Good urban form promotes walkability and physical health – Part 2

The physical layout and design of a city directly determines how accessible, welcoming, convenient, and safe the city is for walking, all of which are important for enabling and encouraging more physical activity among residents.

The first of this two-part series on urban form and walkability introduced the notion that urban form affects walkability in four basic ways, as explained by the Walkable and Livable Communities Institute:

- How accessible the environment is to pedestrians

- How welcoming the pedestrian environment is to walkers

- How convenient the area is for walking

- How safe the pedestrian environment is to walkers

The first two factors were explored in part one of this series and the second part of the series describes how urban form affects the convenience of the city for walking and the safety of the pedestrian environment.

Urban form that is convenient to pedestrians consists of many connections in the transportation network that result in shorter distances between where people live and where people want to go. Smaller city blocks (200 to 400 feet in length) and features like alleys that offer mid-block access provide direct routes for pedestrians and promote walking. Also, the incorporation of other modes of transportation in the street network, such as bicycling and public transportation, make getting around town much more convenient for non-motorized travelers (see the Michigan State University Extension News article “What is a ‘complete street’ and why is it important?”

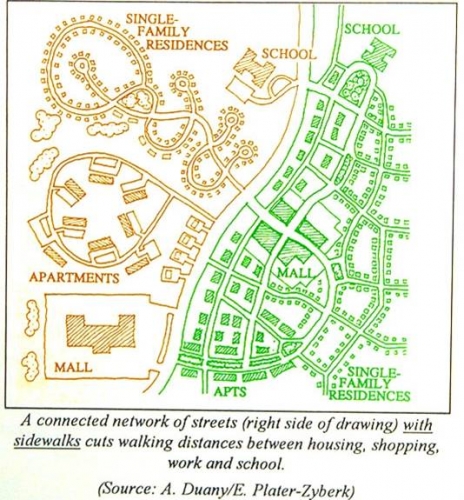

At the community-wide scale, convenience from a pedestrian standpoint, equates to mixed-use patterns of development in which residences are built close to (and part of) existing retail shops, restaurants, and community services (schools, library, post office). This urban form is in stark contrast to one with segregated land uses in which residential areas are isolated from other uses and walkability is discouraged (see Photo 1). A mixed use pattern of development within a neighborhood setting means more trips for basic goods and services can be made on foot and bike.

Photo 1:

The separation of uses (on the left) encourages driving, whereas the mixed use patterns of development (on the right) encourages walking.

The fourth aspect of urban form that affects walkability is the safety of the walking environment, which either discourages or encourages pedestrian use. Safety is strongly linked to people’s perceptions, and while crime may not be an actual problem, the fear of crime can result from poorly designed and poorly maintained urban areas, which discourage walking. Keeping the pedestrian environment well-lit and free of litter and debris improves both the reality and perception of safety. Urban form can also keep the pedestrian environment safe by placing ‘eyes on the street’. When buildings are oriented to the street and have front porches and/or numerous windows that allow for interaction between those inside and those outside, pedestrians feel safer and crime is deterred (see Photo 2). Also, safety is dependent on the number of users on the sidewalk and regular use adds to the number of effective eyes on the street.

Photo 2:

We feel safer both inside and outside when there is a high degree of transparency in the building façade (Photo credit: Kurt Schindler).

In conclusion, there is much more to walkability than simply providing sidewalks. The physical layout and design of buildings, streets, and sidewalks and the siting of open space, public facilities, and other uses directly determine the walkability of our communities. When combined in the right urban form, components of the built environment contribute to walkability and promote physical health.

Print

Print Email

Email