Anybody can teach science: Test of strength

Teach science with a couple milk jugs—it’s that easy!

You don’t need all the answers to teach science—you simply need an inquisitive mind and be willing to carry out an investigation. You can teach science, even when you don’t know diddly-squat! The following is a simple experiment you can try with just a couple of milk jugs. The purpose is not to teach specific content, but to teach the process of science: asking questions and discovering answers. This activity is to encourage young people to try to figure things out for themselves rather than just read an answer on the internet or in a book.

Test of strength experiment

This activity can be done in 20 minutes or multiple days, depending on the interest and questions the youth have. Materials needed include two milk jugs full of water (or more if you want) and a stopwatch (or stopwatch app for a phone).

Use Science and Engineering Practices to engage youth in the experiment. These are connected to in-school science standards that all children must meet.

- Asking questions and defining problems

- Developing and using models

- Planning and carrying out investigation

- Analyzing and interpreting data

- Using mathematics and computational thinking

- Constructing explanations and designing solutions

- Engaging in argument from evidence

- Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information

Asking questions and defining problems

Who do you think is the strongest in your group? How could you measure strength? Do you think there are things you could do in the short term to make you stronger? Do positive or negative words make a difference?

Planning and carrying out investigations

Have a youth hold a jug filled with water in each hand and hold them straight out from their body. Everyone else should be completely quiet. Time the student to see how long they can hold the jugs without dropping their arms.

Give the person some time to rest (or let someone else try the experiment) then run the experiment again with the rest of the group giving positive reinforcement to the person. “Great job!” “You can do it!” “You are so strong!”

After another period of rest, repeat the experiment with negative comments. “You are a wimp!” “You will never be able to do it!” “You stink!” Make sure you record the time in each trial.

Analyzing and interpreting data

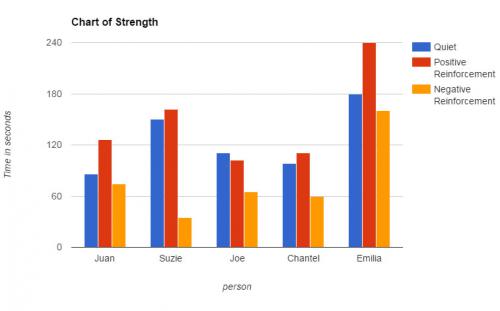

Graph the results. Use different colors for quiet, positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement. See below for an example:

Using mathematics and computational thinking

Which trial produced the longest result? Which produced the shortest? Why? Did everyone do better with the positive reinforcement? Why or why not? If you were given a person’s “quiet” results, could you predict how well they would do with positive reinforcement? How about negative reinforcement?

Engaging in argument from evidence

Why do you think sports teams have bands and cheerleaders? If you were designing a sports arena, would the information you gathered in this experiment affect your design? Have a discussion about what made the biggest difference in the amount of time. Why? Could the information gained in this experiment apply to other things, such as performance in schools or on tests? Productivity at work?

Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information

Pretend you are a principal at a school. Have the youth you are working with try to convince you to spend time or dollars from a school budget on positive reinforcement activities.

Related questions to explore:

- Does what people say about themselves affect their strength? How could you test that? Could what someone says about themselves counteract what others say about them?

- Does competition affect how well people perform? Is there a way you could test that with this experiment?

Print

Print Email

Email