James Kelly: A masterful bean breeder and mentor

MSU University Distinguished Professor James Kelly has developed 47 bean varieties in the past 35 years. And he's not finished yet.

Halfway around the world at a gala reception in Africa, Michigan State University (MSU) Distinguished Professor James Kelly mingles as if right at home. He works his way from one candlelit table to the next, taking only a few steps between conversations. Most centered on beans and bean research. In addition to knowing many of the guests, Kelly has close personal ties to several of the evening’s distinguished awardees, including a few former students.

Having developed 47 bean varieties in the past 35 years, Kelly was frequently recognized and fondly greeted, not only at the evening’s festivities, but throughout the weeklong 2016 Joint Pan-African Grain Legume and World Cowpea Conference in Livingstone, Zambia held in early March. He could easily chalk up the notoriety and camaraderie to an illustrious career, but chooses not to.

“Maybe it’s just a case of longevity and having been at this long enough,” he said. “Having worked with the crop for that many years, both as a student and then as a researcher in a couple of different places and so forth – you build up these friendships and relationships with people. Yeah, I think just because of that and my work being published over the years. People see the publications and they talk to you and so forth.”

Kelly, who speaks with a charming Irish accent, was born and raised in County Antrim in the northeastern part of Northern Ireland. Growing up, he spent time on his grandfather’s livestock farm, but it was his father’s interest in horticulture that had the most influence on Kelly’s career. His dad, a primary school teacher by trade, grew vegetables in greenhouses at their home. Frequent visits from the local Extension specialist who offered valuable plant advice made a lasting impression on the young lad, who eventually realized that science was what intrigued him most.

While working on a bachelor’s degree in agriculture in his homeland, Kelly began to take note of Norman Borlaug who at the time was making headlines plant breeding, mainly wheat, and who later became known as the “Father of the Green Revolution.” Inspired by Borlaug’s achievements, Kelly came to the United States in 1969 to pursue his doctoral degree in plant breeding from the University of Wisconsin (UW). As part of his doctoral studies, Kelly spent about two years conducting research overseas for the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). It was then that his bean breeding connections began to firmly take root.

“Yeah, there are a lot of tentacles, I suppose,” he said, describing his relationships within the bean community both at home and across the globe.

Upon receiving his Ph.D., Kelly became employed by UW and has been working with beans ever since. He joined the MSU faculty in 1980 as an assistant professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, now Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences.

While developing one bean variety can take more than 10 years, Kelly said he stays interested in the process by setting a series of short-term goals. Along the way, he works closely with farmers and the processing industry to ensure that they are pleased with the final product. When asked which of the bean varieties he considers to be his crowning achievement, Kelly said it was probably his first – a navy bean called C-20. Although not on the market for long, C-20 became “grandpappy” to many black bean and navy bean descendants, he said.

“C-20 had its faults, but we were able to learn from those and improve future cultivars — which is what you do in plant breeding,” he said. “You develop something and then you build to improve it further. Even when you have new varieties coming out, we still have a couple years of work on them to improve them further.”

Samurai, released in 2015, is Kelly’s most recent creation, made specifically for the Japanese market. Although it resembles a white bean used in baked beans, Samurai is processed into a bean paste used in many Japanese baked goods and sweets. Kelly said that because the country is heavily populated and has little available land mass, it must depend on other countries for many of its agricultural products.

The majority of Kelly’s beans are grown in North America, primarily Michigan, Minnesota and North Dakota. Kelly said there are huge challenges to bean production, from high plant costs to production on primarily marginal lands. Because of limited investment in research, bean yield improvements have failed to match those of several major cereal crops. The fact that pulses are much more complex nutritionally makes improvements more difficult to achieve.

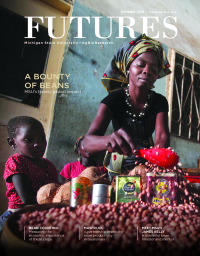

Beans are key contributors to the food security of many countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, where they have become integral components of smallholder farming systems. Kelly has forged research and outreach partnerships in countries such as Mexico, Ecuador and Rwanda in efforts to increase both the quantity of beans produced per unit of cropland and their nutritional quality.

When people hear the word “breeding,” Kelly said they often erroneously assume it involves GMOs. In fact, dry beans are not a GMO crop. Part of the reason, he said, is that scientists have not been able to genetically engineer beans.

“Would there be GMO traits out there that would help beans? I’m certain there would be,” he said. “Are they going to come? I don’t know. There is nervousness about trying to bring them forth and trying to sell them. One feels sometimes like you’re running a race against other commodities with your hands tied behind your back because those tools are not available to you.”

Kelly admits that the fact that beans do not contain GMOs makes marketing beans easier. However, with mandatory food labeling expected in the near future, baked beans could be labeled GMO because they contain sugar, a GMO crop. Either way, Kelly said he is irritated by the GMO backlash because engineered traits such as disease resistance, insect resistance and herbicide resistance can help decrease dependency on chemical use and save resources – both economically for farmers and ecologically, especially in developing countries.

“Third-world farmers are being prevented from access to these food crops by essentially people who are well-fed and well-healed. That’s what bothers me the most,” he said. “Why should they have a right to dictate what others, who have much less in the way of resources, do?”

As bean breeding begins to incorporate more and more plant genomics – an area Kelly is not trained in – he is carefully thinking about his future.

“Somebody just asked me if there was anything I wanted to finish before retiring,” he said. “The thing with plant breeding, there is always something you want to move forward on. You’d like to see some things click and work, but there isn’t anything specifically. I’m not hanging on here to get one thing finished. I’ll find an appropriate time to retire.”

In the meantime, Kelly remains deeply committed to both his research and his teaching. Mentoring and training of students has been an integral component of his research strategy across his entire career.

More than 30 graduate students, many from developing countries and many who did their research in the developing world, have obtained M.S. and Ph.D. degrees under his guiding influence. More than 100 other students have sought and benefitted from his advice as a member of their graduate committees. Kelly continues to teach in the classroom, too, helping to equip new generations of agricultural talent. And just last summer he graduated six graduate students under his advisement.

“I try to instill in my students that one has a job to do, and that’s it,” he said. “You need to put in the effort, get the work done and do it right – taking it through to the final dissertation and getting the information published. Some of the work is a lot easier than others.”

This article was published in Futures, a magazine produced twice per year by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. To view past issues of Futures, visit www.futuresmagazine.msu.edu. For more information, email Holly Whetstone, editor, at whetst11@msu.edu or call 517-355-0123.

Print

Print Email

Email