Disease activity picking up in grapes

Disease symptoms are becoming more apparent. Continued monitoring and preventive fungicide sprays are advised to protect developing fruit after fruit set.

Symptoms of grape diseases such as Phomopsis cane, leaf spot, black rot and anthracnose have been noticed in Michigan vineyards on susceptible cultivars. Frequent rainy spells in early spring 2016 have helped the grape pathogens to come out of their dormant state and become active leading to infections on young shoots. Downy mildew has only been seen in wild grapes so far, and powdery mildew has not been observed yet. For specific fungicide recommendations, consult the Michigan Fruit Management Guide (E0154).

Phomopsis cane and leaf spot (causal fungus - Phomopsis viticola)

Disease symptoms were first noticed in mid-May as elongated, dark brown to black specks or streaks on the first one to three internodes of young shoots. These lesions will not produce spores this year, but will contribute to next year’s inoculum. Foliar lesions are also plentiful, primarily on lower leaves of the shoots and appear as small brown spots with or without a yellow halo. The infected leaves may be puckered. Many spots on the leaves and canes indicate high inoculum levels for rachis and berry infection. Rachis infections on flower clusters are visible already. Cool wet conditions favor infection: at least six hours of wetness are needed for infection at the optimum temperature (59-68 degrees Fahrenheit). A combination of cultural and sanitation practices as well as fungicide applications help in keeping the disease in check.

Phomopsis lesions on grape shoot. Photo: Tarlochan Thind, MSU Extension.

Black rot (causal fungus - Guignardia bidwellii)

Black rot symptoms have started appearing on unsprayed Concord and Niagara vines in Benton Harbor and East Lansing, Michigan, and first infections were noticed during the last week of May. According to the black rot model in Enviro-Weather, several infection periods have occurred during rainy periods. Consult the model for infection risk for fruit protection. The disease symptoms appear as small, light brown, roughly circular spots, particularly near old mummified berries. These can be distinguished from herbicide damage by the presence of a dark border around spots and small black pimple-like fruiting bodies, called pycnidia, in the lesions. Leaf lesions are an indication of disease pressure and may also contribute to fruit infection by rainsplash of spores from the lesions to the fruit. Fruit infection generally occurs around bloom and fruit set but symptoms only become apparent weeks later. The optimum temperature for disease development is 80 F, at which the wetness period required for infection is only six hours. At higher or lower temperatures, the wetness requirement increases. Protective fungicide sprays are very effective in managing this disease. Protect developing fruit for at least four to five weeks after bloom.

Young black rot lesions on Concord grape leaf. Photo: Tarlochan Thind, MSU Extension.

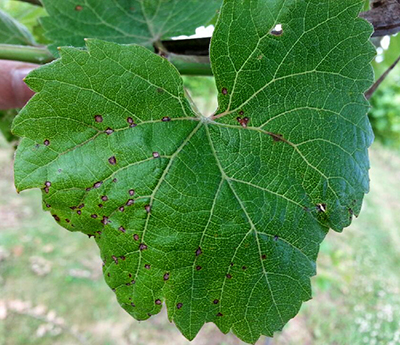

Anthracnose (causal fungus – Elsinoe ampelina)

Incidence of grape anthracnose has been observed on young leaves and shoots of some vines, including Marquis table grapes and Marquette wine grapes. Although a relatively minor disease, it can reduce fruit quality and yield, as well as weaken the vine. On leaves, symptoms appear as numerous circular to angular lesions with brown or black margins. The centers of older lesions become brittle and fall out, leaving a “shot hole” appearance. Lesions along the veins may cause curling and distortion as the leaves expand. On young shoots, lesions are oval, sunken, and purplish-brown with gray centers and raised edges, and can blight entire shoot tips. Infections on flower clusters may lead to twisting of the rachis, making the clusters resemble cork screws.

The causal fungus overwinters on infected shoots and spores are spread by wind and rainsplash. Anthracnose is especially severe in years with heavy rainfall early in the season. First disease symptoms are generally noticed two to eight weeks from budburst. Pruning out diseased wood and a well-timed spray program helps in managing anthracnose. A dormant application of lime sulfur should be made in early spring, prior to bud break. This can be followed by foliar applications of recommended fungicides from budbreak through early fruit development, when the berries are most susceptible to infection.

Anthracnose lesions on a Marquette leaf. Lesions are grayish or have holes in the center and often found along leaf veins. Photo: Annemiek Schilder, MSU Extension.

Downy mildew (causal fungus – Plasmopara viticola)

Downy mildew so far has only been observed on wild grapes growing close to the ground in humid locations. Systemically infected young shoots bearing heavy whitish sporulation on the lower leaf surface and stems appeared two to three weeks ago. Foliar lesions were first observed on wild grapes on June 5, 2016, and are increasing. Downy mildew has not yet been observed in cultivated grapes but is likely to appear any day now. Initial leaf symptoms appear as yellow spots on the upper leaf surface. These are termed “oil spots” because of their greasy appearance. On the underside of the leaf are corresponding areas of whitish, fluffy sporulation. Spores (sporangia) are produced during humid nights and are spread by wind. Rain or dew are needed for infection of leaves. The lesions eventually turn brown as the infected tissue dies. The disease can spread rapidly under warm conditions with frequent rain or dew and may lead to premature defoliation. Downy mildew is well controlled by preventatively applying effective fungicides. Alternating fungicides with different modes of action is extremely important for managing downy mildew, since it is a high-risk pathogen for the development of fungicide resistance.

Downy mildew lesion on wild grape leaf. Photo: Annemiek Schilder, MSU Extension.

Dr. Schilder’s work is funded in part by MSU’s AgBioResearch

Print

Print Email

Email