Cold damage to peaches

How to predict and assess winter damage to peaches and adjust growing practices according.

Predicting and accessing cold temperature impact on peach yields and tree health is tricky. However, experience over the years is a useful guide. Damage to fruit buds can be assessed by using a razor blade to cut fruit buds in cross section. For simple fruit buds such as peach and nectarine, a discolored center indicates the bud is dead. Using a hand lens is recommended for better viewing. For fruit types such as apple, pear, plum and cherry, the bud is complex containing multiple flowers and leaves. For these, it is easiest to determine viability in early spring if the branches are placed in water for a week or so to allow the buds to swell before cutting to look for individual flowers with discolored centers (Photo 1). Fruit trees typically have an excess of flowers, especially peaches and apples which require fruit thinning in most years.

Fall cold events

Impact of cold on tree health in the Michigan climate is often due to warm temperatures in late fall followed by a rapid temperature drop in December. Famous episodes in Michigan include the Oct. 10, 1906 drop to 10 degrees Fahrenheit and the Nov. 24, 1950 low temperature of -15 F, which resulted in massive peach tree losses.

Mild fall weather can slow the development of winter hardiness, especially when trees have significant nitrogen and water availability. This was the case in the winters of 2013 and 2014 when rapid temperature drops (50 to 60 F in late November down to the teens in early December) caused twig damage, which later appears as branch end dieback in the following spring (Photo 2). Branch end shrivelling of tree fruit was also noted in the late winter of 2019 in several areas of Michigan, presumably due to warm growing conditions late into the fall.

Decline of older peach and some apple orchards were seen in during spring greenup, in part due to low temperatures down to -22 F in southwest Michigan areas away from the protection of Lake Michigan. The impact was most severe on older trees with pre-existing health problems going into winter. Younger replant trees of the same varieties in the same orchard came through the cold spell with less problems.

Mid-winter cold events

Damage to the Michigan peach crop is most often due to mid-winter low temperatures, often associated with clear still nights or nights with wind coming from a direction that misses the warming influence of the Great Lakes. In general, when temperatures reach -13 F, damage to the relatively tender peach bud is expected. There is some evidence that a rapid drop in temperature is tougher on fruit buds than a slow decline, because a slow decline allow time the buds to acclimate.

|

Table 1. Mid-winter low temperature events in central Berrien County. Temperatures from 1994 and later are from MSU Enviroweather stations. |

|

|---|---|

|

Date |

Low temperature (F) |

|

Jan. 25, 1961 |

-17 |

|

Jan. 15, 1972 |

-17 to -20 |

|

Jan. 16 and 19, 1994 |

-17 to -22 |

|

Feb. 3, 1996 |

-13 to -17 |

|

Jan. 5, 1999 |

-13 to -17 |

|

Feb. 4 to 7, 2007 |

-4 to -14 |

|

Jan. 7 and 8, 2014 |

-9 to -23 |

|

Jan. 14, 2015 |

-9 to -23 |

|

Jan. 21 and 31, 2019 |

-9 to -22 |

|

Table 2. Typical critical temperature for mid-winter damage to fruit buds for varieties adapted to Michigan temperatures. |

|

|---|---|

|

Fruit Type |

Temperature (F) |

|

Apple |

-30 |

|

Apricot, pear, concord grape |

-25 |

|

Blueberry |

-25 |

|

Tart cherry |

-20 |

|

Raspberry |

-17 |

|

Blackberry |

-15 |

|

Plum, sweet cherry |

-15 |

|

Peach and nectarine |

-13 |

|

European grape |

-8 to -15 |

Assessing damage to twigs and branches

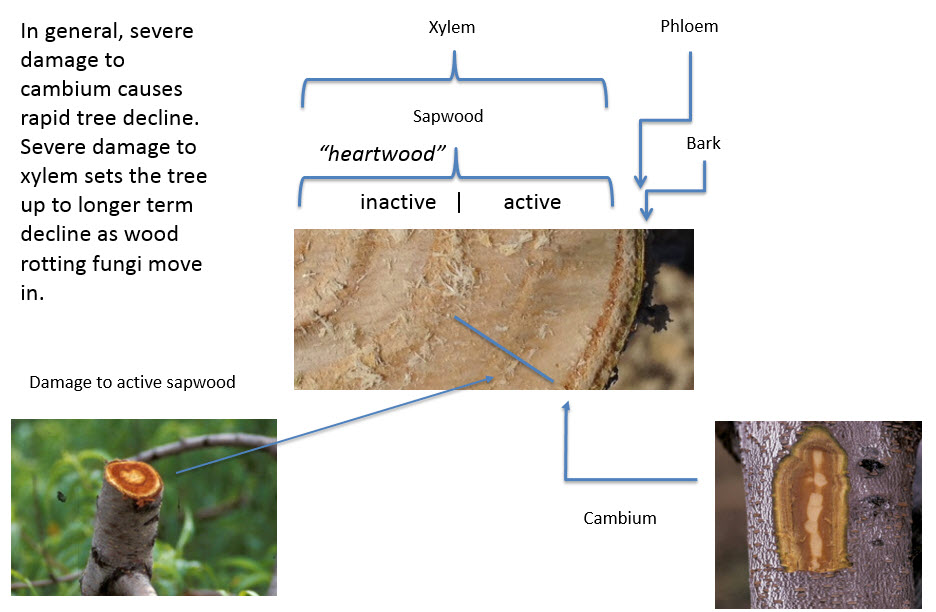

In general, we expect cold damage to peach and nectarine branches from rapid temperature drops in fall, as explained earlier, and with mid-winter temperatures below approximately -15 F. To assess damage, cut branches in cross section and slice below the bark layer to look at the cambium and young xylem areas (Photo 3). Cream-colored tissue is considered healthy, with damaged areas ranging from slight discolored to the dark cinnamon brown of severely injured tissue (Photo 4). Significant mid-winter damage to peach trees can shorten their productive life, but the impact depends in large measure on how healthy the trees were going into the freeze event (Photo 5).

The bark, cambium, phloem and outer layer xylem rings provide a protective shield around the inner core of xylem. As a tree ages, the innermost later of xylem (the heartwood) no longer is living, has no active defense against invaders, and has a primary role of supporting the tree (Photo 6). Trees with dark brown cambium lose the ability to grow and reduces ability of the outer layers to protect the heartwood from fungal and insect attack. Trees with severely damaged cambium are prone to bark splitting when growth resumes in spring. Small nails can be used close splits if detected within a few days of opening (Photo 7). Using wound dressing to treat split areas doesn’t seem to help.

Practices to help cold-damaged trees

Prune peach and nectarine at bud swell to pink (normal time). Prune with normal intensity; strong pruning is not advised while trees are recovering from cold damage. Try to minimize big cuts on the lower part of the scaffolds.

Trees, even supposedly tough mature apple trees, are less winter hardy if pruned from September to early January. Heavy summer pruning also reduces the carbohydrate reserves of a tree going into the winter. If a limb is dead, it can be removed anytime.

You may be tempted to prune hard to reduce tree height in years of no crop, but this may be a mistake if tree health is poor. Hedging tree tops to reduce height is too drastic—it is better to cut an upright limb to a strong side limb to maintain control of top growth.

Consider nitrogen program carefully—trees with little or no crop will require less nitrogen. Monitor growth of tree; if the average annual growth is less than 1.5 feet, the tree is prone to canker and winter damage. If growth is greater than approximately 2.5 feet, the tree is prone to fall cold damage. Be prepared to provide irrigation on sandy sites if soils become dry.

From the long-range perspective, you should have an ongoing schedule of orchard removal and replacement to have a range of tree ages. Winters differ in their impact on different age trees—having a range of tree ages helps insure a greater number of trees are in good shape for production next year. Adopt tree training practices in the early years of tree growth that minimize the need for big cuts in later years on the lower part of the scaffolds. Avoid heavy reliance on peach varieties with unknown winter hardiness, especially those from warm climate breeding programs such as those in California.

Print

Print Email

Email