GMOs: A surrogate for the debate about agriculture?

Perceptions of the agricultural and food industries, trends in higher education, questions around research funding, political leanings and socioeconomic factors can also play a part in public concern over GMOs.

Public concern over genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, is often associated with questions over their possible effects on human health and their environmental implications. However, perceptions of the agricultural and food industries, trends in higher education, questions around how research is funded, political leanings and socioeconomic factors can also play a part.

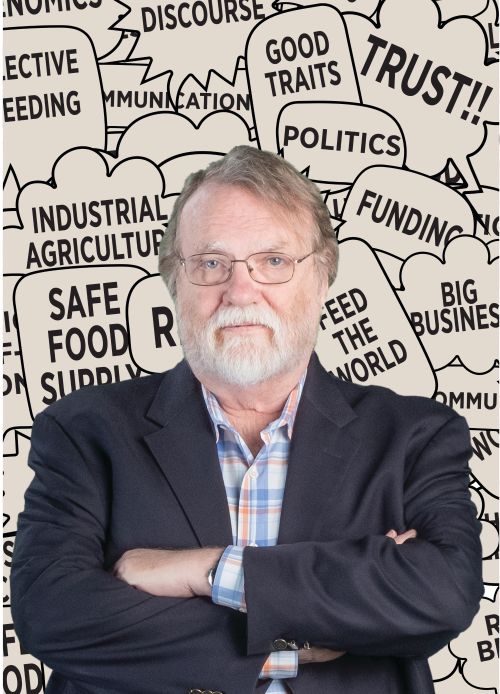

Paul Thompson, holder of the W. K. Kellogg Chair in Agricultural Food and Community Ethics at Michigan State University (MSU), conducts research on the ethical and philosophical questions associated with agriculture and food.

“The debate over GMOs sits in a kind of strange space,” said Thompson, a professor in both the colleges of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), and of Arts and Letters (CAL). “There is a sense in which people learn about some pretty standard practices in agriculture through the GMO debate.”

One such example is plant breeding. For thousands of years, Thompson pointed out, people have been selectively breeding plants and manipulating seeds to produce traits we find most desirable. That’s genetic modification, but many don’t view it as such.

“There’s a kind of disconnect in terms of the way people think about agriculture, in the way they think about their food and their environment,” said Thompson, who has dual appointments in the departments of Community Sustainability; Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics in CANR; and Philosophy in CAL. “I think there are issues ahead in terms of how we negotiate some of these things.”

MSU alumna Elizabeth P. Ransom agrees with Thompson about the complexity of public concern surrounding GMOs. Ransom is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Richmond and has research interests in the sociology of agriculture and food.

Ransom believes there needs to be more transparency in regards to GMOs —which universities and researchers could help provide to those who want to learn more about the benefits as well as the issues. The intersection of food and social issues creates an opportunity for discourse on these complex topics.

“There are going to be some unintended consequences [with GMOs]. How do we review and monitor those?” she asked. “There’s a real opportunity for universities, but it does require scientists in academia to be a little more reflective [in helping the public learn about the benefits and issues related to GMOs].”

Public perceptions

Public perceptions and opinions about GMOs aren’t based solely on facts, and can be informed by their assumptions and emotions. Political beliefs, gender, education levels, and socioeconomic factors also influence beliefs and behavior.

While the correlation between education levels and GMO perceptions seems to be weakening, political leanings are starting to have some influence, said Thompson.

“Liberals tend to be more worried about GMOs, and don’t trust the science on GMOs,” he said. “Conservatives don’t trust the science on climate change.”

The way different groups approach and interpret risk can also factor into what they think about GMOs.

“There are socioeconomic and gender factors in how people think about risk in general. People who are traditionally marginalized tend to be more concerned. If there’s an indication something might be risky, they assume it is,” he explained. “Men are less likely [than women] to infer risk on the basis of some sort of initial indication.”

There is also public concern around GMOs and other issues, in part, because there isn’t a regulatory mechanism in the United States for blocking something based on social impact, according to Leland Glenna of Pennsylvania State University (PSU).

Glenna is a professor of rural sociology and science, technology, and society in the PSU College of Agricultural Sciences. For the past 15 years, he has studied agricultural biotechnology, genetically engineered, or GE, crops and their social impact, including the ethical implications of democratizing science and technology research.

Many people are concerned about concentration and consolidation within the agriculture and food industries and view GMOs as facilitating that trend. Funding from industry for university research is another concern.

“People are losing trust in this science because there’s too much industry involvement,” Glenna said.

Additionally, the growing inequity and economic issues in the United States have caused ripple effects on what people say and what they actually do, said Ransom.

“I think we have to actively start reducing some inequalities,” she said. “We have to rethink our education system. If you don’t have a public that can better understand nuances, then they will not be able to discuss and debate the issues surrounding the introduction of new technologies.”

Food safety is an integral part of the GMO conversation, especially for the public. Thompson said people tend to make broad generalizations about food that lead to specific actions. Some of those actions may also be attributed to a lack of trust in food industries and industrial agriculture.

“For a person who’s not involved in the food system professionally, that starts to mean: ‘Well, I’m going to start eating more salads,’ or ‘I’m going to start buying organic,’” said Thompson. “I think there is a widespread perception that these food industry firms are not ethically responsible firms.”

Marketing plays a role, too.

“The food companies themselves have sort of encouraged the idea that all of the products we’re buying were produced in pristine little family operations where it’s perennially springtime,” said Thompson. “I don’t think anyone believes all of the marketing, but it does have an effect.”

Agriculture & food systems

Since starting his career in 1980, Thompson has seen a significant amount of industrialization, resulting in the loss of family farms, as overall agriculture and equipment has grown larger. It was the ’90s when he first started hearing the term “industrial agriculture.”

“Every aspect of the food system has become more and more concentrated,” he said. “I would actually love to see a food system where we would have more people who are actually farmers. There are things that would be healthy in so many ways about that.”

Agriculture has moved more into genomics and biotechnology, where a lot of the knowledge is proprietary and not published.

“We do see a whole host of changes that are at least ethically controversial,” he added.

Proponents say GMOs increase the efficiency of agriculture and provide new ways to feed the world. But some argue, as Glenna does, that the science hasn’t lived up to all its promises.

“We were going to have all kinds of nutritional outcomes, and it just hasn’t happened,” he said.

The global conversation expands to the overall effects of GMOs and agriculture on the environment, biodiversity and sustainability.

“In some respects it’s the extent of agriculture that is a difficult issue, especially as you start to think on a global basis,” said Thompson. “One of the things we have to think about is: How much of the earth’s surface do we really want to dedicate to agriculture, and should we be setting aside areas?”

With her background in sociology and anthropology at the University of Richmond, Ransom expressed concern about the effect of genetically engineered crops on smallholder farms globally and how that ties into a larger debate about sustainability.

“Our global food system is pretty diverse still,” she said. “From a sustainability point of view, smallholders have been overlooked.”

When smallholder farms do well, they could produce more food on smaller parcels of land than industrial farms that often focus on one type of crop, said Ransom.

Her ongoing research focuses on global trade and international agriculture assistance in developing countries. Specifically, she studies the ways agricultural assistance targets women, including within the dairy chain in Africa.

GE crops can help and harm smallholder agriculture, she said. “That’s the challenge for GE scientists. They really need to be nimbler about how they work in diverse spaces.

“Our world has increasingly become more urban. As we grow as a population, are there ways we can grow and retain rural livelihoods?”

The role of universities

While land-grant universities were enthusiastic about GMOs early on, they failed to understand the broader implications for large public institutions, such as funding shifts to increased reliance on grants and industry.

“As a result, the land grants really did lose a fair amount of their credibility and have really struggled to recover it,” Thompson explained. “It’s actually created some divisions within the ag programs that are really unfortunate.”

Historically, agricultural schools developed seed varieties for commercial use. Increasing regulations and expenses, especially related to developing GE seeds using biotechnology, have made it much harder for universities to compete in this area.

“It’s really reduced the role that nonprofit actors can play in the food industry,” Thompson added. “It’s weakened the commitment of public institutions to developing technology in the food system.”

Thompson said that communications, reflection and outreach are becoming a more structured part of the research process, and scientists should take some cues from the Extension outreach programs at land-grant universities like MSU.

“It’s becoming a responsibility for people who want to work in these fields to actually design and support research, education and outreach programs,” he said. “These programs can really start to repair this loss of trust and confidence.”

Scientists and researchers are being challenged to communicate in ways that are easier for the public to understand, said Ransom.

“I think scientists are sometimes quick to dismiss the public’s concerns,” she said. “University scientists historically have been a source people could trust. I think that the universities have to work hard to communicate the work they do and keep instilling trust.”

MSU is engaging in community conversations through its Our Table discussions that are focused on food, where it comes from and how it affects human health and the environment. Panel discussions to date have focused on food access, food waste and food safety. An Our Table on GMOs is planned for this fall. Learn more at food.msu.edu.

This article was published in Futures, a magazine produced twice per year by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. To view past issues of Futures, visit www.futuresmagazine.msu.edu. For more information, email Holly Whetstone, editor, at whetst11@msu.edu or call 517-355-0123.

Print

Print Email

Email