Nature reserves aren't protecting pandas, research shows

Panda habitat is being destroyed quicker inside the world's most high-profile protected nature reserve than in adjacent areas of China that are not protected.

The way to panda extinction may be paved with good intentions, a Michigan State study published in Science shows.

Panda habitat is being destroyed quicker inside the world's most high-profile protected nature reserve than in adjacent areas of China that are not protected. Moreover, the rates of destruction were higher after the reserve was established than before the reserve's creation, says Jianguo Liu, an associate professor of fisheries and wildlife at MSU.

"Some people may think about human destruction intuitively," Liu said. "Our research integrates humans into the equation because human destruction is the most critical factor in the fate of the pandas. If biodiversity cannot be protected in protected areas, where can we protect biodiversity?"

MSU researchers and their collaborators in China did a unique 32-year analysis of the Wolong Nature Reserve in Sichuan Province, southwestern China. Using both data from a recently declassified spy satellite and NASA's Landsat satellites as well as information about the human settlements in the preserve, the research team paints a vivid picture of why years of protected status have meant less panda-friendly living in the reserve.

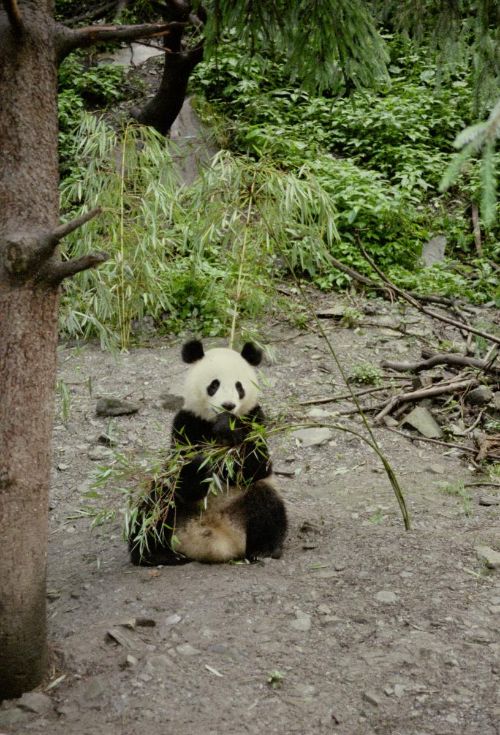

Only about 1,000 giant pandas remain in the wild. About 10 percent of these live in the Wolong reserve. Created in 1975, the reserve is a flagship effort to preserve and protect biodiversity in important natural regions - a movement that has led to nearly 9 percent of the earth's land surface being designated as protected.

Panda preservation has been a highly popular and publicized effort. The reserve has received considerable financial support from the Chinese government and international organizations, such as the World Wildlife Fund.

But, according to the recent study, it's not working.

Liu and MSU Ph.D. students Marc Linderman and Li An, along with Zhiyun Ouyang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and Jian Yang and Hemin Zhang from China's Center for Giant Panda Research and Conservation, assessed the rates of change in forest cover and giant panda habitat before and after Wolong was established as a nature preserve.

The paper, "Ecological Degradation in Protected Areas: The Case of Wolong Nature Reserve for Giant Pandas," points out that protecting biodiversity takes more than putting up a sign.

To survive, giant pandas need plenty of forest canopy, elevations that allow for comfortable temperatures, and slopes that are not too steep to be uncomfortable. Liu's team combined these criteria to define desirable habitat, then mapped it with satellite and remote sensing data. The resulting maps show, over time, prime panda real estate being nudged out by areas of human habitation.

"Panda habitat is not only being destroyed and fragmented, but it's the high-quality habitat that's being selected by humans," Linderman said.

Liu explains that the towns and settlements have thrived in the Wolong Reserve. The local resident population there has increased 70 percent. This is partly because much of the population is ethnic minority and exempt from China's one-child-per-family policy. But it also is because of shifts in economic opportunity. Establishing it as panda heaven also has drawn people to the spot. Tourists stay in hotels, eat local products and buy local souvenirs.

"Tourists don't think they have an impact on panda habitat, but indirectly each visitor has some impact," Liu said. "They come; they take their summer vacations there and stimulate the local economy, which in turn uses more local natural resources. We don't see ourselves as a destructive force, but we are."

They also more closely examined human population dynamics for further clues into why the rate of habitat destruction increased dramatically inside the reserve after the reserve was established.

"One thing ignored in traditional research is the importance changing population structure would have on biodiversity," Liu said. "Over time, the percentage of young people living in Wolong has increased. That means they have more labor force, more young people to go to the mountains to cut down the trees.

"People perceive protected areas as the last resource for protecting biodiversity. What they don't realize is that even high-profile protected areas like Wolong Nature Reserve may not be really protected."

Both Liu and Linderman point to the need for integrating ecology with human demography and behavior as well as socioeconomics to understand the role of protected areas in fostering biodiversity around the globe.

The National Science Foundation, NASA and the National Institutes of Health are the major funding sources that supported this research. This Landsat 7 project is part of NASA's Earth Science Enterprise, an interdisciplinary research program dedicated to improving our understanding of the Earth system and how it is changing due to both natural and human-induced processes.

Print

Print Email

Email