I need Silage. Is it ready yet?

How can farms bridge the gap to the newly available corn silage when inventories run out?

As the familiar sights of choppers in the fields and trucks hauling silage down the roads return, some farms face a recurring challenge. This challenge revolves around managing the continual demand for corn silage when inventories are running low or are no longer sufficient. This situation is often answered by purchasing additional loads of silage to either complement or substitute the source of corn silage in the rations. The goal is to outsource while we bridge the gap until new corn silage becomes available after ensiling. However, a pressing question that occurs with farms in this situation is: When is the new silage ready for feeding? The question is often answered by “I need it now.”

In a previous article, we delved into some of the intricacies of the fermentation process. It's crucial to remember that all phases of this process are necessary to preserve the quality and increase the availability of the nutrients in silage. On average this initial process takes 21 days. At that point, the new corn silage is expected to stabilize and become ready for feeding. Recent data from Michigan State University supports that digestibility may continue to improve beyond 41 days after ensiling, pointing to the traditional advice to allow for two months of fermentation before feeding if possible. This ideal scenario is not the focus of this article; here we’ll focus on what dairy farmers can do when they don't even have 21 days worth of old-crop silage on hand.

First, it is important to remember that changing forage sources is never advisable without a proper transition. An abrupt change can be detrimental for the stability of the rumen environment. Each forage change should be blended into the ration to allow the rumen the time to adapt to the nutritional profile of the new feed source. Thus, our initial recommendation is to continue outsourcing corn silage for some weeks after new silage is harvested, when possible, but if you want to decrease your bill for outsourced feed you can use the 21 days as the transition to the new source of corn silage.

The following template for a potential transition plan is meant to be used as an example. For farm-specific situations it is encouraged to consult the farm’s nutritionist and MSU Extension experts.

Harvest Days

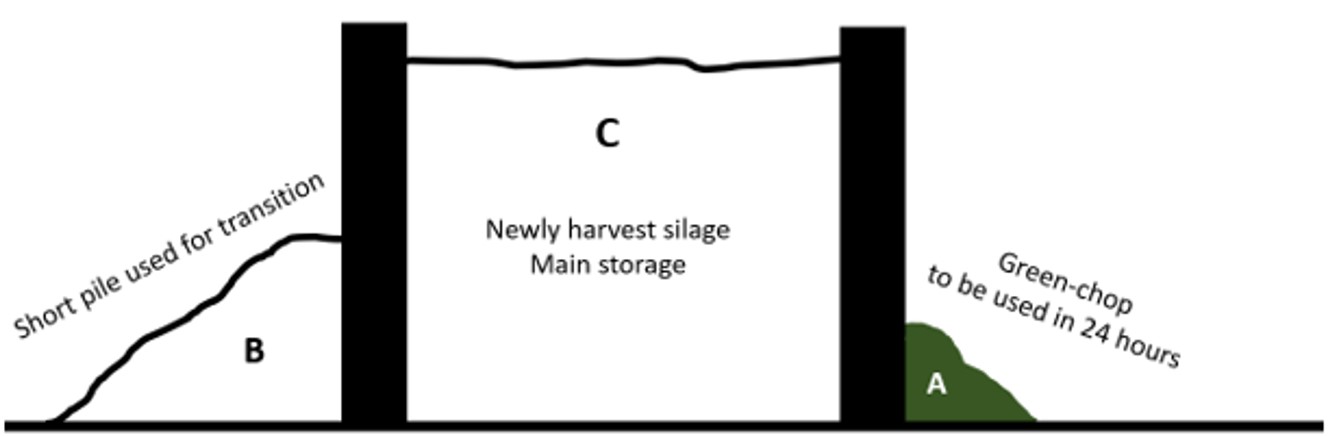

While corn harvest is ongoing the farm has the option to use green chop to complement the purchased silage. For this to be done optimally, trucks should deliver from the field every day and the delivered amount should be fed in less than 24 hours. When doing this, be aware that green chop may impact digestibility and should be tested daily for moisture content prior to inclusion. If the plant used for green chop was stressed by drought conditions, also be advised that nitrates can become an issue. The only way to positively know if there is excessive nitrates is to have the corn silage tested for nitrates. Thus, monitoring is recommended. Blending green chop and your current source of corn silage can occur during the duration of silage harvest. Now, what can be done for the days between harvest and when the new pile has finished the optimal fermentation process?

Figure 1: Potential layout for the multiple locations where trucks can deliver silage.

Post Harvest

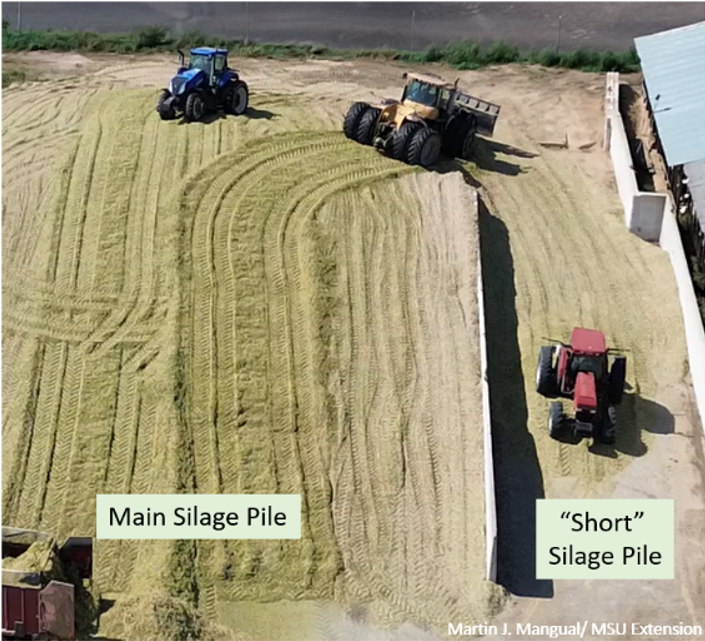

MSU Extension recommends creating a separate short pile of newly harvested silage, established on day one of silage harvest. The goal is to pack and cover a pile of silage that contains enough inventory to support 2-3 weeks of feeding. This short pile is to be kept separate from your main silage pile (see image 2). After silage harvest is completed this short pile should become the source of silage to be blended with your outsourced forage. Using this pile allows the bulk of your harvested new crop to ferment adequately and complete this process undisturbed by oxygen. Don’t forget that the fermentation process is incomplete, thus digestibility, acid profile and even nutritional composition is expected to be different than fully fermented corn silage. Therefore, plan with your nutritionist to ensure rations are adjusted accordingly.

Example of a short silage pile

After the fermentation process is completed in the main pile, it can be tested and be used as the main source of silage. Ideally, use the left over from the short pile to blend with the new forage source until it runs out.

In addition to managing the current shortage, it's crucial to maintain records and analyze the factors contributing to silage inventory shortfalls. Meet with your agronomist, herd nutritionist and MSU Extension expert to develop strategies for addressing and preventing such situations in the future. Options may include ration adjustments and different hybrid selection for the next year, among others.

In conclusion, managing corn silage shortages during harvest season is a critical task. Careful planning and a gradual transition process are key to ensuring a stable supply of high-quality silage for your valuable dairy herd. By following a well-structured transition plan and analyzing the specific factors impacting your dairy farm, you can better prepare for future harvest seasons and maintain the health and productivity of your herd. For more information, questions, or regarding your dairy farm's situation, contact Martin Mangual, MSU Extension, at carrasq1@msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email