Clay soil moisture monitoring project explores farmer’s efforts to improve drainage

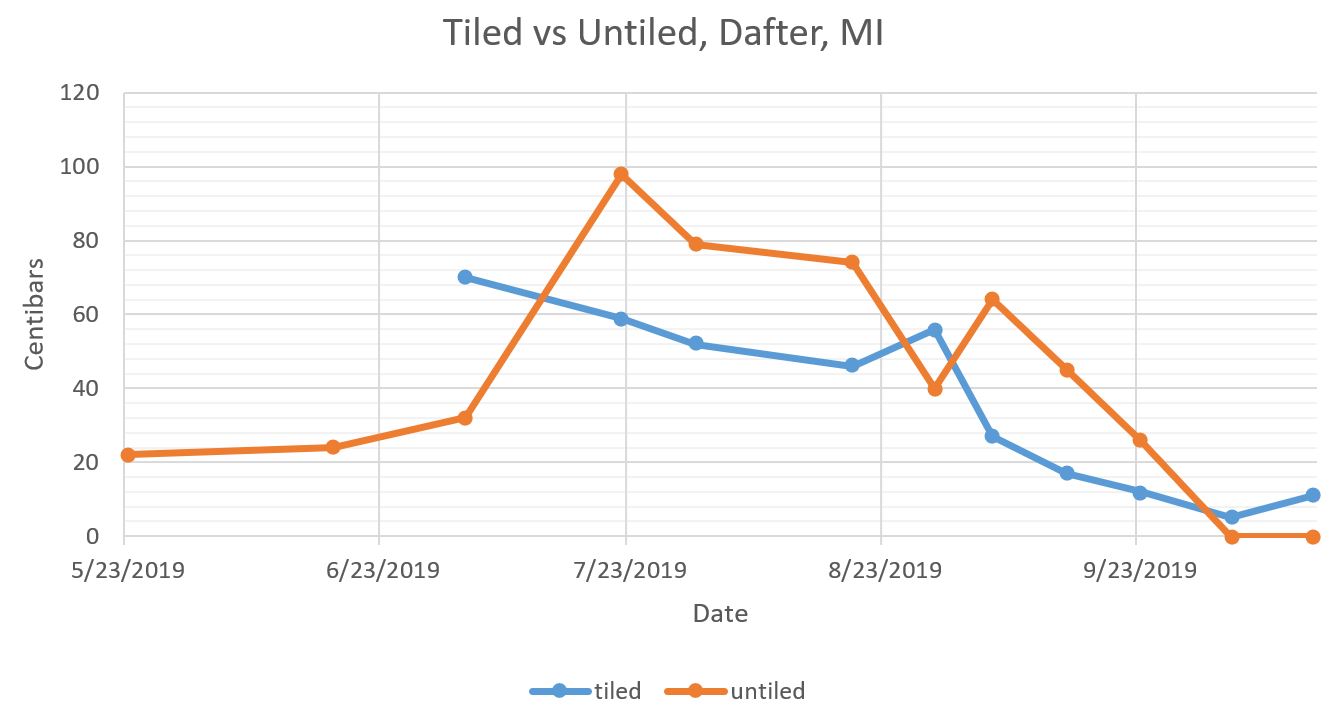

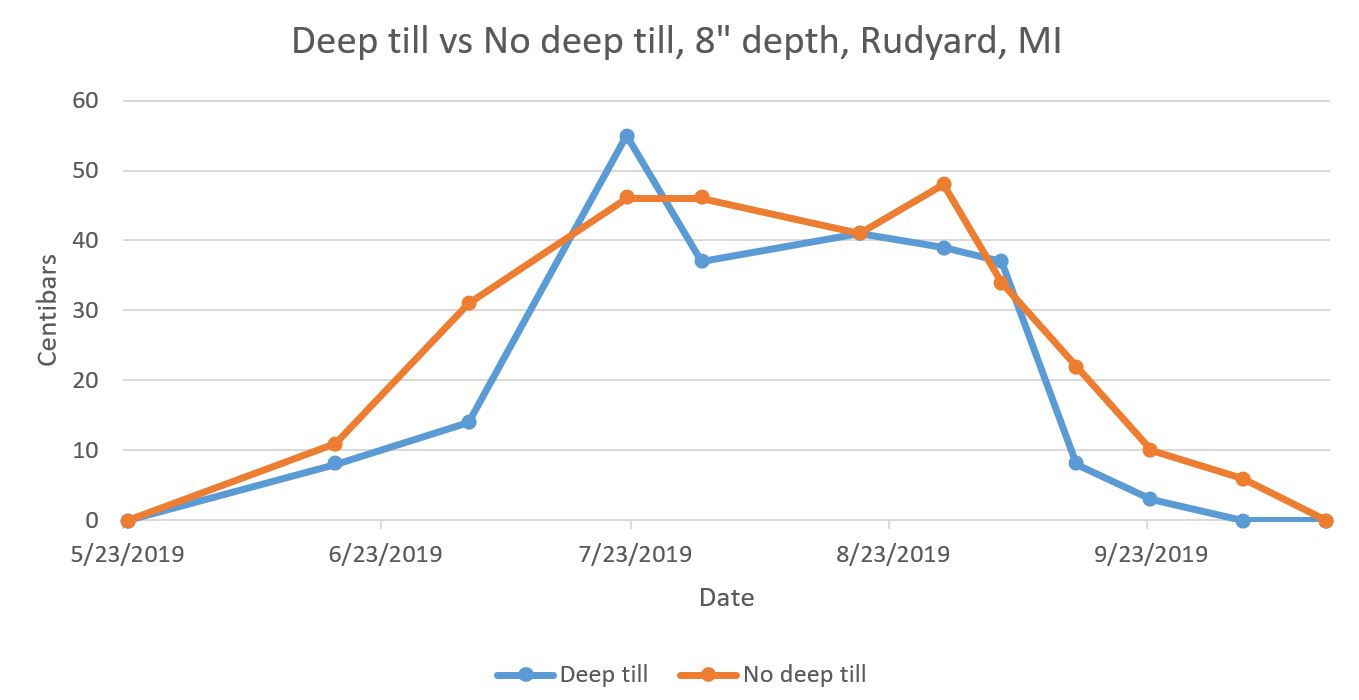

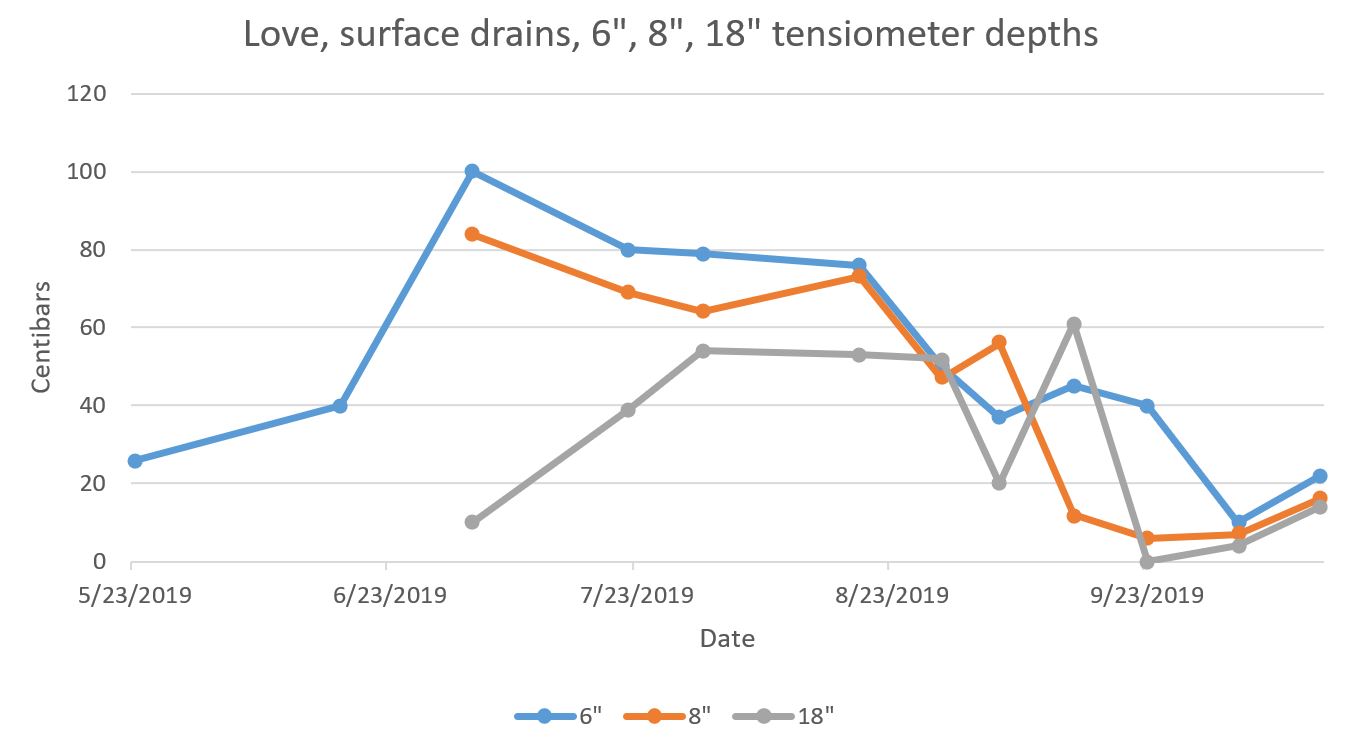

This season-long demonstration project compared results of surface drains, deep tillage and field tile on Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula farms.

There are two extensive areas of clay soil farmland in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula located mostly in Chippewa-Mackinac County area and the Baraga-Ontonagon-Houghton County area. These soils currently support large acreages of perennial hay production supplying beef cow-calf farms, a few dairy farms and significant hay export activity. Poor soil drainage, naturally low fertility and acidic pH, along with a short growing season, limit the productivity of these soils.

Needs assessment round-table meetings with farmers in both areas were held in 2014 and 2018. Improving field drainage emerged as a highly important issue in both groups, along with soil biology and fertility, hayfield rejuvenation, grazing season extension and managing trefoil and other forage species, all strongly related to soil drainage.

Improving soil drainage has potential for significant impact on local agriculture based on ability to graze or plant earlier in the spring and graze or harvest later into the fall. Possibilities also include a wider selection of potential crop choices and expanding from the current one-cut hay system to a two-cut system. Traditionally, farms in the eastern Upper Peninsula use surface drains to move excess water off flat fields. Some Upper Peninsula farmers have adopted practices to improve drainage on their clay soil fields, including subsurface (tile) drainage installation, deep tillage at hayfield establishment and using vertical tillage on live sod, such as using the Aerway soil aeration implement.

To explore differences in soil moisture status between farms using these methods, Michigan State University Extension educator Frank Wardynski and I developed a demonstration project to monitor soil moisture on fields where drainage efforts are in place versus nearby fields without the effort. Soil tensiometers were installed on three farms in Chippewa County and three farms in the Ontonagon/Baraga area. Some tensiometers were backordered and installed after the project began.

Drought conditions in the western Upper Peninsula prevented collection of meaningful soil moisture data. However, readings were completed on the eastern Upper Peninsula farms. Participating farms were visited roughly every two weeks. Tensiometers were removed Oct. 11 to prevent damage from freezing temperatures. The tensiometer gauge indicates centibars, a measure of vacuum created by the soil drawing moisture through the buried ceramic tip of the water-filled tool.

It is important to note with these types of sensors that a lower number indicates a wetter soil. Irrometer readings from 0-20 indicate a very wet soil. Interpretation of centibar readings based on percent of soil water depletion on a variety of soil types can be found in “Irrigation Trigger Levels – Soil Types” from Nebraska State University.

Demonstration summary

- Ideally, the tensiometer gauges would be read daily or every few days. Time and budget constraints allowed for much less frequent readings. However, the numbers as recorded provide a series of snapshots to compare soil moisture conditions where the techniques (deep tillage at hayfield replanting, drain tile, surface drainage) are in use.

- During dry periods in the eastern Upper Peninsula, the tensiometers needed recharging with fresh water before readings could be taken. In some cases, this maintenance resulted in questionable readings. Severe drought in the western Upper Peninsula made readings irrelevant since no differences were apparent and the need for constant maintenance made the tensiometer tool undependable.

- This soil moisture monitoring demonstration documented soil moisture conditions over a single season and provides insight into practices currently in place on eastern Upper Peninsula farms.

- See “Agricultural Drainage,” MSU Extension Bulletin E3370 by Ehsan Ghane, for more information.

For more information, contact Jim Isleib at isleibj@msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email