Weather Outlook for 2021 in Michigan, Our Changing Growing Season Trends

February 19, 2021

Video Transcript

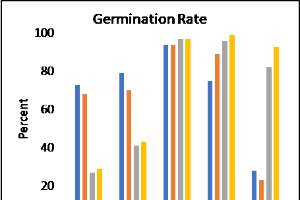

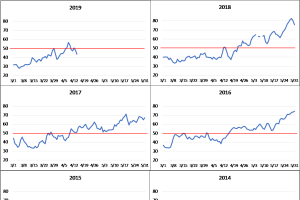

Timely given where we've been here over the last couple of weeks. But a, an interesting formation of ice here, relatively smooth ice, of course, most years the combination of wind and wave action on this part of Lake Superior result in piles of ice. And but but this year, the freezing of the harbor came relatively quickly and allowed a smooth surface. So people have been able to go out and take advantage of all this ice. And if actually, if you're, you're interested in just need a little bit of downtime here to, to look at something interesting. There's a lot of video has been taken of people skating here downtown area down in that one, the harbor front and in market again, taking advantage of this, this onset of winter, we've header of the last couple of weeks. And if you can't make it to the very, very end of the presentation here, I guess I'll, I'll cheat and just say there are big changes coming here is early as the beginning of next week. So again, the, the Arctic outbreak that we've dealt with were at the very end stages of it now and again, I'll get there at the end. But in general here, I'm going to look here at a little bit of a review of the growing season last year. Gonna talk then about some, some climatological trends over where we are right now currently in the last couple of decades. And then end with an outlook of where we're headed for the near term future. But I'm going to start, as I mentioned with review of last year and the growing season. And I'm going to start with a daily temperature summary from April through the middle of November. And if you're not familiar with this, this type of a graphic here, we've got our blue values. Here are the max and minimum temperatures. I'm using Lansing sort of in the middle of the state as a representative site. And again, this is an individual location. But the things to note here I think, are basically in the background, this area in brown. These are where the normal max and minimum temperatures are for that particular day and the time of the year. And then the on the top here in the sort of the, the light red, those are the record values for that given day. And then on the blue on the bottom, those are the record minimum. So it gives you an idea again, most of time, ideally we should be or we'd, we'd like to see temperatures close to being in this brown area. And you can see that early last year during the spring that we did have a couple of cold outbreaks. One during the month of April and then another here, the second week of May. But other than that, then it got mile and got more moderate. And we had during most of the growing season here, especially the summer, june, July, and August with a couple of exceptions, but most of it was at or above normal temperatures. You can see a lot of high temperatures, especially above the normal range, the date. And then into the fall we got a lot more variability. Couple of outbreaks of some cooler Canadian origin air all the way into the end. And I note here this, this, this very unusual week or 10 day period in November where we were actually at or near record high temperatures. I'm going to get back to that. That one's an interesting one, especially with regard to the fall harvest season last year. And I'll talk more about that here in a second. But in general, again, the growing season, if you look at all of the Statistics of it a little bit warmer than normal in most parts of the state. And it really dependent greatly on where you weren't terms of precept. I'll mentioned that in just a second. There was though, a couple of the highlights of the season or low lights, if you look at a number of ways. But we did have a significant freeze outbreak that occurred during the second week of the month. And you get to hear eighth through the tenth. Although in northern parts of the state we had freezing temperatures as many as ten days in a row, which again for for northern parts of the state, even that is unusual, but occurred across much of the Upper Midwest and the corn belt. And you can see the graphic here from the USDA's a world outlook board. Put this together. But lots of temperatures here in Michigan, even in primary growing areas where we saw the middle and upper 20s for, for minimum temperatures. We did have at that point in time, some crop came up, even some soy beans that have come up that were nipped or frozen back, frost it back a little bit. But I think overall, as we look back at this, it could have been much worse than it was because of the cool conditions in April and also because of some excessive precipitation in some areas, we were still a little bit delayed, nowhere near what we saw in 2019, but things were delayed and because of the cool temperatures are overwintering craps, both annuals and perennials. We're behind schedule at this point in time. So again, it probably could have been a lot worse than it was, but it did cause some problems. It did cause some, some damage to some of our perennial crops is about in terms of precipitation for last year. This is an accumulating so same timeframe, the beginning of April through the middle of November. And what you're seeing here once again for Lansing, this one is a little less representative than the temperatures be, changes. But again, remember that this is Lansing. The green line here is the actual observations of precipitation on a daily basis. And then the brown line here, that's the normal, what we should see in terms of normal soft, the slope of this line is greater. Of course, it means that we're wetter than normal and vice versa. And you can see at least here for the Lansing site, a couple of areas of heavy precipitation accumulation. One in the middle of May where he could see the again the steep line here. You can also see that happen at the end of August into early September when we had another period of consistent wet weather. And that was in-between that was for much of our mid summer. You can see that the line is actually mostly trending. The slope is below the normal, so a little bit drier than normal in this part of the state. But in contrast to what we saw for temperatures, again, this greatly dependent on where you were. Northern parts of the state consistently had above normal temperature stirring most of normal precipitation rates during most of the growing season. And by the middle of May, as you see here depicted by our long-term Palmer Drought Index. And this is up, this is a long-term climatological index looking at basically three to six month periods of excess or deficit precipitation. You can see that virtually all of Michigan and much of the Northern corn belt here. With dark greens indicating surplus conditions. And some of this as a leftover from the very, very are abnormally wet conditions back into 2019. 2019, again, for Michigan is the wettest year on record on average. So a lot of surplus water was still left over from especially from the fall of 2019, it shows up here, but also because of that heavy precipitation I just noted out in the the glass graphic that you saw in terms of temperatures during the summer. So now we're looking at June, July, and August, really the core of our growing season. You can see a lot of warmer colors, especially across northern parts of the Midwest. So above normal temperatures, generally from one to as many as five degrees above normal for the summer, warmer than normal conditions over most of the area. And actually transitioning to a little bit cooler than normal as you go southward towards the Ohio Valley. In terms of precipitation, again, it dependent on where you were the actual totals here for the June through August period or on the left-hand side. And then it's expressed as a percent of normal on the right hand side. And so as you can see, much above normal precipitation rates, northern part of the state and northern parts of the region. But it right out as you move southward and you can see some areas here, especially as you get down towards Northern Indiana and Ohio, and then right along IAD, westward all the way out into Iowa and Nebraska, you can see an area that really missed out. One in particular, I'm going to show this again and which is, which is interesting to note, we had the formation of some really severe, significant drought conditions in western Iowa during the 2020 growing season. I also drier again is and this is, of course this is a key area production area in, in the corn belt region here right along IAD, but especially for western Iowa, that that was an area that just was repeatedly missed and had severe drought stress for much of the year. In contrast, a lot of the rest of the corn belt actually, they had enough moisture a lot them enough water to get them through the growing season. But that that was one area in particular that was that dead definitely have negative impacts. Here's the US Drought Monitor as of the beginning of September. And you can see the southern part of the state because of what we just saw is in here either abnormally dry or the D1, moderate drought, but it was limited once again to the Southern couple tiers of counties. But as you go westward here, note to that area that we just depicted, including some D3 and had been a while since we had seen extreme drought reported in the Midwest. But, but western Iowa definitely had it last year because of, again, a much, much below normal precipitation there. Also note, and this is still an issue there though. There was the development of drought conditions over many parts of the Great Plains during, during 2020 that has continued on to the present and it's certainly a concern now as we move into 2021 growing season and what am I talking about? Well, a lot of the High Plains. And, and it's it's actually filled in since then, but some of these areas have been drier than normal for, for some time. Now, scenario to watch here as the growing season begins this year. Couple of interesting Mao column, meteorological, climatological tidbits but are certainly worth mentioning. 2020 for the Northwest Atlantic hurricane season was the most active on record. 31 storms, 31 of those were named. And just well, what that's a new record. There's never been that many. We went completely through the regular alphabet, 21 named storms and then the no ahead and the National Hurricane Center had to go to the Greek alphabet to fill in. We've never had that many storms. There were 13 hurricanes, six of which became major hurricanes. Again, just off the charts in terms of frequency, it turned out to be the fifth costliest hurricane season on record that I guess that's if there's anything positive to be said about that, at least it wasn't as bad as it could have been. But the reason I bring this up is that two of these storms actually had an impact on the Midwest. And that's, that's pretty unusual for us here in our part of the world. The first one was a tropical storm crystal ball. This was in the first, basically 10 to 12 days of the month of June, and it formed in the Yucatan and then moved straight northward up the Mississippi Valley. And that's the one here I'm highlighting. Actually moved along the Mississippi and up through the Upper Peninsula into Ontario. And again, why am I talking about this? It was a tropical storm. It didn't even really was marginal, never really made it to hurricane status. On the right hand side here. Over the last 100 years, these are the tracks of land falling, hurricanes and tropical disturbances in the Atlantic. And you can see that by vast, vast majority, most of those effect the golf or the Southeast Coast of the US. And you can see very, very few pathways up here into the Midwest. While crystal ball was an exception to that, not only was an exception, it was probably a record in terms of being maybe as far Northwest as we've had one of these storms go. And, uh, and the reason I bring it up is because areas of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan had two to four inches of rain with the system. These systems bring massive amounts of water inlet of course, we've all seen that with in other parts of the US like Texas or the Gulf Coast, we rarely see that. But in 2020 we did we had a visit from crystal ball. We also had sort of a near miss from tropical storm beta. And that came in the early part of September and that move through the Ohio Valley even then, even though the centered the circulation stayed well south of us, some of the moisture with that did impact and remember I showed you that the trace for Lansing, some of that precipitation was with that storm across southern and central parts of Michigan. So something we don't see very often, not only create, occur twice during the 2020 growing season. Another one, another oddity and this one's of course is a bad one, is on the 10th of August, we had a well, just a record breaking the ratio event. Ratio is a name given to a cluster of basically severe thunderstorms that, that act collectively together in and what you can see on the radar time-lapse here down below shows very well what a line of thunderstorms in this case, they became severe early in the morning from southeastern South Dakota, north eastern Nebraska, and it progressed eastward through the state of Iowa into Northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and then later on that early evening actually moved into Southern Michigan and Northern Indiana. So this line moved over 800 miles in 14 hours. Some of the forward speeds here 60 to 70 miles per hour. And these were not your regular garden variety thunderstorms. These were all severe thunderstorms. And note that they impacted large area because again, it's actually collectively in a line together moving west to east. The wind speeds with this, we're well, we're, we're incredible. At least 70 mile per hour winds. In some cases here in Eastern Iowa, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa area, wind speeds of 140 miles per hour we're estimated. And the other problem with this particular weather event is they were over an extended period. Many of the areas influenced or impacted here, especially in Iowa, northern Illinois, and even into Southwest Michigan, had strong damaging winds on the order of 15 to 30 minutes of this. So again, it wasn't just a storm that came through and for a minute or two we had really we're damaging once this was over an extended period. And the damage with what this event was massive, especially in Iowa. Lots of structural damage house. My nephew and his wife live in the Cedar Rapids area and they're going to have to re roof and lots of damaged trees falling on cars. They they total both of their cars at the damage with this one, this event on the tenth as of January and 20 this year 2020 one was up to $11 billion, which makes this event the most costly in US history with you adjust for inflation associated with severe thunderstorms and that's, that's hard to do. So this is a big event. There was a lot of agricultural impact as well. Corn and soybean crops flattened that we're not basically not salvageable, had to be written off. So there's a lot of especially after 2019 and all the problems with that crop. There were more problems for the insurance adjusters and the growers in 2020 as well, especially in a state of Iowa. Fortunately in Michigan, the storms were weakening as they got here and the damage wasn't nearly as quite as severe was in locations to our West. So it could have been, it could have been worse. But this was a very, very unusual event for from a meter logical and climb logical perspective. If we look at the whole season in terms of heat accumulation, growing degree days, remember I mentioned that the summer was generally a little bit warmer than normal, and that's how the degree day totals ended up here as well. With about a surplus of anywhere from 50 to 150 base 50 degree day units, the exception the Upper Peninsula, where again, remember it was wetter. There was a lot more, lot more clouds. And there we've got a little bit of a deficit, but no more than 50 units. So we were fairly close to the long-term average to a little bit. Above normal for most of the state, and that was the case across the northern part of the, the, the Great Lakes region and then the corn belt with little, with deficits that you go southward into the Ohio Valley. And overall in terms of yields, really dependent on where you were, but most areas did pretty well. This is a graphic from USDA that shows the corn yields and then the percentage change over the previous year. Remember 2019 was a very, very trying and challenging year for a number but a lot of weather related reasons. But here in Michigan, you can see almost a 14 percent increase from the 2019 crop. The only, again, the thing that sticks out in the Midwest and the corn belt look at Iowa. And again to two reasons there. One, the drought and then the ratio of n. Both of those combined, they still had state yields on the order of a 186 bushels. But, but that was down relative to the previous year because the production was just down. But overall, for most of the area, we certainly did better than in 2019 and actually a little bit above or at the trend line. So overall, it worked out fairly well for most folks. Moving on then into the fall and into the winter. A few things about that. Obviously, we we've seen evidence of this over the last couple of weeks is the major changes. But our winter for 2021 started off mild. And here's that, that heat wave that we had back in the month of the first two weeks of November. I was working with many sing and Matt gammas on a project looking at dry down of corn here and head feel plots. And during that period where our maximum temperatures in some cases we're well into the seventies, whith low humidities had drying rates on a daily basis. We were looking at individual years and we had drying rates well above 1% per day. And if you add data, you look at the collective impact to that. This warm, dry period here of a week resulted in millions, tens of millions of dollars of positive economic impact because of, well, we didn't have to dry. And so if you had crop out at that point in time again, this is that first week in November. You really, really benefited from this very unusual period here. We don't get those off and we're actually looking at that right now how frequently that these types of events occurred. But economic impact in terms of that, it's a, it's an amazing thing to see that side, of course, in our favor to have those weather conditions. But for most of the early part of the the late fall, the early winter, our temperatures were milder than normal. Again, this is this is once for Lansing data. And you can see that most of the time we're on the upper part of that brown normal range of temperatures until until the last part of January. And that's when we saw a big upper air change, the last 10 day period. You can see that here with the Arctic outbreak and polar vortex. And I'm going to talk more about that here in just a second. But we started off mild and then finally hit. And until, well, there's, there's a number of numbers I've put together here, but I do want to say something about this, this polar vortex. We hear this in the media sometimes. What is this and does it make any sense? And what we saw happen here? Well, of course, the jet stream is the reason the flow of the jet stream across North America is the direct result or the direct influence of our, our temperatures during the winter, especially over week-to-week type timeframes. And for most of most of December and for most of January, that the jet stream just was not allowing the, well, the train, the transport of air from high latitudes over Northern Canada and the Arctic into the lower 48 states. And when that happens, we, we stay above normal. Most of the air masses that we were that were moving across the upper Midwest were from the Pacific and modified. And and again, the result was above normal temperatures for for loud that timeframe. Well, one of the one of the meteorological influences on winter weather, and it doesn't happen that often, but once in a while it does is something called a sudden stratospheric warming event. And that's a really, really wordy way of saying that we basically couple what happens. The stratosphere is a second, hi, the second layer in the atmosphere after the troposphere. The troposphere is the lowest layer. It's where most, all of our weather takes place. The lowest, essentially about 10 miles, nine or ten miles or so at lowest layer. That's, that's what really matters to us and, and, and get most of our weather occurs in that. But the stratosphere is the next layer and generally does not influence or have much of an influence on our our weather and climate down at the surface, but this is an exception to that. And at certain times we see a warming of the stratosphere occur again in the second layer. And it actually, when that happens, it couples the circulation in the stratosphere, the second layer with the circulation down below in the troposphere, and that in turn influences the jet stream. The jet stream is essentially the upper half or so of the upper third of the troposphere. And that's the key one here in the mid-latitudes, absolutely essential. It describes our day-to-day and week-to-week. And when that coupling occurs, many times we get a, the jet stream flow. Instead of being mostly west to east horizontal meteorologist say, move things right along, we get these big ridges and troughs or bends in the pattern in the jet stream. I'll show you that just here in a second. But we get the transport of air either from the Arctic or, or high latitude areas. And we can also be under a big ridge where we get the transport of subtropical air. So it can go from, again, being near normal or even a little bit milder than normal to either being much below or much warmer depending on where you are relative to these, these events. So the stratospheric warming events Act a couple. Those two layers. And why is it important? Well, statistically we know we're looking down out of an image at the North Pole after these stratospheric warming events occur. And they're typically they occur over a several day period, maybe a couple of weeks. But after after those events occur, maybe another week or two down. In time, we, we tend to see in some parts of the world, like Northern Europe and Northern Asia, we tend to see much colder than normal conditions. The same is also true over portions of the central and eastern part of the lower 48. You can see milder than normal here over Northeastern North America and Canada. But these are listed in, again, these reflect those changes in the jet stream in the troposphere, the lowest layer of the atmosphere that not always, but tend more often than not to happen. Well, back in the middle of January, we had a sudden stratospheric warming event. This is from a blog by the name of a guy, by the name of Judah colon, an atmospheric scientist who works for the ADR company and does a weekly update, does a really nice job of this. He's a specialist in this particular phenomenon. And he broke it down, as you can see here in yellow, there were three sort of pieces of the stratospheric warming event that took place over about a three or four week period. And ultimately the last one here, the third one is the one that changed the jet stream over North America and lead to this introduction of unusual or abnormally cold air into the lower 48. And that's what you're seeing here. There's two maps, one of them and the one on the left is the important one. You're looking down at the North Pole with this and we're looking now at jet stream flow over the Northern Hemisphere. And again, you can see where these, all these lines are. That's the really to the core area of the jet stream. Where to time of the year where this the jet stream is as far equatorward or southward as it goes in the northern hemisphere, it will begin to shift and contract and go back up north for as our seasons change in spring goes into summer. But right now it's about as far equatorward as we go. And if you look at North America here, which is on the lower part here, very, very interesting pattern. And this big cyclonic upper air low here that's over southern Canada. That is a piece of the Arctic. And that's what's so bizarre about these events. We, we don't, it's not, it's not really canadian. This feature actually had its origins up along the North Pole. Even you could even argue into Siberia on the other side and then migrated across and then ultimately ended up here at Southern Canada. That rarely happens. And that's what's so special about these are so unusual about these warming events that we see. And this one again ended up in Southern Canada, basically generated its own cold air masses one after another that came down from, from Central and Southern Canada into the lower 48. It is the direct, again, cause of all of this cold air over the last couple of weeks. Maybe that mean temperature departures from normal here for the last 30 days. And I guess if there's any there's a couple of things. Again, it could have been worse if you look at the positives and negatives about this. But the coldest air with this definitely was over the Great Plains and over the central part of the US. Michigan was on, sort of on the eastern periphery of it. And there's still another factor there and that's the great lakes or the Lake Michigan especially I'll show you that in just a moment. But this lead to extreme temperatures and as we've seen in the media here, some of the couple of the air masses with this or were, were historical. Especially over the southern plans and what we saw in Texas and Oklahoma. And then all across the South, temperatures that are rarely, rarely ever observe there. And of course now we see all the problems associated with that because it is so rare. But this is again, what they, when they talk about the polar vortex, it is literally a piece of climate that occurs up at the end, the ice cap in the polar region. That's translocated unusually two mid-latitude areas, and that's, that's what we're seeing. And we are at the very, very end of it. I'll, I'll show you that in just a second. A couple of other things to just some amazing footage on the left-hand side here. This is from the eighth of February, a visible satellite looking down at Lake Michigan. And you can see a couple of things. One, you can see the snow cover that's already fairly extensive at that point in time. And then the open water of the lake. You can also see some of this wider, That's actually the formation of ice that has occurred rapidly. And that's going to be the next image. I'll show you the growth of ice here. We went from virtually no ice on the Great Lakes now to above normal, just an period of a couple of weeks. More importantly, if we look at air temperatures and these are surface temperatures on the eighth of February. So looking back a little bit more than a week when the first really cold air mass, you can see all sorts of minus 20 is minus 25s here with air underneath it was right under the middle of that that that upper air feature, that cutoff flow that I showed you and it poured into the lower 48. The coldest air here is just across the border at that point in time. And this air mass actually ended up going straight Southward. That's the one really cause problems for the Southern Great Plains, including Texas and then all all along the gulf for several years. That's that's the ER mess. It made it down that far. So again, literate for them, it's even more rare than it is for us because they're further South and further away from the source region of this. But the other thing to note about this, look at Michigan here and look at the difference in temperature. West to east, where we've got minus twenties on the other side, a lake in Central Wisconsin. And then temperatures here, this was actually a forecast product and it turn out not to get quite that cold, but temperatures are clearly at least 20 degrees warmer on the other side of the lake. And again, that is that is courtesy of all of this relatively mild water. Here. Water temperatures in Lake Michigan were on the order of the mid and upper 30s when this happened. You can see the clouds here. Basically it's instantaneous convection is at frigid, air, goes across and absorbs energy and moisture and then moves from west to east. But we were moderated and buffered by Lake Michigan. It turned out that superior already had some ice on it in the West. And so the western part of the Upper Peninsula was not and that shadow, but most of the lower peninsula was a lot of the wind here when flow is generally west to east. And so a couple more. Again, just show the, what happened is the cold air. Intent or cold-air moved in for the longer haul. Some cases more than 40 inches of snowfall fell in this area with some of that was lake effect that we did. We did have a lot of heavy lake effect in certain areas. And in terms of percent of normal, especially as we go to our south and west across the corn belt, you can see 300, 400% of, of normal snowfall. So what had been a winter with abnormally low snowfall quickly became the exact opposite with this, with this huge change in weather. And now we have, I think you could argue one of the more extensive deep snow packs across the upper Midwest and the Great Lakes that we've seen in several years that's here in the middle. Although again, lake effect snowfall this winter because of all the mild ear, has been unusually white, unusually low. And some parts of Michigan before the onset of this, we're less than 25 percent of normal snowfall. A lot of it again, because of the lack of lake effect snow fall, but we've we've made up for lost time in the last couple of weeks. And then one last one. And this one if, especially if you're interested in perennials and, and an extreme low temperatures, this is an important one. On the right-hand side here, this is literally hours hold. These are extreme minimum temperatures so far this winter. Most of these occurred in the last several days. This graphic again depicts an illustrates how incredible the lake effect like moderation was. And these are extreme law. We have some of the state here back on Tuesday and Wednesday morning, we had the lowest temperatures in the winter in central lower Michigan, Southern lower Michigan. Most of those are on the order of ten to 15 below Fahrenheit, but near the lake. And it's not just the Western side, but also bordering Lake Erie. And here on, on the, on the eastern side of the state. Or low temperatures have been above 0. In some cases here we had there, even in the low teens, that's the lowest. It's been just, just remarkable influence of the water. You can see that here, especially in West Central and Northwestern lower Michigan. Again, some of these, the extremes so far have only been in the low teens versus the other side of Lake I I I didn't plot was constant here. We will, but many of those were in the other order of 25 a law. If you're into the records of the climate part of it. Note here up and Iron County, Tom is old stomping grounds here. We hit we had a minus 46 that I'm a sock that was on the seven the morning of the 17th. So incredible variability across the landscape here with those extreme minimum temperatures. But, but the lakes makes such a huge difference. A couple of things here, I want to move on quickly. We could, we could dwell on them on the winter and the meteorology. And I'll get back to the very end. But a couple of trends I think that are important to put some perspective here. What you, some of what you've just seen, Michigan is getting wetter and still continues or warmer and wetter. That's the general tendency or direction trajectory that we're in. These are annual temperatures average of course, of the year for the state as a whole. And you can see that on average, we're about two degrees Fahrenheit, warmer now than we were about 50 years ago. But couple, couple other things. You can see here, that blue line here, that's a nine-year moving average. I've, I've put in with the data to, to look at some of the, the longer term decadal type of trends, it's leveled off. And so at least in terms of annual warming here, for the last decade or so, we've sort of been stuck or at a sort of a level area. A lot of the warming that occurred back in the eighties and nineties, and it has at least head is temporarily slowing down. The other thing you could note here, there has been a little bit more variability from year to year. We've had some very, very much some of the warmest years on record or the warmest years on record in the last decade. But we've also had some unusually cold or cool years, 2013 in particular. So variabilities, another issue that's, that's important with, with these temperatures. It's also important to note that most of the warming has occurred in the cold season, in the winter, December, January, February, until a little bit lesser extent in the spring and the fall. And at night, we've had our minimum temperature is increasing more rapidly than our maximum temperatures I'll show in a day blend just a moment. But looking at the growing season here, this is looking at the months of April through September. You can see a similar pattern with these with slowly warming temperatures, especially over the last 50 years, but some leveling off during the last 10 to 15 years, just like what you just saw. If we look at degree day units. And this is for a site here in West Central lower Michigan, here at Big Rapids, which is representative. This is not quite as long, a period 9800 through last year, but these are both annual totals in the lighter red and then growing season total. So again, we've defined is May through September. You can see fairly straight line. So at warming is not necessarily translating into higher degree day totals. Little bit, little bit different than what we might expect, but they've been, they've been fairly level. There's more nuance here that I'm going to show you here. If we look at maximum temperatures during the summer, so June, July, and August, and we look at that trend. You can see it's, it's also relatively flats, long-term, little bit of an upward trend, but, but generally still sideways or flat. So the maximum temperatures, there's not much going on with those minimum textures. You remember I mentioned that, that there's been more warming at night with a minimum temperatures and it has this, this is a really good example. Those so same area. This is a, this is the climate division, the west central part of the state. So about an eight or nine County area, but it's representative. You can see clearly that especially over the last 50 years, there has been a warming of our nighttime wear minimum temperature. So the addition, all that additional temperature, mean temperature that we're going up, most of it is, is the Min taps and in a night. Another important one. What about extremes? And here we're looking. This is four for three rivers down at St. Joe County through this N4 for Eric, but it's it's a relatively representative for actin again, and this one goes back to 920. But here we're looking at bright red number of days each year at 90 or greater, the brown 95 or greater. And then we're thrown another one in here that you don't see very often, but I think it's also important economically. The number of minimum temperatures that stay above 70 each night or at or above 70. So warm nights, what's happening with those? And as we look at this, it's actually, the long-term trend is downward. So we've tended to have fewer extreme events with time. There's in some series and Michigan, we see a little bit of an increase here over the last ten years or so of the high temperature events, but that the long-term trend is still downward. The Clearly the peak decade of all these extreme max temperatures. It's back in the 1930s and that's still the benchmark, greatest frequency that we have for those. But the other interesting one is if we look at the blue, there has been an increase in those warm nights. And many of those, I'm sure many of you have heard about this, but there is a correlation with the number of warm nighttime temperatures at or above 70 degrees and reductions in some of our annual crop yields, particularly corn and soybeans. It's a bad thing in parts of the central US, especially as you go south in the Ohio Valley and the Lower Mississippi Valley, middle Mississippi Valley, there are, there are definitely distinctive statistical links between drop-off you'll drop offs and the number of these events. So it's, it's using, the crop is using resources at night, of course, when there's no light and it's basically just a loss. And that's, that's one that we need to take. We need to, especially given what we saw with these trends to keep an eye on. But we're worth the northern part of the region and we really aren't. It's the same with the same threat or same vulnerability that they are in areas further south. 11, last thing to seasonality is changing. This is a graphic. Once again, it's freelancing, it's representative. What it's showing is that day of the last freezing temperatures of the springtime or the spring season that's in black here. Those are getting earlier with time. The first freezing temperatures of the fall up here in red, getting later. And what we have in the middle here in green are frost-free growing season. It's increasing because of both of those. There's longer a longer period on the order, two to three weeks more now than we had just 50 years ago. That's a pretty big change. So we have a, that's a positive thing. But as you saw, the degree days, there's not necessarily so much in terms of extra degree days there. It's just that we have a longer frost-free season. Couple of things really quickly. I mentioned Michigan's getting water. Here's the precipitation trend with time. Ten to 15 percent more precept. Now that 15 years ago, three to four more inches of water on average doesn't mean every year, but that's the average. That's a lot of water. And and I think my opinion is, what about those extreme maximum temperatures we're seeing in other parts of the US, like the Western US, we're seeing major spikes in the number of those events, I think. And there's a lot of evidence to support this, that the additional water in the landscape, especially in the warm season, it takes energy to evaporate water. And that's actually what's preventing our maximum temperatures from increasing more than they would be otherwise. There's a clearly there's clearly an effect of having this additional precipitation. And as you can see from the graphic here, really this upward trend, it shows no signs of, of, of dissipating or abating. We're still on an upward trend. Dod additional precipitation is both because of more what days and that's what you see here. For three rivers increase. The light green here is the fraction of days with measurable precept. We're also seeing increases in the number of multiple wet day events. What day is it follows? Both of those are increasing. So again, part of the additional precept, we are also saying at the, or the other side, consecutive dry days. This is if you're an irrigation management, this is, this is an interesting one. This is looking at three rivers and St. Joe County, two different periods here. One mid-century last year and then one more recent. But because of the additional wet days that the strings of dry days that we have to deal with in-between, the length of those is decreasing and that's what this basically shows. It's not a lot, but it is, it is definitely discernible. And so by a couple of days that the dried a string that we would expect to see now is shorter than what we have observed in the past. We're also seeing more heavy rain events are more precipitation per event. That's what this graphic, the red circles are all increases in the number of heavy events that's increasing as well. Another one looking at the 1% heaviest precipitation, extreme events are increasing. That's what we saw evidence of that, a whole lot of evidence of this in the last couple of decades. And an important one here, this is looking at the June, July, and August period, the summer. Here's the preset and you can look, it's it's flatline. So there's some seasonality what the precipitation trends in Michigan as well. Most of the increases in precipitation had been in the winter, spring, and fall, not as much in the summer. There's a little bit of an increase, but it's not nearly as much as what we're seeing and other seasons, but more importantly here for agriculture, the red here is a standard deviation copied at the variability. Look what happens here over the last few decades. As we get an increase in the number of wet days heavy events, the variability is decreasing. And that's a positive thing. It means that, that the rainfall is, is essentially more reliable or more consistent than it has been in the past. And that's that's one way we can't. It's hard to put a finger on, but I think it's a very, it's a very positive thing. Doesn't mean we won't have problems with lack of water. We've seen that, but it does mean, and that's what this graphic here shows. We still have droughts, but on average, you're looking at the palmar z-index here, which is a drought index. They're less frequent and less severe on average than we have had in Michigan in the past. Again, that's a positive thing. We also have, of course, too much of a good thing. And this is looking at April and May precipitation totals. I mentioned that a lot of the increase has been in the cool season. Well, unfortunately, part of it, as we saw with an exclamation point In 2019. This is also true for the fall. Unfortunately not quite as extensive or not quite as large a trend here, but look at this increase, an extra one to two inches on average that we're seeing in May and June versus what we did 50 years ago. And again, that's the timing is obviously poor or bad for that. So again, you can, you can have too much of a good thing. As we saw in 2019. We've also seen increases in humidity. The water vapor in the air. That's not surprise given all the additional precipitation, It's also the raw material for more precipitation. So all those things are increasing. If you ask why? Well, it has to do with the jet stream and the patterns that cause precipitation. Midwest and the patterns are more conducive for that. I think Bruce, I I'm I'm behind here, but do I have time just to do a real quick wrap-up flow? Yeah, Absolutely. Jeff, we've we're towards the end of the week, so we're in good shape. I'll just get probably too carried away with these things, but do want to talk about where we are because we are right now at a transition. In terms of the meteorology. I showed you the, the problem here, the last two weeks with the polar vortex, et cetera. Well, It's on its last legs, or at least it's not on its last legs, but it's going to move somewhere else. I think that's just as important here. And what I'm showing you right now is a, a forecast for next week for jet stream pattern across. And note that there is no polar low here in Southern Canada and the northern US anymore. And that our jet stream flow forecasts for that timeframe is forecast to be much more west to east. Right hand side here. This is for the 22nd through the 27th of February. These are temperature anomalies at the surface. And you can see we've, we've got some warmer colors here. So it's actually forecast to be or the, again, this is the numerical forecasts guides certainly suggest a major warming. We're going to see that beginning on Monday in Michigan. And actually a thought for several days for a lot of the state will be above freezing, probably not in the far northern part of the state, but we might even push 40 on Tuesday in a couple spots, but certainly we'll see some melting finally, in some far AFTRA and extended cold front period. And again, the, the issue is here that the jet stream has changed. If you're again into the meteorology, we look at this map here. This is looking at a large area, this blue area here that's out in the middle of the Atlantic. And also this trough here, that's the, that's the remnants of the polar vortex. It's again, few thousand miles to our east. That's fine. Good riddance. It's on its way to Europe. But that's actually what's left of that, that unusually cold area, if you're wondering where it went. Well, that's that's where we're going to get air from the Pacific here at least for, for the early part of next thing. Now on the leading edge of that warmer air, we will see will see some lake effect snow fall here today, especially in Western lower Michigan. In portions of the Upper Peninsula, there's enough ice on superior where the amount of lake effect There's actually reduce a little bit. But tomorrow should be a nice day for most of the state. And then on Sunday, the first warmer air that's not arctic origin moves towards us, will cease of snow on the leading edge of that, beginning in the afternoon and into the evening and probably in their early Monday, we could see a few inches that especially central and northern lower, maybe maybe some, some places get four or five inches so it will be shovel snow in it. But then of course it's on the leading edge. The good news is, is then we see much milder temperatures on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, and then a little bit more colder, but seasonable, cold air moves in for the latter part of next week. Not not anything outrageous like where we've been. Precipitation totals here actually, nothing to write home about most serious quarter three tenths of an inch. Most of that will be on Sunday and it early Monday here over the next week, the rest of the time. And so lake effect that they will be generally dry, mid, mid-range. Same, same general pattern here that we're seeing from some of the other. Well, the forecast guides I just showed note here over North America, we've got traffic out over the western part of North America, ridging over the Southeast Michigan sort of in-between those two with mostly west to east that will allow some colder air here, but also probably a fairly active storm track through the Ohio Valley. That's something very typical of Flaminia, which is what we have right now. And that is sort of the theme that we're looking at for the extended time range into March and actually into the spring, looking at our at least for the medium range, six to ten days, almost identical to this, but through part of that first week in March, milder than normal temperatures has been a while since we've been able to say that, and also above normal precipitation totals. So at least for the precept here, this is a classic La Nina type of, of upper air pattern and weather pattern. And it influenced our March, certainly our new long lead out looks for March. If we look at our sea surface temperatures here, these were yesterday, we can still see the blue area here cooler than normal sea surface temperatures. That's the classic signature of La Nina, cooler than normal water in the Eastern and Central Pacific. That is, it's not as extreme as it was a couple of months ago. It is moderating. And I'll show you that the outlook is for conditions to become neutral go back to more normal here as we move toward the end of the spring, There's one other area here outlined in red. And then this is one to keep an eye on. And during La Nina years, when we have the formation of warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the Northern Pacific. It's a little bit of a flag. We have associated this and I only want to bring it up, but it, it's, it's, sometimes we see this with drought forms in the central part of the country and actually has to do with the, the upper airflow here. And while the reason I've actually had a couple of people asked me about this and varies. This is the this is the feature that we had in 988. If you're been around my old card, you're like me and remember, 88 is definitely the most significant drought that in 2012 of our generation or the last couple generations. But in 988, we had a very strong La Nina event that continued into the spring with very, very abnormally warm sea surface temperatures here. And it was one of the causal mechanisms leading to the wood that year and 88, what turned out to be the worst, probably early season drought that we had seen, certainly in 50 years in the Midwest. But that said, it's against something. To keep in mind. We do have warmer warmer than normal water out here. It's not nearly as extensive, nor is it as warm as what we saw in, in 988. So again, that's history does repeat itself in these things. But I think in this case it's, it's very likely that it won't, but it is something to watch. De la Nina is forecast to generally to dissipate here over the next several weeks and into the that's what you see here. The blue line here is forecast of of consolidated forecast. For sea surface temperatures and that Pacific, if it's negative, of course it's still anemia. If it's more than if it's positive, it's, it's generally an El Nino and a neutral sort of in the middle. But what you can see from the Outlook and then the probabilities are here for the season. And the right hand side is that the La Nina is forecast to gradually weaken towards the spring in the summer and be neutral here for the summer. So again, I think that that that's the important thing right now, and I think that that's probably the best bet. And then looking at the new lonely that looks here at the very end, you can see for March, the new outlook does call. It, bumped us into a little bit milder than normal mean temperatures are in that category. What are the normal classic classic La Nina? That's why that is. So the, the mild or the normal temperatures here will result mainly of the numerical forecast guidance. Not so much the alanine yet, but this precipitation pattern is, is what we typically see in the spring with with anemia and then for the three month March through May, similar, very, very similar conditions. Little bit Min normal to above normal temperatures favored, but also for the increase precepts signal. So more of the active storm track, that's going to be an issue. I'm sure as we start to think about the growing season. At least that's what these outlooks are suggesting right now. And then for the growing season itself, I won't test your eyesight here. But what they do suggest for the upcoming season as we go back to neutral and so cycle warmer than normal, mean temperatures across a lot of the corn belt and the Great Lakes. And at least for the early to middle part of the growing season, maybe above normal precipitation. But you can see by mid-summer that goes away to the equal chance a scenario and then continuous for the remainder. So there is continuity in these, but it does suggest at least for the early part of the season, once again, maybe what are the normal that, that could be an issue as we approach, it sees a map up and I again, apologize for going a little bit over here. Bruce, I don't know if there's any time for any questions or comments, but thank you very much for your attention. And I'm hoping wishing best of luck and hopefully will enjoy some more normal temperatures here within the next several days. I'd be good. Eric. Eric has got the survey link in there at the end, so thanks Jeff for the update in there. I think we've got a couple of Q&A questions. I'll try to get those copied for you to get them sent out to you that it's blank and answer those in there too. So what we'll do now is we because of the RUP credits, we close out these sessions each time and so that we can record the log there for folks that have been involved in the on the on the call there. So please fill out the survey. The survey is the in that chat, in the chat screen, that link in there is the link to get to the RU piece helps us also understand if the program met your needs. And so again, thanks Jeff for setting the stage for us for the rest of the discussion today and by our weather and, and perhaps as your farm ready for extreme weather. So we're, we're about to close up this session and we will see you back at the next one hopefully. So. Thank you for participating. Eric, anything else that I need that I forgot to mention? The survey link is in there for those of you who have been having issues with that, go ahead and either click on the hotlink, copy it into a new web browser, or if none of that works, send us an email and we can help you. We have those questions. I think we've gotten captured, so I'll send those to Jeff. Thank you very much, folks for participating and we'll close this out here shortly.

Print

Print Email

Email