Harsh winter for wine grape buds

Sub-zero temperatures in February and March of 2014 may have affected vineyards in Michigan’s Grand Traverse region.

The wine grape vineyards of Michigan’s Grand Traverse region may have been impacted by a number of nights with sub-zero temperatures in February and March. The Michigan State University Enviro-weather system reported temperatures as low as -11 degrees Fahrenheit twice at the Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center (NWMHRC) in Leelanau County during the early morning hours of Feb. 28 and March 3, 2014. The East Leland Enviro-weather station recorded eight lows of -10 or lower in February and March, with a severely cold -24 on the morning or March 3. On Old Mission Peninsula, temperatures below -10 were recorded on seven dates: Feb. 11, 27 and 28, and March 2-5. The coldest reading was taken on the morning of March 3 at -20 F.

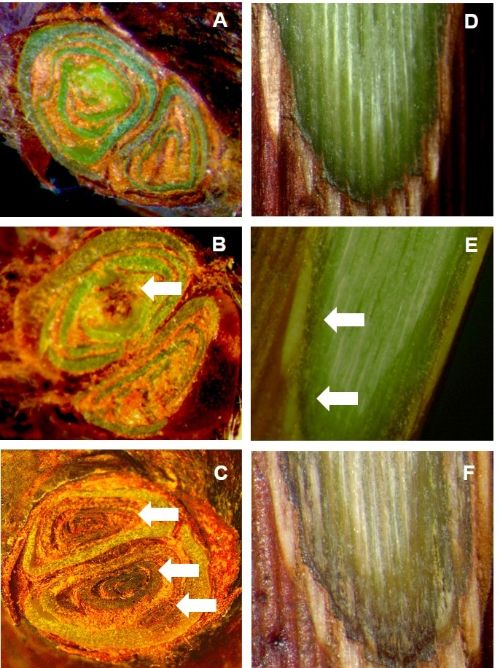

The photos at the right show cold injury to grape buds and canes: A) Healthy compound bud; B) Discolored tissues indicating injury to primary bud; C) Compound bud with cold injury to primary, secondary and tertiary buds; D) Healthy cane tissues; E) Moderate cold injury to cane indicated by discolored cambium tissues; F) More advanced symptoms of cold injury to cane.

Riesling and Chardonnay grapes, the mainstay white wine grapes of the Grand Traverse region (82 and 78 percent of the acreage of those varieties in Michigan are planted in Traverse City, Mich.), can typically tolerate temperature to about -10 F before significant injury occurs to buds. The primary red wine grapes in the region, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc (83 and 59 percent of the acreage of those two varieties are in Traverse City, Mich.) can also be expected to come through without a great deal of harm if the minimum temperatures are not below -10 F. However, under certain circumstances, the actual cold-hardiness of a grapevine may not be as low as expected.

If the harvest period in the preceding fall is very late, as it was in 2013, vines may suffer from a short “recovery period” between harvest and dormancy, a delayed acclimation phase with low stored reserves and a potential reduction of their cold-hardiness. Fluctuating winter temperatures, swinging back and forth from relatively warm to relatively cold, can also cause problems. It only takes a relatively short warming spell to reduce the cold-hardiness of buds.

Thirty-two varieties of wine grapes in the NWMHRC experimental vineyard were sampled on March 18 by collecting a minimum of 10 1-year-old canes per variety. Each node or compound bud of the sampled canes was carefully sectioned with a razor blade and examined under magnification to look for injured tissues. Grape have a unique, three-part compound bud with a primary bud that can bear the greatest amount of fruit, a secondary bud that has a bit more cold-hardiness than the primary bud but bears less fruit, and a tertiary bud that bears no fruit but is typically the most cold-hardy of the buds. Some bud mortality is seen every winter from a variety of reasons.

The loss of a large portion of the primary buds can be tolerated if a sufficient portion of the secondary buds remain alive, or if pruning practices can be adjusted to leave a greater number of total buds on the vine to grow and bear fruit in the coming season. See the Michigan State University Extension Bulletin E-2930, “Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection,” for further details on the structure of grape buds and techniques for assessing injury.

The results revealed good news and bad news, depending on the variety. Riesling showed a solid 84 percent primary bud survival rate with Chardonnay not far behind at 74 percent. Each had over 90 percent of their secondary buds alive and well. Pinot Gris and Gewurztraminer did not do as well, with just over 50 percent survival of primary buds; Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc both came in at under 50 percent live primary buds, but each of these varieties showed decent survival rates for the secondary buds, so it should be possible to adjust pruning practices to achieve a typical crop load for the 2014 season.

A number of other varieties exhibited much greater bud mortality. Pinot Blanc, a white grape growing in popularity in the region, had only 37 percent and 45 percent survival of primary and secondary buds, respectively. Gruner Veltliner, another white grape coming into use in Michigan, had under 5 percent of the primary and secondary buds alive in this sample. Eight other promising Vitis vinifera wine varieties being tested at the NWMHRC came in at under 30 percent primary bud survival. Some muscat varieties were also hard-hit by the cold. As would be expected, hybrid varieties faired much better, as cold-hardiness is one of the characteristics typically selected for in breeding programs. Several hybrid varieties showed greater than 80 percent survival of primary buds.

Based on this study of wine grape bud survival, it is highly recommended that growers carefully assess bud condition before proceeding with pruning; significant adjustments to vine bud counts may have be made to keep crop loads at desired levels.

A complete listing of the varieties that were examined and the bud survival percentages will be made available through the next NWMHRC FruitNet report, or by request if you send an email to me, Erwin Elsner, MSU small fruit Extension educator, at elsner@msu.edu. The MSU Enviro-weather website can be used to check the low temperatures at dozens of locations in Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email