop or silage since grazing cattle will trample and waste much of the forage. Regrowth will be more rapid following cutting this taller growth than if it is trampled.

Summer grazing lasts about two months. During this time, each acre of these pastures can provide feed for one to six mature dairy or beef animals. Grazing management and soil fertility and moisture will determine total production. Sudangrass, sorghum-sudangrass hybrids and forage sorghum pastures are not recommended for horses because kidney ailments may develop.

Green chop

Sorghum-sudangrasses are well-suited to a green chop program. Under a three-to-four cut system, the forages produce higher yields than other summer annual grasses. Begin chopping after the plant is 18 inches tall or cut at least 10 days after a killing frost to avoid prussic acid concerns. First cutting should be taken prior to heading.

Field losses are less from green chopping than from grazing or haying. However, the fast growth rate of sorghum-sudangrass results in variable amounts and quality of feed throughout the growing season. When grass is young and growing rapidly, it may contain 20 percent crude protein and produce a highly succulent feed. As the crop grows taller and nears maturity, the protein content may drop to 7 percent or less, and fibrous, low quality green chop is produced.

Nitrates can become a problem in a green chop program under certain growing conditions. Do not feed green chop that has heated in the wagon, feed bunk or stack, or that has been held overnight. Nitrates are converted to nitrites as plants respire; nitrites are about 10 times more toxic than nitrates.

Hay

For good quality hay, harvest sudans and sorghums before heads emerge or when they are 30-40 inches tall. These hays will contain slightly less protein than alfalfa hay and as much energy as good quality alfalfa hay. Sorghum-sudangrass hybrids are generally more difficult to make hay out of because of the larger stems. Crop should be cut 6 inches above the ground to encourage regrowth and two cuttings may be expected depending on yield

Silage

Forage sorghums should be harvested at the mid-dough stage for ensiling. At this point, quality is still good and most types have dried down enough for ensiling. Non-heading types usually require a killing frost for the plant to get dry enough to ensile. This can be a problem in that lodging and leaf loss (therefore quality) may occur during the drying period after frost

Seedbed preparation

A firm, well-prepared seed bed is needed for good seed-soil contact and rapid germination. Conventional, minimum or no-till drilling can be used for establishment.

Seeding date

Sudangrass and sorghum are warm-season grasses. Seed should be planted into soils when average soil temperature is above 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Plan the seeding date to produce desirable feed when needed. Stagger planting dates to aid rotational grazing. It takes at least six weeks after planting before usable forage is available. Later plantings will result in lower yields due to summer droughts and fall frosts.

Planting rates

Recommended planting rates depend on row spacing. Broadcast and narrow-row spacing are preferred for sudangrass and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids because they result in shorter plants with finer stems. Total forage yield will be similar for different row spacing because sorghums and sudangrasses tiller. Removing the primary growing point at the first cutting enhances tillering. First-cut yields are usually higher for broadcast or narrow-row seedings than for 20-40-inch rows.

If planting with a grain drill, plant 15 to 20 pounds per acre seed of pearl, German, Japanese or Siberian millet. Forage sorghums should be planted at 12-15 pounds per acre with a grain drill. Use 6-12 pounds per acre for pearl millet. Sudangrass and sorghum-sudangrass are seeded at 20-30 pounds per acre in 7-inch rows with a grain drill. Higher seeding rates help in producing finer stems, which is desirable for grazing and hay.

Planting depth

Seed to a depth of 1-2 inches, depending on soil moisture conditions. Seeds planted too deep do not emerge well and poor stands may result.

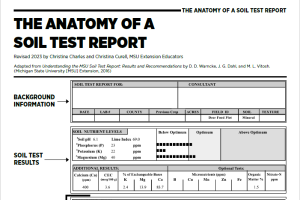

Fertilization

Summer annual grasses have fertilizer requirements similar to those of corn. With rapid growth, apply sufficient nitrogen at planting to ensure establishment and high first-cutting or grazing yields. Apply 40-80 pounds of nitrogen per acre at planting and an additional 50 pounds after the first cutting or grazing. Phosphorus and potassium should be applied based upon soil test recommendations.

Prussic acid poisoning

Cellular damage to sorghums and sudangrasses from frost, wilting, bruising, drought, excessive soil nitrogen or deficiencies in soil phosphorus or potassium can result in prussic acid poisoning in cattle. Prussic acid poisoning consists of the following sequence of events: plant cells rupture and cyanic acid (HCN) forms from cyanogenic glycosides; cattle consume forage with elevated HCN levels; HCN is absorbed from the rumen; HCN binds to hemoglobin; asphyxiation and death occur.

Poisoning is most likely after a frost when animals consume the leafy regrowth. Regardless of season, plants less than 18-24 inches tall should not be grazed. Suspect forage should be harvested as dry hay or silage. Both harvest methods tend to reduce hydrocyanic acid levels.

Nitrate poisoning

High dietary nitrate levels can overload the animal’s ability to detoxify this chemical and can result in death due to asphyxiation. In the rumen, nitrate is reduced to ammonia, which is absorbed into the bloodstream or converted into microbial protein. High dietary nitrate levels that overload this microbial reduction system cause an accumulation of nitrite in the rumen. This nitrite is then absorbed into the bloodstream where it binds to hemoglobin in place of oxygen. This deprives the tissues of oxygen and causes abortions and asphyxiation.

Sorghums and sudangrasses can accumulate high levels of nitrate during environmental conditions that decrease plant growth rate, including water stress, lack of sunshine and high nitrogen fertilization. Plants usually absorb nitrogen as nitrates and synthesize protein. However, during stress, the synthesis rates decrease and nitrates accumulate. Cattle should not be fed forages with nitrate levels greater than 2 percent. Nitrate analysis can be obtained from numerous commercial laboratories.

Contact your local Michigan State University Extension field crop educator for more detail on emergency annual forages in your area.

Part 1 of this series covers sudangrass, sorghum and hybrids. Part 2 covers millets.

Content of this series of articles is based on a previous article by retired MSU Extension state forage specialist Rich Leep.

Print

Print Email

Email