Spotted Lanternfly Biology

August 26, 2022 - Deborah McCullough

Spotted lanternfly (SLF) (Lycorma delicatula) is a native of China and other regions of Asia. Spotted lanternfly and other lanternflies are planthoppers in the family Fulgoridae, which includes approximately 140 genera and 716 species. Fewer than 20 species are native to the U.S. Most lanternflies are large insects that feed on trees in tropical regions of the world. Adult lanternflies are often amazing, with bright colors and a crazy long snout. Apparently, there are old folk tales that mention lanternflies with long snouts that glow in the dark – hence the “lantern” in the name lanternfly. In reality, the snouts don’t actually glow but species with names like “peanut bug,” “angry bride,” and “unicorns of the insect world” are worth checking out online!

Life cycle

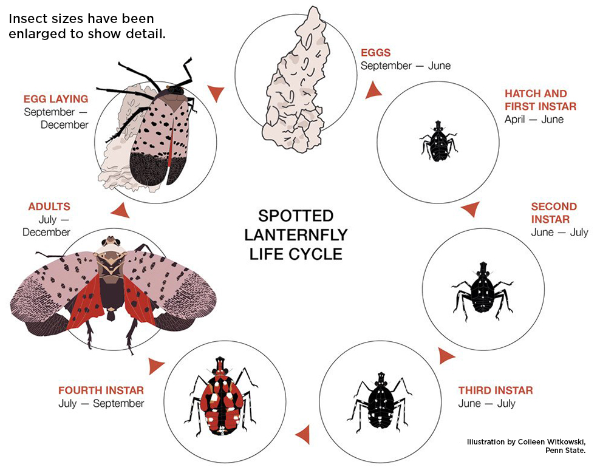

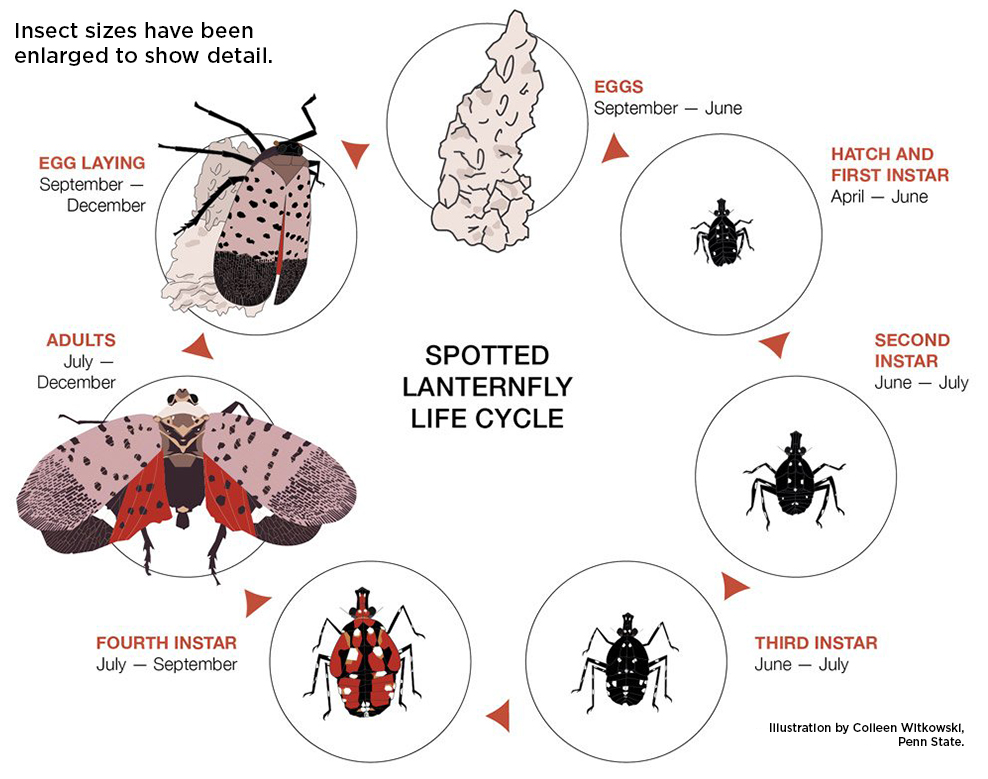

Spotted lanternfly has one generation per year via incomplete metamorphosis with four immature development stages or “instars” before becoming adults. Immature stages are called nymphs. First, second and third instar nymphs are black with white markings. Fourth instar nymphs, however, have striking reddish-orange bodies with black and white markings.

Adults, the only stage with wings, begin to appear in late summer and are active through early fall. An adult SLF is about an inch long and half an inch wide. The grayish forewings have black spots and markings. When the wings are extended, the red, white and black hindwings can be seen. A few adults may appear in mid-summer, but they are most common in late summer and fall.

Spotted lanternfly overwinters in the egg stage. Egg masses, each containing 30-50 eggs, are laid on tree trunks or branches but also on other types of hard or solid objects such as bricks, vehicles and landscape boulders. New egg masses appear to be coated with a shiny grayish substance that initially resembles fresh concrete. As the egg masses age, they crack and fade to a tan or grayish brown over time. Egg masses can resemble a small patch of mud or “seed pods” and can be found on vehicles, tree trunks, boulders and stones, bricks and other outdoor surfaces. Egg masses are present from fall until they hatch the following spring.

Hosts and Impacts

Like all planthoppers, spotted lanternfly are sap feeders. Their mouthparts include long stylets that can pierce the bark of tree trunks, branches or shoots or the woody portions of vines. In contrast to many other sap feeding insects, spotted lanternfly do not actually “suck” sap out of the plants. Because sap in the tissue of live plants is under pressure, when spotted lanternfly stylets pierce the tissue, the sap actually flows into the mouthparts of the insects. Thus, spotted lanternfly cannot feed on dead trees or on cut branches or shoots.

Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is by far the favorite host of spotted lanternfly. This tree, another native of China, was imported into Pennsylvania in the late 1700s and is now established across much of the U.S. It grows well on disturbed sites and poor soils and can often be found along highways and railroad tracks.

In addition to tree of heaven, spotted lanternfly can feed on approximately 70 other species of trees and vines, including stone fruit trees, grapevines and hops bines. Insecticides may be needed to protect these plants in areas where spotted lanternfly density is high. Many hardwood trees can also be fed upon by spotted lanternfly, including black walnut, maples, willow and poplars.

Fortunately, spotted lanternfly is NOT a pest that is likely to kill host trees. It does not vector any plant diseases. Flagging—i.e., few dead shoots—has been observed on walnut or soft maples in Pennsylvania where high densities of spotted lanternfly were feeding but injury to host trees has been minimal. Overall, the impact of spotted lanternfly on host trees is mainly caused by the prodigious amount of honeydew the insects excrete as they feed.

Plant sap is mostly water and sugars (carbohydrates), which means that sap feeding insects must consume and process lots of sap to get the nutrients they need to grow, develop and reproduce. They need to do something with all that extra sugar water, called honeydew. In the case of spotted lanternfly, the insects excrete it—and they excrete a lot of it! Honeydew will literally rain down from heavily infested trees, coating plants, driveways and outdoor items beneath the trees. Black sooty mold then grows on the honeydew, which can reduce growth and vigor of shrubs or herbaceous plants. Wasps and ants will often be attracted to the honeydew. It is not pleasant to reside in an area where spotted lanternfly densities are high, especially if thousands of spotted lanternfly adults are feeding, squirting out honeydew (check out the online videos!) and generally making a mess. Fortunately, this doesn’t last for more than a few weeks.

Insecticides can be used to reduce spotted lanternfly densities and protect trees or vines. Although spotted lanternfly are really good at jumping (hence the “hopper” in the name planthopper), swatting the insects with a flip-flop might help relieve some stress!

How does spotted lanternfly spread?

Adult spotted lanternfly are not great fliers, but they can disperse short distances into new areas. Artificial dispersal by people accidentally moving egg masses or other life stages is more problematic. Several infestations in other states have resulted from spotted lanternfly hitchhiking on vehicles, including cars, semi-trucks and trains. Once established, we expect spotted lanternfly populations will increase over time, eventually reaching the high densities that people have seen in Pennsylvania and other eastern states.

If you suspect you have come across spotted lanternfly egg masses, nymphs or adults in Michigan, note your location, either an address or GPS coordinates. Try to capture an insect or two and put them into a Ziplock bag or small jar. At the very least, take a picture while noting your exact location. Report suspected spotted lanternfly to Eyes in the Field, the website regulatory officials will monitor.

Report suspected spotted lanternfly sightings

Residents or visitors can also help prevent spotted lanternfly spread by checking vehicles and outdoor items like coolers or firewood for egg masses or other life stages before leaving any area where spotted lanternfly is established.

If tree of heaven grows near your residence, check the trees for spotted lanternfly egg masses or other life stages. Also, consider reporting the location of the tree of heaven into the Midwest Invasive Species Information Network (MISIN). These locations may be valuable in the future for guiding survey protocols and priorities.

To learn more about spotted lanternfly, check out this Michigan State University Extension bulletin, “Spotted lanternfly: A colorful cause for concern.”

Print

Print Email

Email