Local governments weigh in on Grand River Waterway dredging project that would destroy fish habitat

State funding was appropriated for channelization of 22.5 miles of the Grand River. Downstream communities are voicing concerns over long-term economic and environmental costs.

The Grand River Waterway is a proposed seven-foot deep, 22.5-mile long channel that would involve dredging portions of the Grand River between Fulton Street in Grand Rapids and Bass River State Recreation Area in Eastmanville. The channel would allow large powerboats to travel from Grand Rapids to Grand Haven and would remove 50 acres of shallow-water fish habitat. Removal of these shallow areas would likely have additional impacts that would ripple through the river environment for decades to come.

At first glance, the notion of improved access for boaters looks like a great idea for improving tourism and benefiting the local economy. However, the hidden environmental and economic costs of de-stabilizing a river channel must be carefully considered. Michigan State University Extension and Michigan Sea Grant have published a white paper on the potential physical and biological impacts of this project, and the Grand River Waterway organization has a feasibility study detailing the extent and cost of dredging available on its website.

Channelization vs. harbor dredging

Many west Michigan communities are aware of the economic benefits of harbor dredging, as well as the difficulty in securing federal or state funding to maintain navigable harbors. Harbors are typically located in river mouth areas and associated lakes, where dredging is used to maintain a deep channel connection to Lake Michigan.

The Grand River Waterway project proposes to dredge a free-flowing river environment that is very different from the “freshwater estuaries” found at Great Lakes river mouths. This project would seek to allow boats up to 49 feet long to cruise upstream 40 miles from Lake Michigan by digging out the bottom of the river and removing snags and other obstructions. This type of river modification is known as channelization and is recognized by Michigan Department of Natural Resource’s (MDNR) Wildlife Action Plan and Grand River Assessment as one of the most serious threats to big river ecosystems and the unique species that reside there.

History of Grand River channelization projects

This is not the first time that channelization has been proposed to improve navigation between Grand Rapids and Lake Michigan (see 1978 study). The section of the Grand River between Grand Rapids and Eastmanville was naturally shallow, and the first dredging project was a four-foot deep channel that was approved by the River and Harbor Act of 1881. This initial attempt was never completed, and an 1887 report concluded that highly variable water levels and ongoing problems with deposition of sand and silt made construction of a permanent channel within the riverbanks impossible.

A more elaborate engineering project was authorized in 1896 and modified in 1903 to provide a six-foot deep channel. In order to prevent the shifting sand of the river bottom from filling in the channel immediately, training walls were constructed of pilings and “mattresses” of woven pile and brush.

These walls were constructed parallel to the river banks within the river channel. Sediment was dug out from what would become the navigation channel, and this sand and silt was deposited between the training wall and shore. This effort artificially deepened and narrowed the river channel through dredging and the construction of 25 miles of training walls within the river channel. Despite the scope of this undertaking, the channel was officially abandoned by the federal government with passage of the River and Harbor Act of 1930.

Most of the training walls remain in the Grand River, buried beneath over a century’s worth of accumulated sediment. In places, the river has broken through the walls and cut a new channel. In other places, new land has formed as the river adapted to the modifications of its bed. The walls still hold back vast quantities of sediment pulled from the middle of the river circa 1910.

Erosion and related impacts to the river

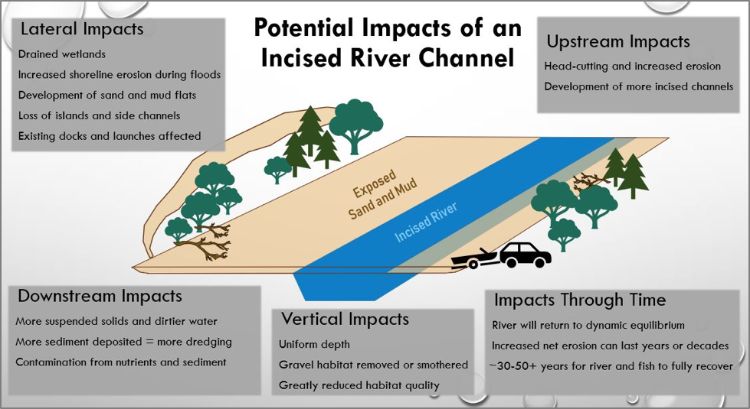

Channelization projects typically lead to increased net erosion. Dredging cuts into the bottom of the river, making it deeper and faster in the dredged portion of the river. The deeper, faster water erodes more sand and other sediment, which is then deposited downstream or on floodplains following high water. The exact location and severity of effects are difficult to predict, but many studies from around the world have documented harmful, and sometimes disastrous, consequences (see white paper for full documentation).

- Along the Blackwater River, Missouri, channelization caused excessive bank erosion and damaged bridges. Sediment deposition on shore was so deep that it buried fences.

- In the Missouri River, Kansas, channelization led to the loss of side-channels and islands when eroded sediment was deposited in side-channel areas.

- In western Tennessee, several rivers experienced so much erosion after channelization of upstream areas that channel blockages formed where sand and silt settled out in downstream areas. These blockages prevent navigation in downstream areas and lead to stagnation of river water.

- Dredging typically harms water quality by increasing turbidity and suspended solids. Peak sediment loads increased by a factor of 7 after channelization of the River Main, Northern Ireland.

- Channelization can lead to development of an incised river, which can lower the water table and drain adjacent wetlands (see image and videos).

- Wakes from large boats lead to further erosion and muddy water. One study from the Waikato River, New Zealand, found that boat wakes were 100 times more powerful than natural river waves and carried up to 23 times as much soil away from the riverbank.

Harm to fish and other aquatic life

In addition to the direct destruction of 50 acres of shallow habitat, dredging to channelize the Grand River would likely reduce populations of gamefish and other sensitive fish species by harming water quality, reducing water clarity, reducing the number of insects and other invertebrates that fish feed upon, and damaging additional spawning and nursery habitat.

- Channelization led to a 90% decline in fish food in the River Moy, Ireland.

- Channelized sections of the Chariton River, Missouri, have 80% lower total fish biomass relative to natural sections.

- A study of 40 Indiana streams found 50% fewer sensitive fish species in channelized vs. natural stream sections.

- Destruction and degradation of spawning and nursery habitat led to fewer trout and salmon relative to less valuable fish species on the River Boyne, Ireland.

- The average size of largemouth bass was 8 times higher in natural vs. channelized sections of the Luxapalila River in Mississippi and Alabama due to lack of habitat for large bass.

- Removal of snags and other woody debris for navigation eliminates fish-holding areas and fish food. Snags were found to hold 20-50 times more invertebrate biomass than sandy areas in the Satilla River, Georgia.

- Dozens of sensitive species are associated with the Grand River corridor in Ottawa County, including 18 freshwater mussels and 2 snails. Channelization is among the leading causes of extinction for freshwater mussels and snails in North America, and two state threatened mussels have been found in the proposed dredging area.

- The proposed path of the Grand River Waterway would dredge through shallow gravel habitat that provides quality fishing for a variety of gamefish in addition to providing spawning habitat for state threatened river redhorse.

Economic consequences

A study was commissioned by Grand River Waterway to demonstrate economic benefits of the channelization project and building of a 250-500 slip marina in the Grand Rapids area. That study did not address economic benefits that the natural, un-channelized Grand River currently provides, nor did it address the impact of dredging on current uses and economic impacts. The current un-channelized river corridor is used for activities including kayaking, canoeing, fishing, birdwatching, and hiking in numerous parks along the river that provide a peaceful environment for recreation. Existing businesses like the Grand Lady, a 105-foot long riverboat, and several fishing guides also regularly navigate the un-channelized river and could suffer from the impacts of dredging.

The Grand River Waterway Economic Benefits Study also stated that “improved water quality may generate up to 49,000 new visitor days annually” even though this type of river channelization project often leads to reduced water quality. The potential economic consequences of dirtier water, reduced fishing opportunities, erosion of private and public lands along the river, and deposition of sediment in downstream areas were beyond the scope of the economic benefits study.

Even so, these detrimental but unquantified effects have been recognized by communities along the lower Grand River. Some additional unaccounted costs including the need for additional marine patrols and annual maintenance costs for dredging, snag removal, and buoys were highlighted at a work session of the Ottawa County Board of Commissioners on April 9, 2019.

Opposition and support

The Ottawa County Board of Commissioners passed a resolution in opposition to the project on April 23, 2019, following the passage of similar resolutions by the Ottawa County Planning and Policy Committee and the Ottawa County Planning Commission. A separate resolution of opposition was passed by the Ottawa County Parks and Recreation Commission on April 2, 2019.

Additional resolutions in opposition to the Grand River Waterway have been passed by:

- Crockery Township

- Grand Haven City Council

- Grand Haven Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Grand Haven Chamber of Commerce

Local organizations with concern for the river have also raised concerns. The West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC) passed a resolution in opposition to the dredging and provides an overview of the issue on their website. The Grand Rapids Steelheaders and Grand Haven Steelheaders passed votes in opposition to the project, and the Friends of the Lower Grand River formed recently in response to the possibility of river dredging. The Friends group drafted talking points on the dredging issue and also provides several related documents on their website.

Georgetown Township’s Finance Committee passed a resolution in support of the Grand River Waterway in July 2018. The Grandville City Council voted to table a similar resolution in 2018.

Although opposition has been strong at the local level, $3.15 million in state funds were appropriated for this project with the most recent $2 million approved during the Legislature’s lame duck session in 2018. While $150,000 in state funds are to be directed toward sediment boring study, the remaining $3 million is specified for dredging and related activities on the Grand River once permits are acquired. Former state Sen. Arlan Meekhof has been very supportive of the Grand River Waterway project, as evidenced by his editorial and this rebuttal in the Grand Haven Tribune.

Current state legislators Rachel Hood (D-76th House District), David LaGrand (D-75th House District), and Winnie Brinks (D-29th Senate District) have been actively working against the dredging and recently sent this letter to Governor Gretchen Whitmer and MDNR Director Daniel Eichinger calling for a halt to all state funding related to the Grand River Waterway project.

The future of the project is now uncertain, and legal questions related to the rights of riparian landowners faced with the prospect of a state-funded dredging project have yet to be resolved.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 33 university-based programs.

This article was written by Michigan Sea Grant Extension Educator Dr. Dan O'Keefe under award NA14OAR4170070 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email