How to manage unharvested or diverted cherries

Growers not harvesting a block of cherries should remove fruit from the trees and physically destroy it in an effort to reduce spotted wing Drosophila populations.

As growers are currently assessing their crops after the recent hailstorm, there are many considerations for how to handle cherries left in the orchard. This year, some growers will not be able to commercially harvest the crop due to the level of damage to the fruit caused by the recent storm. Additionally, because this year’s crop is large, some growers will be diverting fruit to obtain diversion credits. In either case, fruit that are left hanging on the tree due to damage or diversion will be a potential breeding ground for spotted wing drosophila (SWD).

Last season, there were cherries infested with SWD larvae, and as a result, growers have been diligent with SWD management programs this season. However, now that we are in the home stretch and in the midst of cherry harvest, growers are wondering what to do with fruit that will not be harvested. The Northwest Michigan Horticulture Research Center has a trial currently underway to help guide growers on handling a cherry crop that will be left in the orchard.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that fruit shaken to the ground and physically destroyed would decay and dry out faster than leaving fruit intact, either on or off the tree. Dried up/destroyed cherries would be a less suitable host for SWD reproduction and regeneration.

Methods

Ripe, unsprayed, Montmorency tart cherries were collected July 7, 2016. Fruit were collected without stems and the cherries were placed in a windrow in the center of the sod row middles. Piles of about 2 quarts of fruit were placed in a straight line along the sod row middle in an attempt to mimic the piles of cherries that come off the conveyer of a harvester and drop onto the orchard floor rather than into a cherry tank.

We put fruit down into two lines in the orchard; we smashed one line of fruit and left the other line of fruit intact. To simulate mechanically crushing or mashing of fruit by a farm implement, we positioned fruit in front of golf cart tires in the orchard row and drove over the piles of fruit (Photo 1). Because the tires of the golf cart were smaller than tractor or truck tires, we ran over the fruit twice with front and back tires. We collected samples of smashed and intact cherries one day, three days, five days, seven days and nine days after they were either smashed or placed intact on the ground (Photos 2-7). Each treatment was replicated five times.

Photos 2 and 3. Fruit crushed by golf cart (left) and intact fruit (right) on day of harvest.

Photos 4 and 5. Crushed (left) and intact (right) fruit on day five.

Photos 6 and 7. Crushed (left) and intact (right) fruit on day 12.

Following each collection timing (one day, three days, five days and seven days), the smashed and intact fruit were brought back to the laboratory and exposed to SWD adult flies. We placed a 4-by-4-inch square of fruit into bioassay containers (Photo 8). Fruit were placed directly onto a plastic mesh “net” inside a sandwich-size plastic container; the mesh and fruit were placed on top of a small sponge to soak up extra moisture. The 4-by-4-inch square of fruit that was placed on top of the mesh was approximately 1 inch in depth. Five male and five female SWD were added to each container. The number of SWD larvae per sample was counted after eight days for each of the collection timings (Photo 9).

Photo 8. Fruit placed into shallow bioassay containers for exposure to SWD adults.

Photo 9. First inspection for larvae on fruit collected on day one.

Conclusions

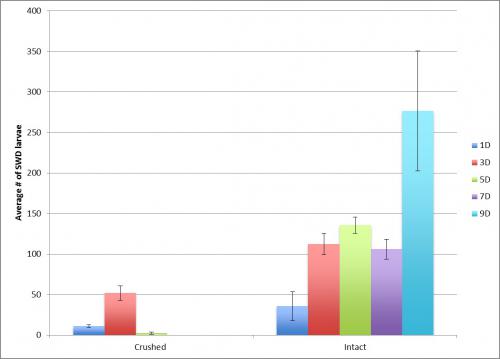

Results indicated that crushing the fruit in the orchard reduced the number of SWD larvae at all timings, one day, three days, five days, seven days and nine days after the initial crushing of fruit. Data showed that physically destroying fruit will be effective in reducing the SWD population in orchards where fruit will be left in orchards due to hail damage or diversion. However, growers should note that our experiment was completed during a relatively warm spell. During the duration of this trial when the fruit would have been in the orchard (July 7-13), the average temperature was 73.8 degrees Fahrenheit. There were three rain events, and the Northwest Michigan Horticulture Research Center received 0.27 inch on July 8 and 0.01 inch on July 11 and 12. We also had heavy dews on most mornings during this trial period.

At this time, Michigan State University Extension recommends growers who will not harvest a crop should put fruit on ground and smash or destroy the cherries as best as possible. An option for removing the fruit would be to use a traditional shaker (both halves of a double incline or a one-man shaker), and windrow the cherries to the center of the sod row middle. We crushed our fruit with a traditional tire (small tread), but flail mowers or cultipackers may work even better for destroying intact fruit. Tractor tire treads may be too deep for adequately crushing fruit, and smaller “piles” of fruit are more easily crushed than deep piles of cherries.

Average number of SWD larvae observed in five replications of crushed and intact fruit collected at one day, three days, five days, seven days and nine days after crushing or placing intact fruit on the ground.

Dr. Rothwell’s work is funded in part by MSU’s AgBioResearch.

Print

Print Email

Email