Industry concerns with liver abscesses in finishing cattle

Liver abscesses increase costs with reduced efficiency of production and increased liver condemnation.

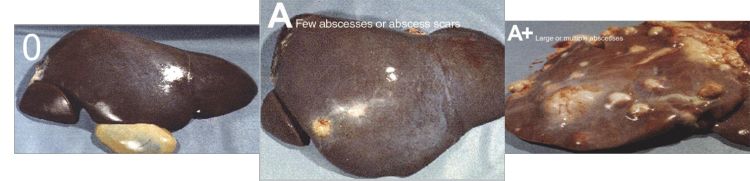

The United States beef industry has a renewed interest in trying to understand what causes the development of liver abscesses in cattle and their subsequent effect on the growth performance of cattle raised for beef. In a recent issue of the Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice journal, liver abscesses in cattle were reviewed. Liver abscesses are not a new problem for the beef industry and have been associated with feeding cattle primarily grain-based diets dating back to the 1930’s. Liver abscess prevalence rate varies considerably by region, presumably due to different feedstuffs fed, different feed management, and different cattle types (e.g., beef steers and heifers, beef x dairy steers and heifers, dairy steers, cull beef cows, cull dairy cows). Cattle livers containing abscesses are condemned at slaughter and represent an economic loss to the U.S. beef industry of approximately $61.2 million a year (25.5 million fed cattle, 30% liver abscess rate, $8 per liver), not including reduced carcass weight from the additional trimming required, reduced marbling deposition, and reduced feedlot performance. For many cattle producers, the effect of reduced feedlot performance caused by liver abscesses goes unnoticed and is only discovered at the time of slaughter. Severe liver abscesses (i.e., livers containing multiple smaller abscesses or larger abscesses) have been associated with a 5% reduction in average daily gain for feedlot cattle.

Liver abscesses have long been associated with feeding cattle diets with large amounts of fermentable carbohydrates (i.e., grains). Digestive upsets that result from the fermentation of readily fermentable carbohydrates are in response to a subsequent decline in rumen pH. Cattle consuming a forage diet typically have a rumen pH just under 7 or neutral, and cattle consuming a concentrate-based diet, typical of finishing beef cattle, may have an average rumen pH just above 6. Fermentation of feed in the rumen produces volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which are absorbed and used for energy, and lactic acid, but these acids cause the rumen pH to decrease. When the rumen pH remains below 5.8 or 5.6 for an extended period of time, the condition is called subacute ruminal acidosis, and the more severe case, when the pH is less than 5.2, is called acute acidosis. Low rumen pH can insult the epithelia cells lining the rumen and compromise barrier function to cause rumenitis and inflammation. It has been believed that the low rumen pH causing rumen barrier disfunction may allow bacteria access into the portal blood stream and thereby access the liver. Recently, it is being speculated that compromised gut barrier function in the small and (or) large intestine may be another route for bacteria to infiltrate into the blood stream and for bacteria to colonize in the liver to form liver abscesses. Abrasive objects, such as hair consumed from grooming and/or splinters from wood chewing, can be irritants to the rumen epithelium as well.

Because liver abscesses are commonly associated with ruminal acidosis, increasing the roughage content of the diet can stimulate salvia production during rumination, resulting in a buffering effect of ruminal pH decline. As a likely result, increasing the roughage concentration in the diet has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of liver abscesses in feedlot cattle. Examples include increasing chopped/ground alfalfa hay from 10 to 30% of the diet resulting in a reduced liver abscess prevalence of 15 to 2%; increasing corn silage concentration from 0 to 15% resulting in a reduced liver abscess prevalence of 29 to 15%; increasing corn silage concentration from 15 to 45% resulting in a reduced liver abscess prevalence of 35 to 12%. However, there are other instances where research has failed to detect a reduction in liver abscess prevalence due to increasing dietary roughage inclusion. For example, research published in the Journal of Animal Science reported increasing chopped grass hay from 8% to 16% of the diet did not reduce the incidence of liver abscesses but increasing the chop length of hay from 1 to 3 inches reduced liver abscess prevalence from 12.5 to 0%. Increasing the physical effectiveness of the roughage in the diet increases chewing, rumination time, and saliva production to help buffer the rumen pH. Roughage inclusion can also increase passage rate of digesta, therefore reducing the acid load experienced in the rumen over an extended period of time. Therefore, determining the balance needed between grain and effective forage in concentrate-based finishing diets is needed for maximum growth performance and animal health. Other feed management practices that regulate feed intake

Tylosin-phosphate is the most commonly used antibiotic feed additive approved for controlling liver abscesses in feedlot cattle. There are other antibiotics approved for controlling liver abscesses in feedlot cattle, such as chlortetracycline, virginiamycin, and bacitracin methylene disalicylate. If you are considering feeding any of these products to reduce the incidence of liver abscesses in your feedlot cattle, speak with your veterinarian to get antibiotic use approval and develop a plan for feeding medicated feed. Ionophores and essential oils with antibacterial properties have shown less conclusive evidence of consistently reducing liver abscesses in feedlot cattle. In the future, vaccines for preventing liver abscesses may become commercially available as research continues to improve their efficacy.

If you have concerns with liver abscesses in your cattle or would like to discuss this topic further, reach out to myself or one of the other Michigan State University Extension Beef Team members. We would be happy to talk to you about your nutrition program and help develop a plan to control potential nutritive disorders from happening and allow your cattle to meet their optimal potential.

This article originally appeared in the Michigan Cattleman’s Magazine.

Print

Print Email

Email