Monitoring for spotted wing Drosophila larvae in cherries before entering processing facility

Guidelines for inspectors to detect fruit infested with spotted wing Drosophila (SWD) larvae at the receiving station or prior to entering the processing facility.

Spotted wing Drosophila (SWD) is the primary pest of concern for the 2016 harvest season in cherry orchards. This pest has the reproductive capacity to build populations quickly in the field, and controlling large numbers of SWD is a challenge in commercial orchards. Most tart and sweet cherries are susceptible to SWD infestation at this time, and growers will need to maintain tight spray programs to control this pest to deliver SWD-free fruit to the processing facility. Furthermore, processors and receivers would prefer to detect SWD-infested fruit before it enters the processing facility. Below are some guidelines for setting up a procedure to inspect for SWD-infested fruit at a receiving station or prior to fruit entering the processor.

Michigan State University Extension recommends a salt solution be used for rapid fruit sampling for SWD. Inspectors should collect subsamples of fruit from the harvested tanks of cherries. Fruit that is infested by SWD will have some distinctive characteristics, which may not be readily identified without practice; however, once inspectors have seen SWD-infested fruit, they develop a good eye for detecting them.

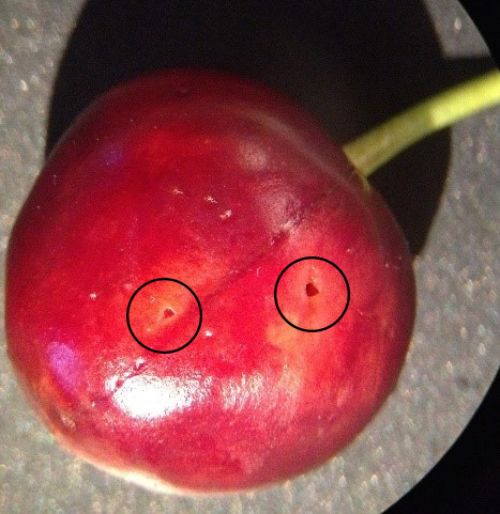

For instance, cherries with SWD larvae will have oviposition scars – tiny, circular puncture holes that grow as the cherry starts to break down (Photo 1). These puncture holes are distinct and unlike the crescent-shaped oviposition scars caused by plum curculio. Often, especially when the SWD infested fruit are intact, the fruit have a leaky appearance around the oviposition scars, and droplets of cherry juice emerge from the scars when the fruit is slightly squeezed (Photo 2).

Leaky fruit.

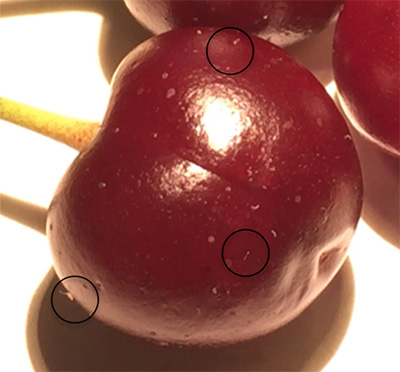

SWD eggs are laid into fruit; however, these eggs are quite distinctive and can be differentiated from other pest species eggs (cherry fruit fly) as SWD eggs have two breathing tubes. These tubes are often visible with the naked eye, and these tubes can be observed sticking slightly out of the fruit (Photo 3).

Spotted wing Drosophila eggs.

Additionally, fruit that has SWD larvae will also have a bruised appearance, and sometimes slightly sunken where the eggs were laid. Montmorency cherries have a darker color (less than bright red color) in the area when the females laid the egg in the fruit. Infested fruit often have a vinegary or overripe smell, which may not be detected unless the level of infestation is quite high or when the fruit has not been placed in water.

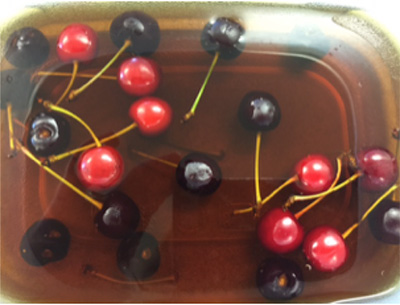

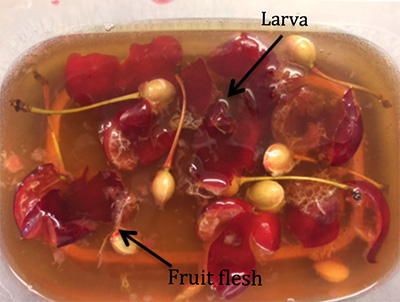

Once the inspector performs a quick visual inspection (as mentioned above), the subsample of fruit should be placed into a salt solution to test for live SWD larvae (Photo 4); larvae will wiggle out of the holes in the fruit or at the very least the larvae will stick their posterior ends out of the fruit, giving the cherry a “whisker-like” appearance (Photo 5).

Salt bath solution.

Larvae emerging from cherry.

Salt solution recipe and methodology

- Dissolve 1 tablespoon salt per 1 cup warm water. Warm water reduces the time it takes for the larvae to exit the fruit; cold water will reduce larval activity.

- Fruit should be slightly squeezed before placing it into the salt solution. SWD larvae do not like to be disturbed and will more readily exit the fruit when pressure is applied to them. Inspectors should not squeeze the fruit enough to break the skin of the cherry as the flesh of the Montmorency has whitish-colored veins that can be mistaken as SWD larvae (Photo 6). Inspectors should only squeeze the cherries enough to disturb the internal larvae.

- Place fruit in a shallow pan and cover with salt solution. Fruit will float at the surface, so the inspector should be sure to swirl the fruit every few minutes to make sure all fruit are exposed to the salt solution.

- Fruit should remain in the salt solution for at least 10–15 minutes to observe larvae exiting the fruit.

- Inspectors should have a good hand lens (at least 15-20x, 30x is better; the higher the magnification, the better) and good lighting to see small larvae. Even the most seasoned entomologist will have difficulty detecting first instars as they are better observed under a microscope. However, if no microscope is available, second instars and older larvae are visible with the naked eye. If a quantitative sample is necessary, inspectors should count the larvae quickly while they are still alive and moving.

Montmorency cherry and SWD larvae.

The larval stage of SWD can be difficult to identify. The SWD larvae look like a maggot (Photo 7), which unfortunately look like cherry fruit fly larvae. However, if there is a relatively large infestation/multiple larvae, we can assume that all or most larvae found in a sample are SWD as past infestations have shown SWD can lay multiple eggs and multiple larvae can pupate inside a single fruit. The Northwest Michigan Horticulture and Research Center would be happy to assist in identification, so please do not hesitate to call us at 231-946-1510.

SWD larva on cherry.

Dr. Rothwell’s work is funded in part by MSU’s AgBioResearch.

Print

Print Email

Email