Planned unit development provides flexibility in local zoning

Zoning ordinances are often not very flexible, requiring neighborhoods or commercial areas to appear the same. Planned unit development is one tool which can provide more flexibility and innovation for development.

One of the critiques of zoning is that it is not flexible, and results in “cookie cutter” neighborhoods of sameness. Sort of like the target of the 1960s protest song Little Boxes sung by Pete Seeger in 1963:

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky tacky,

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes all the same.

There's a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one,

And they're all made out of ticky tacky

And they all look just the same.

(Little Boxes words and music by Malvina Reynolds; copyright 1962 Schroder Music Company, renewed 1990).

In 1980, Michigan amended its zoning enabling acts to allow for more flexibility in zoning. Today, the Michigan Zoning Enabling Act (MZEA), houses that authorization at MCL 125.3503.

That added flexibility is called planned unit development (PUD), which allows for mixed-land uses in a single development, and clustering and flexibility in design of a PUD’s parcels. Others may refer to this practice by other names: cluster zoning, planned development, community unit plan, planned residential development and other terminology.

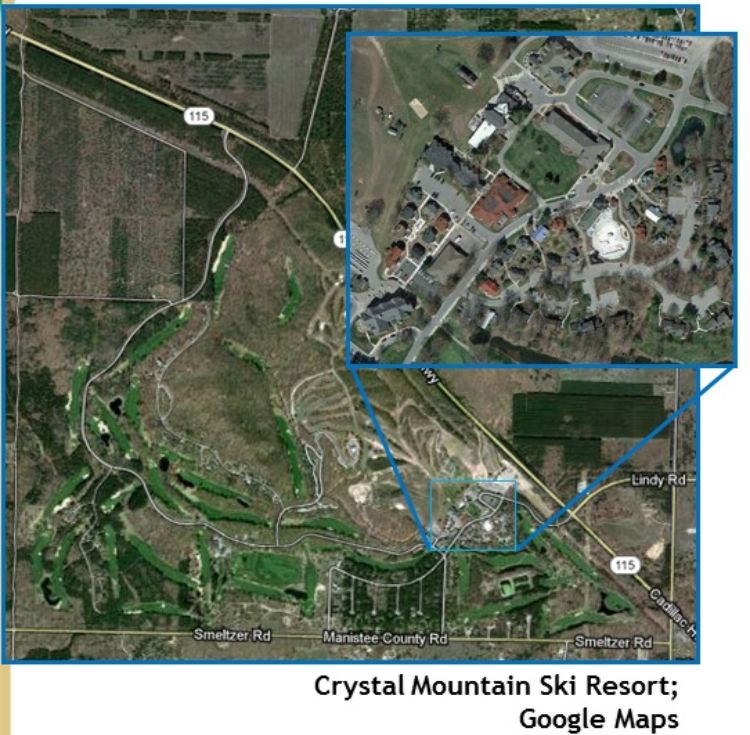

An example of this could be a ski resort. A typical northern Michigan ski resort will take advantage of a PUD’s ability to mix different land uses into one development. Think about the mix of uses and clustering that is in a typical ski resort:

- Ski hill (open space)

- Golf course (open space)

- Hotel/motel

- Restaurant

- Health club

- Pro shop

- Ski shop

- Other retail and services

- Conference center

- Trails (open space)

- Single family and multi-family housing

All of this may be owned by one person; all one parcel, all very flexible in design.

The second aspect of a PUD is flexibility with the parcel sizes and shapes. For example, zoning might require a 15,000 square foot minimum parcel size, or a parcel that is 100 feet by 150 feet in size. That means two to three parcels per acre. So if one has 10 acres, they may be able to create 25 parcels (after land for streets is taken out). But a PUD can allow clustering, so the 25 parcels occupy only five of the 10 acres because there is a desire to keep open space (wetland, scenic view, recreation area) on the other five acres. The PUD allows each parcel to be about 7,500 square feet, instead of 15,000 square feet. But the overall density of 25 for the entire 10 acres is the same in this example.

In this PUD example, the development starts out as one parcel and owner, but when done several different land owners, and 25 different parcels are created.

A PUD can also be set up to allow both the clustering and mix of land uses in one project. A PUD can be done in conjunction with various different means of splitting and conveying land. It can be done in coordination with creating a subdivision, creation of a condominium of the surface of land, leasing property and land divisions.

A criticism of PUD is that the process to obtain approval can be involved and time consuming. So developers may be encouraged not to seek a PUD approval. The MZEA provides local governments with two options for the review and approval of a PUD. The local zoning ordinance has to specify which one of the two options is used in the zoning jurisdiction.

The first option is to handle the PUD like a zoning amendment. When done this way, it is a legislative, or policy decision, and the legislative body makes the final approval (township board, village council, city council, county board of commissioners). The zoning ordinance must also specify:

- Conditions for eligibility

- Participants in review process

- Requirements, standards for review

- Procedures for application, review

- Planning commission recommends, legislative body adopts amendment

The second option is to handle the PUD like a special use permit. When done this way, it is an administrative decision. Most often (and recommended) the final decision is made by the planning commission or zoning staff. The zoning ordinance must specify:

- Conditions for eligibility

- Participants in review process

- Requirements & standards for review & approval

- Procedures for application, review & approval.

- Who approves the PUD (which can be the planning commission (usually), administrative official (zoning administrator) (sometimes), or legislative body (more rarely) (not recommended).

A comparison between PUD as an administrative versus as a zoning amendment shows: When done administratively, the review time is faster, and the decision is based on standards spelled out in detail in the zoning ordinance. The reviewing body must produce a findings of fact and detail its reasons for the decisions. If all the standards ae met, then the PUD must be approved. If handled as a zoning amendment, the review time takes longer (a disincentive to use the PUD), but there is more flexibility and more discretion to say “yes” or “no” to a PUD request.

Michigan State University Extension educators specializing in land use, can assist further with PUD, or one can participate in the Michigan Citizen Planner program where this and many zoning concepts are introduced.

Print

Print Email

Email