David Ricardo came from a London stockbroking family, made most of his considerable fortune from speculation during the financially turbulent Napoleonic war era, cashed in and retired to an English country estate. In his leisure he made two important contributions to our understanding of agricultural markets. One was to develop the law of comparative advantage that underpins the view that international trade is generally beneficial to both trading countries. Although a landowner, he advocated for the repeal of Britain’s grain tariff laws and his logic on the benefits of trade was influential in eventually opening up European markets to North American grain. The other contribution, that of cash rent determination, is the matter of this article.

David Ricardo came from a London stockbroking family, made most of his considerable fortune from speculation during the financially turbulent Napoleonic war era, cashed in and retired to an English country estate. In his leisure he made two important contributions to our understanding of agricultural markets. One was to develop the law of comparative advantage that underpins the view that international trade is generally beneficial to both trading countries. Although a landowner, he advocated for the repeal of Britain’s grain tariff laws and his logic on the benefits of trade was influential in eventually opening up European markets to North American grain. The other contribution, that of cash rent determination, is the matter of this article.

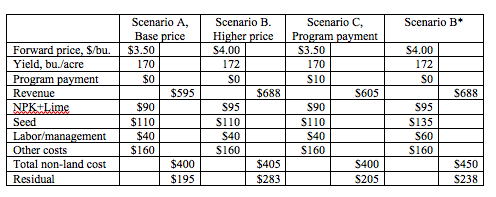

Ricardo’s view of cash rent in agriculture is based on the assumption that land is essential for crop production. More than that, it holds that land is the single most important factor in production. To understand the importance attached to land rents, consider an example corn land budget under alternative revenue assumptions as laid out in Table 1. The table is intended as illustration, so please forgive the economist’s tendency to disregard such details as crop insurance, how rotation needs affect rent, etc. Labor costs have been inserted to account for returns to both management and operation effort.

With expected yield at 170 bushels per acre, a spring-time locked in forward price at $3.50/bushel and an assumption of no program payments then Scenario A involves expected revenue at $595/acre and costs at $400 leaving the residual, or surplus, at $195/acre. As all costs have been paid for except that of acquiring access to the land, then this amount could be paid out in order to break even. It is the amount that the owner-operator can ascribe to returns on owning the land and it is the amount that the renting operator might pay as cash rent.

Table 1. Example corn land crop budget and residuals for land under alternative revenue assumptions, all values are per acre

Scenario B continues to hold program payments at zero but has a higher forward price, namely $4.00/bushel. We assume that the operator, whether owner or not, will increase fertilizer inputs in response and so expect 172 bushels/acre. The residual then becomes $283/acre. Ricardo’s view was that rent should increase by this difference, or $288-$195=$93/acre. Most of this comes from the price increase but some also comes from adjustments to production. Of course, the above logic should also work in reverse. Were the corn price to decline to $3.00/bu. then cash rents would decline by an amount just short of 0.5x170=$85 when one allows for a bit of a pull-back in inputs and yield.

Scenario C returns to the price and yield assumptions in Scenario A but introduces a $10/acre program payment that is not tied to production, as in the direct payments that were in place between the 1996 and 2014 farm bills. As the $10 is received regardless of production choices, all costs are held fixed and yield remains at 170 bu./acre. The $10 passes through entirely to the residual, which increases from the Scenario A value of $195/acre to become $205/acre. We defer consideration of Scenario B* until we make some comments about how scenarios B and C compare with A.

As with most theories, including Newton’s theory of gravity, Ricardo’s theory of cash rent can be picked apart upon closer inspection. What is it about land that, in Ricardo’s view, allows the owner to be the residual claimant on the profit effects of good and bad shocks? His view was that land is the ultimate scarce resource for crop production and that provides the owner with strong bargaining power. The other factors in production, including nutrients, seed and labor/management, can be readily replicated or pulled from other sectors so their prices won’t shift as a result of a change in crop sector profitability. But is this extreme stance on the special nature of land really tenable?

It is likely largely true for some inputs. For example, nitrogen is abundant in the atmosphere. The cost of fixing it depends largely in the price of natural gas and is unlikely to vary too much with crop prices or government payments. However, for other inputs there are stronger grounds for debate. The few seed companies do compete but that competition is far from perfect because there are so few, because they also own important scarce resources in the form of patents and elite genetics, and because firms with specific hybrids/varieties well-adapted to a region may dominate the local market. More so than, say, 50 years ago, seed companies can bargain for some of any additional surplus in the sector.

Bargaining power is also likely present in the tenant labor/management input. Modern crop production is a technologically and cognitively challenging business where prospective tenants will differ greatly in how they are positioned to extract profit from the land. Better management is also a scarce resource and can bargain for some of any additional surplus. In addition, location of tenant home base and transportation costs matter when seeking to make best use of expensive cropping equipment. In reality the landlord has available only a limit the number of prospective tenants to bargain with. With crop land in less crop-intensive areas, say on the periphery of the corn belt, tenants may have more bargaining power when compared with central corn belt land.

The small number of landlord-tenant matches also means that cash rent responses are likely to be sluggish. Formal fixed-rate cash rent contracts may extend to multiple years. In addition, when commodity prices move to a persistently higher range then landlords may be reluctant to press a good tenant for an upward adjustment while when prices fall then tenants may worry that efforts to bargain down the rent will lead to a loss of very accessible crop land.

Scenario B* adjusts Scenario B to allow for some bargaining power on the part of seed companies and prospective tenants. In B* the effect of a $0.50/bu. corn price increase relative to Scenario A still creates the same surplus but only half of it ultimately passes through to the landlord. This 50% pass-through is around about what academic research on the matter finds.

Ricardo’s rent theory has found applications elsewhere in agriculture: for example in understanding water rights and the right to produce or market quotas for milk, tobacco or peanuts. Before Uber upended the medallion system in big city taxi markets, the approach was a very useful way to understanding medallion pricing. Seats on trading exchanges can also be viewed this way. In each case, however, closer inspection will reveal that the market is a little more complicated so that less than 100% of profit shocks will pass through to the owner of the right. So what do you think? Maybe two thumbs up to Ricardo for a thought-provoking way to think about the matter and one thumb up for the truth of his claim?

Acknowledgements: This research was funded by the Elton R. Smith Endowment in Agricultural and Food Policy.

Originally published in Michigan Farm Bureau's Michigan Farm News

Print

Print Email

Email