Michigan vegetable crop report - July 21, 2022

The disease and insect management season is upon us.

Weather

Watch Jeff Andresen's weather update here.

It has been a drier than normal week for most of the state, and hot. Degree day totals are several days behind normal in the Upper Peninsula increasing to several days ahead in the south.

The forecast calls for:

- Variably cloudy, warm and windy Wednesday with scattered showers possible, especially north.

- Mostly sunny, warm and dry Thursday and Friday.

- Warm with increasing clouds Saturday. Showers and thundershowers possible Saturday night into Sunday, especially south.

- Fair and cooler early next week.

- Daytime temperatures in the 80s to near 90 through Saturday, cooling to the 70s to low 80s by early next week. Lows generally in the 60s through Saturday falling back to the 50s and 60s by Monday.

- Medium range guidance suggests some pattern changes across North America, with somewhat cooler temperatures and more frequent chances for precipitation during late July into early August.

Minimizing plant stress during hot times

The challenges vegetable growers are facing due to the lack of rain across the state are difficult to manage, especially on sandy soils and if irrigation is not an option. Common irrigation types may be overhead sprinklers or drip-lines that are often placed under plastic mulch (see “Plasticulture for Michigan Vegetable Production” by Michigan State University Extension). Irrigation can be a good investment for your business even under more normal conditions, where it can keep crops from losing quality and promote growth. But during extreme heat and drought irrigation may be what simply keeps plants alive. The old saying “water slow and deep” is a good rule of thumb. Deep irrigation encourages deeper root growth, providing greater opportunity for plants to not only take up water but also nutrients.

Timing of irrigation is also important. Overhead sprinkler irrigation that is timed to allow leaves to stay wet for most of the day and all night are risks for disease (see “When is the best time to irrigate the garden?” from Iowa State University Extension). Many plant diseases require water for mobilizing infections to new tissues and allowing foliage to dry before sunset can reduce disease opportunities. If drip irrigation is not an option, following a morning schedule for sprinkler irrigation is the best approach to reduce disease infection opportunities.

Mulches of all types help reduce soil water loss especially during periods of high temperatures (see “Mulch Improves Water Conservation in Vegetables” from Specialty Crop Industry). Mulches may be manufactured materials such as black plastic or organic products such as wheat straw that can be incorporated into the soil following the last harvest. Mulches can save what precious water there is and reduce plant heat stress

Black plastic beds are a double-edged sword that can cut the other way during extreme heat. Their ability to absorb the sunlight increases the soil temperatures and air temperatures around the plants. Excessive temperatures cause flower abortion, transplant death, and in some cases lower quality broccoli heads, and “cooked” sweet onions where they touch the plastic (see “Plastic Mulch Primer” from University of Vermont Extension). To reduce light absorption, one temporary action is to apply kaolin clay (Surround) as a reflective layer onto the surface of the plastic. A study in Virginia, “Kaolin clay may serve as sunblock for tomatoes,” showed that kaolin clay was effective but needed to be reapplied as it faded due to rains.

Vegetable fields without plastic mulch may consider spreading straw mulch between rows to reduce water loss to evaporation as well as lower soil temperatures as an emergency action now or include as a future practice. This approach would be especially beneficial if you laid the mulch after the next rain event to hold in the moisture in between the rows. Wheat harvest has begun so straw will be in ready supply. When choosing straw, select bales that are nearly weed-free and without wheat seed to minimize adding to the field’s weed-seed bank.

If you use wood chips in pathways, take into account that the Carbon:Nitrogen ratio of wood versus straw is double (100 wood chips versus 40 straw). Since all organic products start to break down once they have access to water and nitrogen, the chips will use nitrogen that is likely intended for the crop. The higher percent of carbon the more nitrogen needed to break down the organic product. So carefully monitor the nitrogen of your crops especially if you use wood chips as a mulch and reduce crop stress. These suggested actions can help your crops get through this time of stress. With any steps you take, be sure to take notes so you are better prepared for the next time.

Herbicides and high temperatures

With summer plantings for fall harvest taking place, and post-emergence weed control in various crops, it might be nice to re-review some patterns with herbicide application during hot weather (originally written in our June 15 report).

In general, systemic herbicides are less effective in hot conditions, and contact herbicides are more effective both on the weed and in injuring crops. Some chemistries are more prone to volatilizing and moving off target in hot weather.

Remember that the efficacy of postemergence applications is mainly dictated by weed size. Spraying weeds beyond the size range recommended on the label will result in poor weed control. Along with environmental conditions (temperature and rainfall) weed control efficacy will also depend on the type of herbicide application, the rate applied, and the physiological status of the target weed. The ideal temperature for applying most post-emergent herbicides is between 65 F and 85 F. If weeds are damaged or under stress before the herbicide application, then control will be reduced due to the decreased herbicide absorption into the plant.

Read more about the impact of hot and dry on herbicide efficacy from the University of Florida, and some other important concepts are covered in this Kansas State University article.

Disease, or something else?

Growers are often faced with confusing symptoms that are hard to diagnose. A diagnosis from a lab like the MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics lab is critical and should be sought. Providing observations to the diagnostician along with the samples is important and includes the pattern of symptoms. In some instances, the problem is not a disease that requires a fungicide but could be the result of a nutrient deficiency or something else unrelated to a pathogen.

Look at the pattern exhibited by individual plants and across the entire field, hoop house or greenhouse. Yellowing between the veins of a leaf can be common and is typically not a disease problem.

Looking across fields, flats or plant beds, disease symptoms are usually observed in smaller, localized areas, while environmental or nutrient stress problems are seen across wider areas.

Don’t forget to look at the weeds. If weeds are showing similar symptoms to the crop, it may mean a non-disease factor is at work.

Crop updates

Asparagus

Why are there skips in part of my field? Why are some fern stunted? Do I have Fusarium or Phytophthora? While Fusarium and Phytophthora affect the crown, the best clues to what’s going on during the growing season are above-ground. First, look for symptoms of these diseases in the fern. Phytophthora-infected crowns can produce shoots that come up, abort, and “crook.” You can see these at the base of plants. Fusarium infected plants can produce bright yellow ferns that stand out from the normal green The pattern also provides clues. Phytophthora asparagi may be worse in areas where water washes or does not drain as readily, though that’s not always the case. On the other hand, Fusarium can be worse in light spots and/or areas with a low soil pH. Both diseases will result in skips and “holes” in the field as plants eventually die.

Why can’t we test crowns? Fusarium is present in most fields and there are different species. While recent MSU studies show that most of the Fusarium isolated from crowns causes disease, not all Fusarium is pathogenic. On the asparagus Phytophthora front, MSU and other labs discovered it is next to impossible to isolate the pathogen from actively growing roots (though it can be isolated from infected spears during harvest and dormant crowns). This means testing crowns during the growing season is not helpful.

Ultimately, not a whole lot can be done once Fusarium or Phytophthora is established in asparagus fields. However, it is helpful to know which pathogen is an issue so that steps can be taken to avoid these same problems when establishing new fields. For instance, make sure that the soil pH is adjusted prior to planting (for Fusarium) and purchasing healthy crowns (for both pathogens) soaked with Cannonball (for Fusarium). Keeping plants healthy in the establishment years should also help for Fusarium, as it has more of an impact on stressed plants.

Other things can cause skips or holes in fields, too, such as repeated deer browsing along field edges and herbicides oops-es.

Carrots and celery

As of July 15, scouts report that growers are in aphid-management mode, with colonies detected now in a few counties. Aster leafhopper numbers are locally high on some farms but infectivity with aster yellows is low at most locations. Variegated cutworm moths are present in traps in some locations but less so in others. Celery leaftier moths are flying around, though numbers are not huge. Leafhopper numbers are high in some locations but infectivity with aster yellows is low. Slugs have also been causing issues in known problem spots. On the slug front, pelleted products containing the active metaldehyde or iron phosphate can be helpful, make sure to read the labels.

Cucurbits/Pickles

Melon harvest is picking up, and slicing cucumbers and summer squash harvest is strong. Pumpkin and hard squash are flowering and setting fruit on early planted varieties. Some growers are putting in a final set of pumpkins this week, limiting themselves to short-day varieties and transplants on plastic to make sure they ripen in time for the Halloween market.

Mechanical harvest of commercial pickles started this week. Downy mildew sporangia have not been detected in our statewide monitoring program in the last couple of weeks. Downy mildew on cucumbers was found in Ohio in an unsprayed field.

Several calls came in about powdery mildew, because “plants are big, and this is about the time we see it.” Fungicides can wait until there is active, rigorous field scouting reveals the beginning of the disease. Knowing when the pathogen first comes into a production field is important so that a management strategy can be put into place when the pathogen is actually present (not wasting money) and before the problem is out of control (not chasing from behind). Next week will feature an updated fungicide recommendation program. You can review last year’s for now.

Squash vine borer caterpillars are starting to make their presence obvious as they feed on the inside of the stem and collapse plants. Timing insecticides is difficult because eggs are laid at the base of plants and baby caterpillars immediately burrow into stems out of reach of contact insecticides. Frequent insecticide applications in squash tend to flare up aphids later in the season by reducing natural enemies, but when applied early enough in the moth’s egg-laying period this is not typically a problem. A colleague at Cornell, Abby Seaman, shared that a study they performed found that Entrust and Bt aizawi (Agree or XenTari) applied once per week for three weeks starting at 1,000 growing degree days base 50 (GDD50) was an effective organic measure and it also did not flare up aphids. She also noted that 1,000 GDD50 was about the time that chicory starts blooming on the roadsides.

Onions/Garlic

With last week’s cooler temperatures, onion thrips numbers have remained relatively moderate. As onion thrips adults are increasing in number, this is no longer a good time for Movento applications. With the upcoming heat this week, expect thrips numbers to increase quickly and consider applications of Radiant if a three thrips/leaf threshold is surpassed. For more information on insecticides, see Cornell’s guidelines for onion thrips management. This table includes recommendations for insecticides and onion thrips threshold to be used for different insecticides.

Peas/Beans

Rust has been reported. Fungicides from FRAC groups 3, 7 and 11 work well for this pathogen. Here is a short list of fungicides from the Midwest Vegetable Guide.

Fruiting vegetables

Field tomato and pepper are ripening fruit, with some light harvest beginning of small or immature fruit. Eggplant harvest has begun in some places and smaller varieties.

Several growers reached out this week sharing pictures of plants exhibiting wilt symptoms that are likely caused by Verticillium or Fusarium pathogens. These soil-pathogens are hard to tell apart, but are managed similarly: with at least a four-year rotation, and resistant varieties. There are lots of Fusarium and Verticillium-resistant variety options for tomatoes, but very few Verticillium-resistant eggplant varieties exist, and so rotation and fumigation is the primary management tool for commercial eggplants. Interestingly, eggplants can be grafted onto tomato rootstocks, and so a potential bypass is available there as well if you can afford it. One could save some money by choosing a cheaper tomato hybrid with Verticillium resistance instead of a more expensive dedicated rootstock variety.

Read more in this Kentucky State University article, “Fusarium & Verticillium Wilt of Tomato.”

A nice list of resistant tomato varieties and eggplant varieties has been compiled by Meg McGrath at Cornell.

For more information on the grafting solution, checkout this research paper, “Grafting Eggplant onto Tomato Rootstock to Suppress Verticillium dahliae Infection: The Effect of Root Exudates.”

Some wilts are not caused by diseases, but by caterpillars that bore into stems. The common stalk borer, Papaipema nebris, is a moth caterpillar that lays eggs in grass in the fall, and in May-July the caterpillars crawl to nearby large-stemmed plants like tomatoes, potatoes, beans, and ragweed. Like squash vine borer, it is a rather unpredictable and spotty pest in commercial settings.

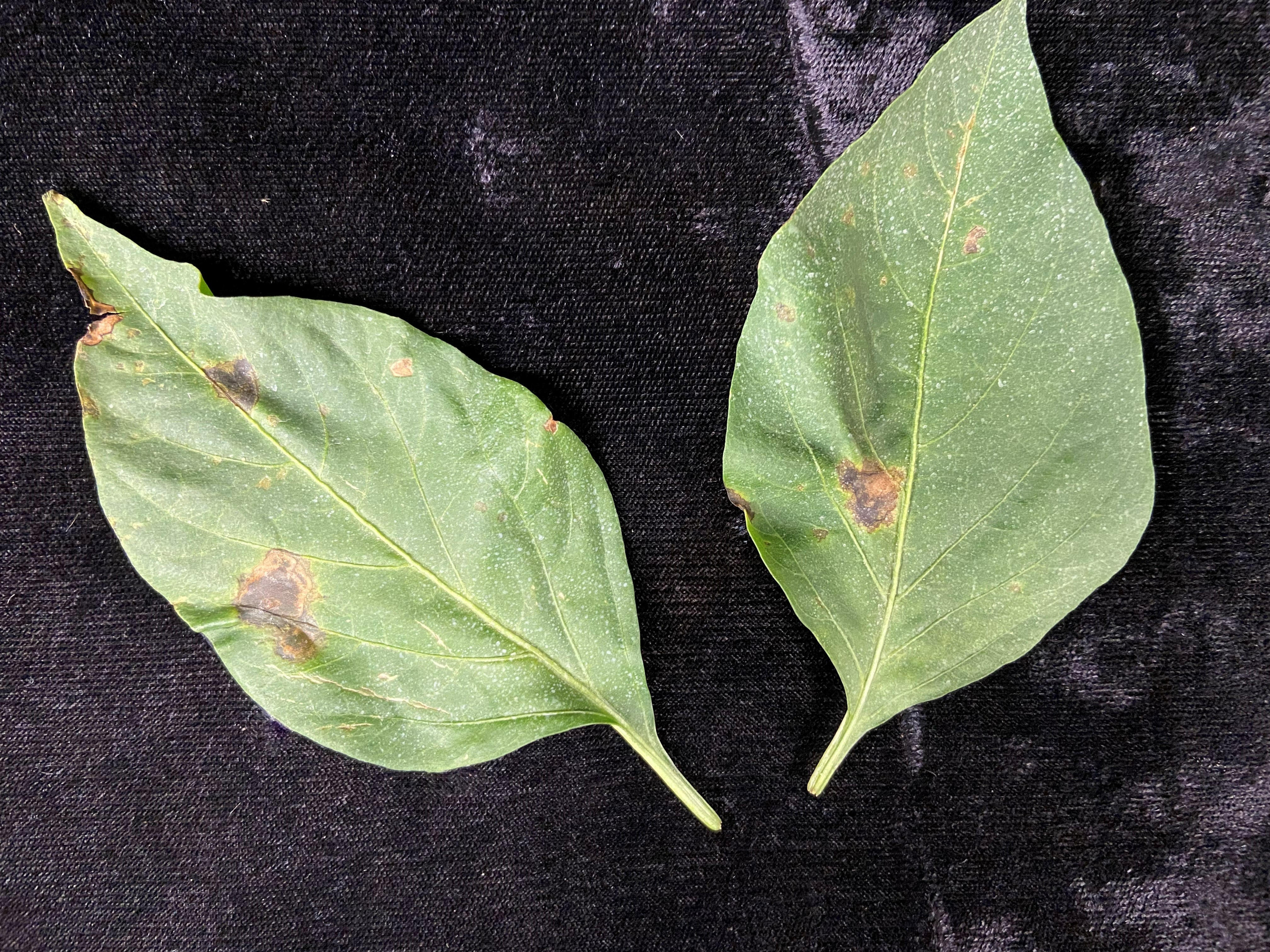

Bacterial leaf spot caused by Xathomonas is showing up on both tomato and pepper plantings. Symptoms on foliage are readily visible when walking fields, look for dark, irregular water-soaked lesions on the foliage. As symptoms progress, spotting also develops on fruit. Severe disease in pepper can result in leaf drop, leaving the exposed fruit vulnerable to sun scald.

Sweet Corn

Sweet corn harvest has begun across the region. Light earworm pressure on harvested ears has been reported, which matches what we are finding in traps (not much, but some). What to use for corn earworm? Trap captures can help guide you. Past work at Ohio State University suggested that pyrethroids can be effective when trap catches are low—check out the helpful article, “Pyrethroids’ effectiveness against corn earworm eyed.” There are a wide variety labeled, including old standbys like Warrior II, Brigade, Baythroid, Mustang Maxx, Hero and their generics. These can provide affordable control when pressure is not high. When trap captures are higher, products containing the active ingredients chlorantraniliprole or spinetoram are helpful. There are both one-active versions of these (e.g., Coragen and Vantacor for chlorantraniliprole, Radiant for spinetoram) as well as pre-mixes with pyrethroids (e.g., Besiege, Elevest) or other insecticides (e.g., Intrepid Edge). Check pricing, check traps, spray, and hope for the best!

It has been a drier than normal week for most of the state, and hot. Degree day totals are several days behind normal in the Upper Peninsula increasing to several days ahead in the south.

Events

- July 27: Viticulture Field Day at the Southwest Michigan Research and Extension Center. The center is located at 1791 Hillandale Road in Benton Harbor.

- Aug. 4: Potato Field Day from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the Montcalm Research Center. The center is located at 4629 W. McBride Road in Lakeview. Presentation topics include sustainability, irrigation and potato storage management.

- Aug. 10: Turf Field Day at the on-campus Hancock Turfgrass Research Center. The center is located at 4444 Farm Lane in Lansing.

- Aug. 11: Field Day and Pasture Walk at the Lake City Research Center. The center is located at 5401 W. Jennings Road in Lake City and works primarily in livestock management.

- Aug. 23: Plant Diagnostic Day at the Saginaw Valley Research and Extension Center. The center is located at 3775 S. Reese Road in Frankenmuth.

- Aug. 24: Blueberry field day at the Trevor Nichols Research Center. The center is located at 6237 124th Ave. in Fennville, Michigan.

- Aug. 25: 2022 Tile Drainage Field Day at 13000 Bird Lake Rd, Camden, MI.

- Sept. 8: Field Day at the Northwest Michigan Horticulture Research Center. The center is located at 6686 S. Center Highway in Traverse City and will highlight Michigan fruit advancements.

- Sept. 14: Mechanical Weed Control Field Day at the Southwest Michigan Research and Extension Center. The center is located at 1791 Hillandale Road in Benton Harbor.

Print

Print Email

Email