For more than 160 years, Michigan State University (MSU) has been dedicated to a land-grant mission that emphasizes teaching, research and outreach. John A. Hannah, the 12th president of MSU who occupied the role from 1941 to 1969, was a steadfast believer in that model.

A 1923 graduate of the university, Hannah promptly netted a position with MSU Extension as a poultry specialist after receiving his degree. He served in that job for a decade until becoming the managing director of the National Poultry Breeders and Hatchery Committee.

Although not an employee of MSU, he remained in close contact with the university. After just one year, Hannah returned to accept the post of secretary of the State Board of Agriculture, the governing body of the university at that time. He remained in the position until assuming the MSU presidency.

Hannah’s tenure as president is widely recognized as a period of tremendous growth for MSU. He headed initiatives to attract more students and faculty, implement innovative curriculum changes and extend the university’s global reach.

A chief accomplishment of Hannah’s was driven by his desire to spread the land-grant philosophy to areas where it could be most effective. Africa was a natural destination, encouraged by Hannah’s close friendship with Nnamdi Azikiwe, who would later become the first president of Nigeria.

As premier of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, Azikiwe steered efforts to establish a new university in the country. In 1958, with assistance from various organizations, Nigerian leaders came together with scholars from the United Kingdom and the U.S., including Hannah.

The group drafted a white paper that outlined the challenges facing Nigeria and how a land-grant university could address them. An agreement was reached to open the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1960 – the first land-grant university in Africa and a bastion of knowledge for the region.

Since then, MSU has further formalized its relationship with countries across the African continent. Research has expanded on the ground, and students from a variety of countries are attending MSU.

In 2016, more than 330 MSU undergraduate and graduate students were from Africa, according to the MSU Office for International Students and Scholars.

Today, Hannah’s legacy of cooperation with Africa carries on stronger than ever.

A global leader in international development

The founding of a new university is a colossal undertaking, and curriculum and program creation are an essential aspect of the startup process. For the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, faculty members in the MSU Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) played a pivotal part.

Among other contributions, AFRE professors Carl Eicher, Glenn Johnson, Carl Liedholm and Warren Vincent helped to establish an economic development institute at the university.

From the beginning of the MSU-Africa partnership, AFRE has led the way. Currently, AFRE continues to hold the majority of the MSU research portfolio in Africa – and for good reason. The Center for World University Rankings named AFRE the fourth-best program in the world in 2017 for excellence in the agricultural and applied economics fields.

“Much of MSU’s involvement in Africa is economic in nature, so it makes sense that AFRE is heavily featured,” said Titus Awokuse, the AFRE chairperson. “The key to success in international development work is having a foundation of long-term relationships, and that’s what we have in AFRE.

“At MSU, we don’t just fly in and out. In addition to short-term visits by faculty and students, we also have people stationed long term in African countries who are doing research and constantly working with the people there to build local skills and capacity. People see us all the time, and that’s important to establishing trust and credibility.”

AFRE is awarded grants from a diverse swath of funding entities to engage with dozens of countries, but a significant number of projects funnel through the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP).

The Food Security Group at MSU is an integral partner in FSP and is composed of several AFRE faculty members. FSP is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and is one of 24 labs supporting the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future global hunger and food security initiative.

FSP operates in eight countries in Africa – Burundi, Malawi, Mali, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia – and two in Asia.

The mission of FSP is to promote inclusive agrifood system productivity growth, improved nutritional outcomes and enhanced livelihood resilience through improved policy environments.

Helping to draft new agricultural policy in developing countries is one of AFRE’s major focuses. For example, AFRE assistant professor Saweda Liverpool-Tasie is the principal investigator on a $12.5 million FSP project that seeks to build internal capacity for Nigeria to perform evidence-based policy analysis.

Helping to draft new agricultural policy in developing countries is one of AFRE’s major focuses. For example, AFRE assistant professor Saweda Liverpool-Tasie is the principal investigator on a $12.5 million FSP project that seeks to build internal capacity for Nigeria to perform evidence-based policy analysis.

Although Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa, with a GDP of $569 million, and has an estimated population of 187 million, it is among the poorest developing nations with a per capita income of $2,700.

Liverpool-Tasie and her colleagues are training a broad group of stakeholders, particularly faculty and students at Nigerian universities and research institutes. Training and informational workshops are also offered to Ministry of Agriculture staff.

This will bolster the country’s ability to participate in informed policy dialogue that ideally generates an outcome benefiting its citizens. The project, which partners with the International Food Policy Research Institute, began in July 2015 and runs through June 2020.

Outside of FSP, AFRE receives funding from nongovernmental sources and foundations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Awokuse believes that these collaborations are vital to AFRE’s future.

“Our goal is to build on our relationships with governmental organizations, USAID and others, but we must also be nimble and responsive to changing funding environments,” Awokuse said. “That will mean diversifying our funding lines and strengthening bonds with all of our partners.”

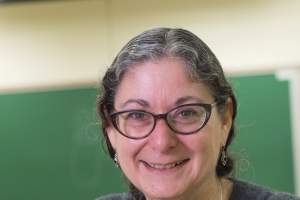

In his professional life as AFRE chairperson, Awokuse is tasked with examining the horizon to position the department for lasting success. But there is a personal angle to international development for him – especially in Africa. He doesn’t speak of poverty and food insecurity in theoretical terms. He lived it.

“Part of my interest in these activities is because I’m an applied economist, but I also experienced the negative effects of poverty as a young man who grew up in Nigeria,” Awokuse said. “My family and other people I knew were facing the same problems we’re looking at today. I realize that the work of others helped to put me in the position that I am now, so this is a way for me to give back.

“In AFRE, we’re helping to feed the world. We’re helping to reduce poverty. These are things in which we should take great satisfaction.”

Bringing knowledge home

In Ghana, a country on the West African coast that supplies 90 percent of its own food, more than half of the labor force is employed within agriculture.

White yam is the nation’s primary food security crop. Only Nigeria produces a greater volume of the tubers. In total, more than 90 percent of all white yam around the world is from West Africa.

Cultivating the crop is a laborious endeavor, as most farmers utilize traditional agriculture methods.

White yams develop from smaller seed yams that are planted on mounds. Stakes are placed beside the mounds in order for the yam vines to grow up and around them.

For many farmers, the exhausting effort is justified by the reward. White yam fetches a high return at local markets.

Prized for their sweet taste and rich nutrient content, white yams are often prepared by peeling, cooking and cutting into small pieces for inclusion in stews – alongside vegetables and meats. Pounding boiled yams with a mortar and pestle is another popular treatment, which creates a paste-like texture that is torn apart and eaten in soups with other ingredients.

Discovering ways to improve the growing process of white yams is especially important to Eric Owusu Danquah, a native Ghanaian and doctoral student in the MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences.

“It’s important for farmers in Africa to start looking at ways to scale up yam production to medium- and large-scale operations,” Owusu Danquah said. “Most farming is currently very small in scale, and the technology being used is not the most efficient. Through my research, I hope to show farmers that adopting new strategies can improve their yields.”

Owusu Danquah is principally interested in the impact of climate change on soil fertility and the ways it affects sustainable food production. He’s always been cognizant of the importance of agriculture, a notion instilled by his father.

Owusu Danquah is from Ofoase Kokoben in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. His father, a retired teacher, partakes in farming, so agriculture was never too far from the family’s consciousness.

“As the eldest of my siblings, I always followed my father in the fields,” Owusu Danquah said. “I gained a lot of experience with practical, hands-on agriculture. That got me interested in learning more about general agriculture, as well as other sciences.”

In junior and senior high school, Owusu Danquah excelled. As his curiosity in science blossomed, the accolades followed. Honors included agriscience student of the year and overall student of the year.

Armed with his newfound knowledge, he entered his undergraduate program in natural resources management at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana. He concentrated on the big picture.

“I’ve long understood that our natural resources on this planet are precious,” Owusu Danquah said. “If we want to continue human development while also reducing inequality, we must treat our natural resources with respect. Giving people the tools to help themselves in a sustainable way has been my goal.”

Owusu Danquah then earned a master’s degree in agroforestry from the university, where he served as a teaching and research assistant, and spoke with mentors about potential career paths. He opted to join the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’s (CSIR) Crop Research Institute in Ghana in 2011.

Under the mentorship of CSIR Crop Research Institute director Stella Ama Ennin, Owusu Danquah has focused on agronomy – research that promotes policy development and examines the viability of new technology to improve smallholder farmers’ livelihoods.

Eager to pursue a doctoral program while maintaining his position at CSIR, Owusu Danquah applied to the Borlaug Higher Education for Agricultural Research and Development (BHEARD) program in 2015. He was instructed to narrow his choice to three universities: two in the U.S. and one in Africa.

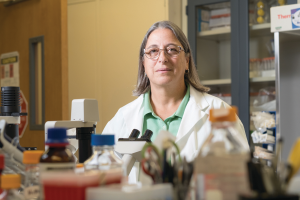

Meanwhile, Owusu Danquah began conversing with Cholani Weebadde, an assistant professor in the MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences. A plant breeder, Weebadde was keen on engaging with researchers who worked with white yam. Speaking with Owusu Danquah, the ideas flowed freely.

“Talking with Eric was perfect timing because I was interested in white yam, particularly field work that we can’t do in Michigan,” Weebadde said. “He’s done so much with white yam, and I wanted to tap into his experience. We worked with CSIR and BHEARD to come up with a Ph.D. program that was advantageous to all parties. Eric could further his research at MSU and take that knowledge home, and my program could gain access to a crop we’ve never studied before.”

After choosing MSU, Owusu Danquah arrived on campus in August 2016. BHEARD students traditionally perform only their final year of research in their home country, but given that Owusu Danquah is working with white yam, his field trials needed to take place in Ghana.

He required additional funding to support more trips to Africa. His MSU research team applied for and was awarded a grant from the Alliance for African Partnership, an MSU initiative that brings together partners inside and outside of Africa to look at new ways of addressing emerging challenges facing the continent.

Weebadde has urged Owusu Danquah to make as many connections as possible to build his network of colleagues. This has resulted in collaborations with MSU researchers such as David Kramer, a John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor of photosynthesis and bioenergetics.

Kramer’s technology PhotosynQ, which involves a handheld device that takes measurements of a plant’s photosynthetic efficiency and uploads the results to a publicly accessible database, has changed the way Owusu Danquah operates in the field.

PhotosynQ is just one of the technologies integrated into Owusu Danquah’s research. His CSIR research group has brought mechanized ridging to yam farming, replacing the labor-intensive mound method.

Owusu Danquah is also introducing pigeon pea, a primarily East African crop, to white yam farmers in West Africa. Pigeon pea is a shrub that can be planted in alleys and between white yams. The idea is to use the pigeon pea’s ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, thus amending the soil for the more valuable white yam crop. If the soil is improved, farmers can avoid clearing more land for farming purposes.

On top of its benefits to the soil, pigeon pea may function as a natural stake, eliminating the expensive practice of employing artificial stakes. Owusu Danquah emphasized that pigeon pea is a practical crop because it’s drought tolerant and has edible grains.

“The yam-producing area is mainly from the northern part and the middle belt of the country,” Owusu Danquah said. “Farmers in those areas don’t have much pigeon pea knowledge, and we want to increase that in an effort to increase the likelihood of them using our technology.”

By summer 2018, the research team should know whether the farmers’ needs are being met and if they are likely to adopt recommendations. Without the support of MSU, Owusu Danquah believes this research would not be possible. He is appreciative of the networking opportunities, and he can already see the positive effects of his work.

“I’ve had such a great environment to do research at MSU — building a network of colleagues,” Owusu Danquah said. “I would recommend any student come to MSU, definitely African students. My advisers tell me that even when you finish your degree program, you never really leave MSU. You take those connections with you back to your country, and that helps throughout your career.”

This article was published in Futures, a magazine produced twice per year by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. To view past issues of Futures, visit www.futuresmagazine.msu.edu. For more information, email Holly Whetstone, editor, at whetst11@msu.edu or call 517-355-0123.

Print

Print Email

Email