What will the Lake Michigan salmon stocking cut mean for Michigan anglers?

Mass marking of Chinook salmon sheds new light on the relative importance of Chinook salmon stocked in Michigan.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the modern Great Lakes salmon stocking program. When coho and Chinook salmon were first planted in the Great Lakes the results were spectacular. A nuisance invader (the alewife) became the prey of choice for salmon and fueled the birth of a world-class sport fishery.

Fifty years later we are struggling to adapt to the influence of new invaders, particularly quagga mussels and round gobies. Fishery managers also must adapt to the rising importance of natural reproduction, which now accounts for the majority of Chinook salmon in Lake Michigan. On top of that, the experience of Lake Huron’s alewife/salmon collapse in 2004 serves as a constant reminder that stocking too many Chinook salmon on top of wild fish can lead to disaster for coastal communities.

With this in mind, state and tribal agencies of the Lake Michigan Committee decided to reduce the number of salmon and trout stocked in Lake Michigan. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources recently announced its plan to reduce Chinook salmon stocking by 230,000 (in addition to reducing lake trout by 270,000 and cutting coho salmon stocking by 96,000).

Public reaction to Chinook salmon cuts in Michigan has been mixed, with a narrow margin of support from groups like the Lake Michigan Citizen’s Fishery Advisory Committee and Michigan Steelheaders (MSSFA) and opposition from Michigan Charter Boat Association and the newly-formed Great Lakes Salmon Initiative. What will the decision really mean for anglers?

Michigan stocking sites contribute little to Chinook catches

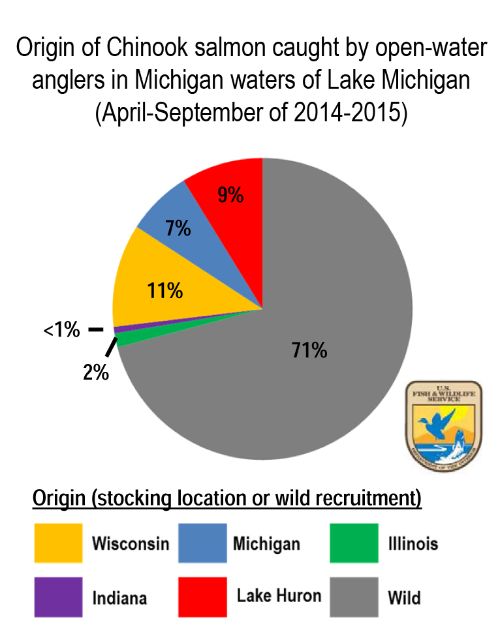

According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Great Lakes Fish Tag and Recovery Laboratory, only 7% of Chinook salmon caught in Michigan waters during the open-water fishery (April – September, 2014 – 2015) were stocked in Michigan waters of Lake Michigan (see figure). Roughly 7 out of 10 Chinook salmon caught in Michigan waters of Lake Michigan were wild, and Wisconsin and Lake Huron plants contributed more than local stocking efforts.

For Michigan anglers, this means that Michigan DNR’s 46% reduction in Chinook salmon stocking absolutely will not cause a 46% reduction in open water Chinook catches. After all, the vast majority of fish being caught by Michigan anglers are not Michigan-stocked fish (see factsheet for full details and results for other states).

Fewer stocked salmon does not necessarily mean fewer salmon in the lake

According to the Michigan and Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, about 6.8 million untagged/un-fin-clipped Chinook salmon smolts recruited to the population in Lake Michigan in 2012. While they believe that most of these unmarked fish were from wild, natural reproduction in Lake Michigan tributaries some did come from natural reproduction in Lake Huron tributaries and other sources. A small number of unmarked Chinook salmon smolts came from Salmon in the Classroom stockings (<10,000 unmarked fish) and from private hatchery stockings in Ontario waters of Lake Huron (214,352 unmarked fish). Even if all of these unmarked stocked fish migrated into Lake Michigan, the estimate of wild smolts recruiting to Lake Michigan in 2012 would be in the neighborhood of 6.6 million.

In 2013, wild reproduction fell dramatically to around 1.4 million smolts. Reasons are not entirely clear but, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, may have been related to low water levels and warm water temperatures during the fall spawning migration that produced those smolts. Other possible reasons include low survival due to an abnormally cold and prolonged winter, slow growth and high mortality of young salmon after hatching, and/or low numbers of alewife to feed on once young Chinook salmon entered Lake Michigan.

One way or another, natural reproduction was dismal in 2013 and remained below average in 2014 (2.9 million smolts). The poor fishing many Michigan anglers experienced in 2015 and 2016 was due, in part, to these weak wild year-classes.

The overwhelming influence of natural reproduction

Back in the early days, fishery managers could control the number of Chinook salmon in Lake Michigan through stocking. If states stocked 2 million Chinooks, then that was it — nothing more to account for, no more mouths to feed.

Now fishery managers have much less control over Chinook salmon numbers. Lake Michigan stocking (from all states) is being reduced from 1.80 million in 2016 to 1.35 million Chinook salmon smolts in 2017. Wild spawning salmon produce around 4.5 million smolts on average, but this wild production can range from 1.4 million smolts to over 6.6 million smolts. This is a lot of variation!

To put stocking into perspective, the total number of Chinook smolts (stocked + wild) produced in 2017 is expected to be around 5.85 million based on an average year of natural reproduction. However, if natural reproduction is poor this could be as low as 2.75 million. If natural reproduction is high, which is a distinct possibility, we could have upwards of 7.95 million smolts entering Lake Michigan in 2017. In short, the impact of the stocking cut amounts to very little in comparison to this tremendous variation in wild fish.

For anglers, the bottom line is that there is good reason to expect the number of Chinook salmon in Lake Michigan to increase or remain steady despite the recent stocking reduction. If salmon numbers do dramatically increase, as they might due to natural reproduction, the result could be a permanent collapse of alewife and salmon.

If natural reproduction remains near recent lows, the worst-case scenario for anglers would be a slight reduction in the number of salmon over the short term. In reality, this worst-case scenario would also be the best-case scenario in terms of ensuring the long term viability of the salmon fishery because it would provide a better chance of alewife recovery.

For better or worse, the future will be determined in large part by wild fish.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 33 university-based programs.

Print

Print Email

Email