Great Lakes also experience seasonal temperature changes

Exploring the seasonal transition within the Great Lakes. Do you know your hypolimnion from your epilimnion?

As the seasons turn, so too do the Great Lakes. With the cold weather comes a process called “turnover.” During this seasonal transition, temperature and oxygen levels are affected — and contribute to how much life the Great Lakes can support.

These changes in temperature and oxygen level are explored in separate lessons available at the Teaching Great Lakes Science webpage, developed by Michigan Sea Grant in collaboration with Michigan State University Extension and other partners. These lessons are available at no cost to teachers, non-formal educators or those simply interested in learning more about the natural biological process of the Great Lakes.

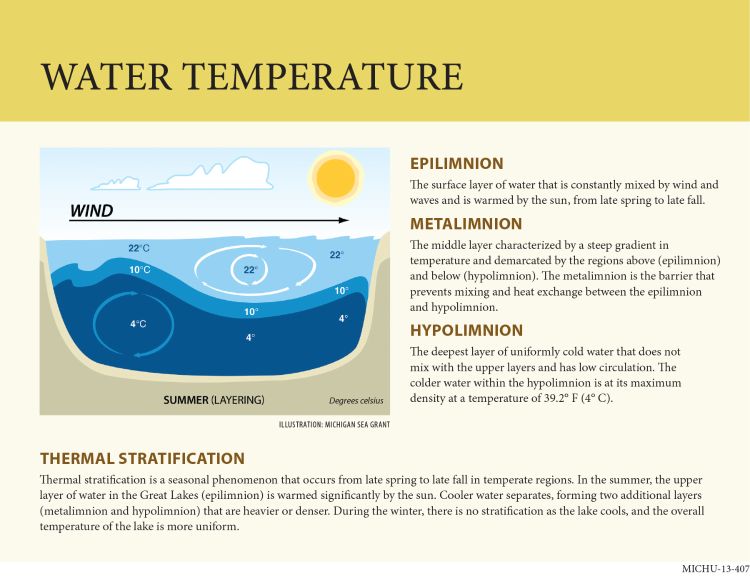

View full-size Water Temperature Infographic

Water in a lake separates into warm and cold “layers” during summer. When this happens, scientists refer to the lakes as being stratified. During the layering process, lakes undergo what is called thermal stratification.

How do they become layered? Stratification happens as a result of water’s temperature-dependent density. Warm water near a lake’s surface (the top layer) warms from the sun and can be several inches to many feet deep depending on the size of the lake and the amount of sun it receives. As water temperature increases, the density decreases, and therefore the warm water remains at the surface. A lake’s surface layer of warm water is called the epilimnion.

Cooler water, which is denser than warm water, sinks to the bottom. The cold, deep waters form the hypolimnion (the bottom layer). During summer, these cold, bottom waters do not mix with the warm surface water. At the beginning of the summer, the hypolimnion will contain more dissolved oxygen because colder water holds more oxygen than warmer water. However, as time passes, the hypolimnion will contain less oxygen and nutrients than the warmer waters above because of decomposition of organic matter and respiration by animals and plants living there. Deep water fish, such as salmon and lake trout, generally swim in the cold waters of the hypolimnion.

A thin layer of water called the metalimnion — or thermocline — separates these warm and cold layers of water.

In the fall, Great Lakes surface waters begin to cool. When the water temperature drops near 4 C or 39.2 F, it reaches maximum density or heaviness, and it sinks. When that happens, the top water descends to the bottom of the lake, which causes a lake’s waters to mix. Wind also plays a role in this mixing. Since wind is typically stronger during fall, it helps mix the whole water column from top to bottom.

This seasonal mixing — called turnover — also occurs in the spring. Seasonal mixing is important because it introduces oxygen to different layers within the lakes and also helps circulate nutrients through the water column.

More Information

For more information and related lessons from Teaching Great Lakes Science, see:

- Properties of Water – Water density and seasonal cycles

- Oxygen in Water – Dissolved oxygen, life and dead zones

Print

Print Email

Email