A Spartan comeback of the seed kind

The barley fittingly called Spartan, created in 1916, is making a comeback in light of increased demand for locally brewed beers in Michigan.

In 1916, Michigan State University (MSU) plant breeder F.A. Spragg created a new variety of barley fittingly called “Spartan.” The cultivar — a cross between Michigan black barbless and Michigan two-row — had higher production capabilities and superior quality compared with other commonly grown barleys. By the late 1950s, Spartan barley was found on farms around the country.

The passage of time, however, brought new advances in plant breeding. Eventually, Spartan was surpassed by barleys of even higher quality and yields, and this once-commonplace grain was relegated to the annals of agricultural history. The seeds were locked away in a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) gene bank in Utah, one of a number of facilities established to preserve the genetic diversity of the nation’s field crops, for more than 60 years. Now, a team ofMSU researchers in the northern region of the Upper Peninsula have set out to resurrect Spartan barley in light of increased demand for locally brewed beers in Michigan.

Barley has been produced around the world since the foundation of agriculture nearly 12,000 years ago. References to the grain have been found in the writings of ancient Greece and Rome, on 4,000-year-old clay tablets in Iraq and in Egyptian hieroglyphics. It's long global success can be traced to its versatility: barley contains eight essential amino acids and is used in bread, livestock and fish feed, as an algicide and, perhaps most notably, in beer and whiskey production. Barley is a key ingredient in the malting process, in which the starches of cereal grains are converted into sugars by soaking them in water and then drying them in hot air. Combined with hops, yeast and water, it is one of the four essential components of almost any beer.

Since the late 1990s, craft breweries have proliferated rapidly in the United States, driven by consumer demand for beers made with local ingredients. Today, more than 2,300 craft brew businesses are in operation around the nation, representing more than 104,000 jobs and a nearly $20 billion industry. Expansion of operations has invigorated grower interest in producing the necessary crops — hops and barley. A new 400-acre hops farm, MI Local Hops, is planned in Williamsburg, Michigan, that would double the state’s hops production.MSU AgBioResearch scientists and MSU Extension specialists are working to help growers meet craft brewers’ requirements around the state.

“We’ve been working with barley for the past 10 years,”said Ashley McFarland, center coordinator for the MSU Upper Peninsula Research and Extension Center (UPREC) in Chatham. “A lot of craft brewers and distillers want to source their grain here in Michigan, and we’re helping farmers produce a crop that has the level of quality that malt houses need.”

As researchers investigated the opportunities that malting barley represented for Michigan farmers, one brewer reminded McFarland that MSUhad once produced its own barley variety: Spartan barley.

“Everyone gets excited about the prospect of having locally grown barley in their beer, and it doesn’t get more local than a variety pioneered byMSU,” McFarland said. “We wanted to bring it out to the center to start testing it, to determine if it was something growers could use.”

Because Spartan barley was no longer grown and no samples remained in Michigan, McFarland’s team reached out to MSU AgBioResearch agronomist and plant breeder Russ Freed for help. Freed’s long experience in the field of plant breeding, developing varieties of oats and wheat, yielded many contacts in the industry, among them staff members at the USDA gene bank in Utah.

“The gene banks are important repositories of genetic diversity,” said Freed, professor of international agronomy in the MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences. “There are a lot of varieties, like Spartan, that go out of production but might still have characteristics that plant breeders want for new varieties. The USDA banks allow them to go back and search those out.”

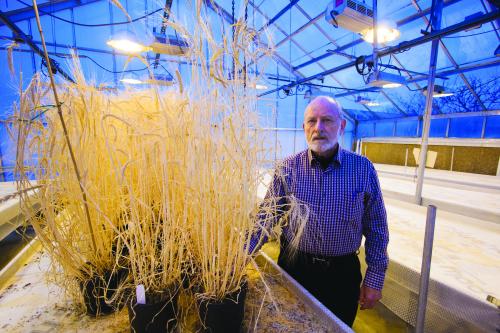

Freed received five grams of Spartan barley seeds, which he planted and successfully grew in greenhouses on the MSU campus in East Lansing. The seeds of those plants were sent to UPREC this past spring for planting and testing in the field.

“We have made significant progress since Spartan barley was developed into a high-yield crop. The thing with microbreweries is that they make smaller batches of beer, so they don’t need the large, standardized quantities of malting barley that the big brewers do,” Freed explained. “Microbrewers like to have something with a local flavor, with local significance. They like the idea of having diversity in their product line.”

The staff at UPREC, led by MSU assistant crops researcher Christian Kapp, will test Spartan to see if it is a viable crop for microbrewery use.

“When Ashley [McFarland] told me MSU had released a barley variety called Spartan back in the teens, I thought that was really cool,” Kapp said. “I’m excited to see how it does in the field.”

Kapp has been working with barley at UPREC since 2004, with a specific focus on malting barley since 2011. This year his team planted Spartan during the first week of May. During the intervening months until harvest time near the end of August, they will observe the plants and be on the lookout for the ideal characteristics of a good barley crop.

“The traits we’re looking for are ease of harvest, a strong stem and grain heads that stay intact,” Kapp explained. “If the heads break, the seeds can scatter and be much more difficult to collect. These are all things we need to investigate because we need to make sure this is a good fit for farmers and brewers.”

The initial quantity of seeds is too small to create a comprehensive picture of Spartan’s potential, so Kapp’s team will collect this year’s seeds and use them to plant an even larger plot next year.

“It takes time to get a production-sized plot established,” McFarland said. “Potentially, we’ll be able to start full variety trial work in 2016 or 2017.”

Michigan growers and maltsters are eagerly awaiting preliminary results. Carl Wagner III, a lifelong farmer and 2011 MSU graduate, is the founder of C3 Seeds, which supplies farmers with seeds for a variety of crops.

“When Ashley [McFarland] emailed me about revitalizing Spartan barley, I got very excited,” Wagner said. “Looking at the history of seed development, anything from Michigan State is right up my alley. There are a lot of questions yet on the agronomic side of this, but there are a lot of opportunities, too.”

Brew business takes interest

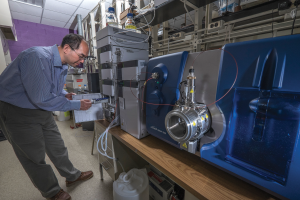

The Pilot Malt House in Byron Center was founded in 2012 to provide high-quality malt to Michigan craft brewers. McFarland works with the business on a weekly basis, exchanging ideas. She pitched the idea of Spartan barley, and the staff jumped at the possibility. Ryan Hamilton joined Pilot Malt House as a maltster the year after it was founded and has since seen the company expand its malt production fourfold.

“When Stroh’s went out of business, malting barley production in Michigan essentially ceased,” Hamilton said. “We lost a lot of the knowledge that was passed down, a lot of that heritage, and Spartan is from that earlier era. As an heirloom variety, it’s significant. It would only help our business and our customers to have a barley grown here, and the fact that it’s from MSU and the 1910s only adds to its mystique.”

Most barley now grown in Michigan originates in North Dakota and central Canada, regions with different climatic and environmental conditions. Hamilton said he hopes that Spartan, with its roots firmly in Michigan soil, will have the genetic fortitude to thrive where other varieties presently struggle.

“The varieties we get from out west perform differently here,” he said. “In Michigan, we have more concerns about fungal infections and higher moisture levels than they do, and we get big rainstorms close to the harvest. Even if Spartan doesn’t turn out to be viable as a commercial variety, bringing it back will allow us to breed its best attributes, those suited to Michigan’s climate and soils, back into our barley crops.”

If successful in the trials, Spartan barley stands to help not only Michigan malt houses and craft brewers but also the agricultural industry of the U.P., where growing options are limited by long winters and relatively brief summers. Under McFarland’s coordination, the team identified barley as one of a number of small grains and forages with potential for the northern region. Barley test plots at the center have already shown promising yields. Add the appeal of the barley carrying the MSU name grabs the attention of growers, malt houses and craft breweries.

“We’re in the early stages now, but a lot of people are excited to see it,” McFarland said. “To be able to have a Spartan beer made with Spartan barley at a Spartan tailgate — that’s something worth pursuing.”

Spartan barley holds a unique place in the annals of an ancient crop, both for its historical use in barley production on a national scale and now, as it experiences a resurgence, for the potential it holds for Michigan agriculture and craft brewing.

“It’s more than just an heirloom variety,” Kapp said. “I mean, how cool would it be if we could resurrect Spartan barley and bring it back after over 60 years? From my perspective, that’s a major appeal. Let’s dust it off and see how it does out in the field.”

Print

Print Email

Email