Lake Michigan baitfish at all-time low; young alewife dominate

Two methods are used by USGS biologists to monitor forage fish in Lake Michigan. The latest bottom trawl data from 2012 found combined-species biomass at its lowest level since surveys began in 1973.

Scientists from around the lakes gather each year to share their latest findings at the Great Lakes Fishery Commission’s (GLFC) Lake Committee Meetings. This year’s Upper Lakes Meeting took place in Duluth, Minnesota, on March 19-21. The majority of the presentations were recorded and are available to the public. The GLFC website provides links to videos on an impressive array of topics including native species rehabilitation efforts, invasive species control, contaminants, and food web changes.

One of the most troubling changes in recent years has been the decline of forage fish in Lake Michigan, which led to a decision to reduce the number of predators stocked in the lake. Biologists from the U.S. Geological Survey, in collaboration with Michigan Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, survey the forage base each year. The results from 2012 surveys were shared in a presentation at the Upper Lakes Meeting, and reports including the most recent data can be found at the USGS Great Lakes Science Center website.

Perhaps the worst of the bad news is that 2012 bottom trawls found the lowest total weight (biomass) of combined prey species recorded in Lake Michigan since trawl surveys began in 1973. Bloater, rainbow smelt, deepwater sculpin, and ninespine stickleback were all at historic lows. Round goby and alewife (both non-native species) accounted for over 75 percent of prey fish biomass.

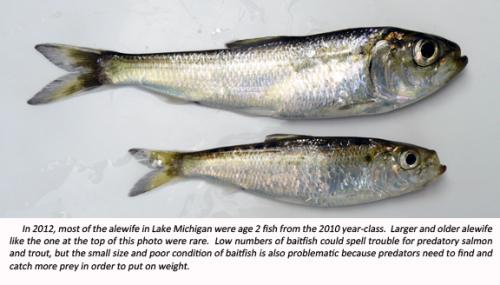

Alewife are an important food source for salmon and other predators, but alewife are known for their boom-and-bust nature. Some years produce an abundant alewife  year-class and other years produce nothing. In the past, alewife commonly lived for six to seven years, and even nine year olds were not unheard of. This provided some insurance in the event of a weak year-class or two.

year-class and other years produce nothing. In the past, alewife commonly lived for six to seven years, and even nine year olds were not unheard of. This provided some insurance in the event of a weak year-class or two.

Bottom trawls in 2012 found that 84 percent of large (>100 mm) alewife were age 2, and the oldest fish captured was a four year old. Acoustic surveys were also conducted in conjunction with midwater trawls. A single five-year-old alewife was captured during the acoustic survey, but the estimate of dominance by age 2 alewife was even higher (89 percent).

Acoustic surveys have not been in use for as long as bottom trawls, but they provide a useful and complementary tool for assessing the health of the forage base. One thing that acoustics are particularly good at is measuring the abundance of the smallest baitfish in the lake. Because of this, acoustic surveys provide a more reliable estimate of year-class strength. In 2011, acoustic surveys found an exceptionally weak hatch of alewife, but 2012 produced a crop that was only slightly weaker than average.

Using both sets of historical data, USGS scientists developed a rough prediction for (large) alewife biomass in 2013. Given the inherent unpredictability of nature in general, and alewife in particular, the range is fairly wide. The forage base could decline or increase over the coming year, but given the increase of young alewife from 2011 to 2012, the outlook is cautiously optimistic.

Print

Print Email

Email