Michigan’s biochar

Chris Saffron and Mike Person of the Great Lakes Biochar Network discuss the properties of biochar and its industry potential in the Great Lakes region.

Biochar has grown in popularity as an agricultural product throughout the U.S. but has yet to become a major industry in the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region. The Great Lakes Biochar Network (GLBN) is working to change this by combining research, manufacturing partnerships and consumer education to share the potential uses and benefits of this ancient soil amendment. In the most recent episode of “In the Weeds,” a podcast from the Michigan State University Extension field crops team, Brook Wilke and Monica Jean sat down with Chris Saffron, an associate professor of biosystems and agricultural engineering at Michigan State University, and Mike Person, the program coordinator for the GLBN, to chat about “char!”

Biochar is created by heating biomass, such as jackpine wood, switchgrass or poultry litter, at high temperatures in chambers that have little to no oxygen. This process, known as pyrolysis, also produces gas from the reaction which can be used to self-power the facility. The remaining product is a charred, porous material made of a more stable form of carbon. These unique properties have made biochar a sought-after agricultural amendment in recent years, but the use of biochar is an age-old practice which was used to create “terra preta” in the Amazon Basin thousands of years ago.

What makes biochar so appealing? Many agricultural benefits of biochar are similar to the benefits of using other kinds of organic matter. The addition of biochar can increase a soil’s ability to hold nutrients, retain water and foster biological activity, especially in sandy, acidic soils. Saffron and Person also reminded listeners that nutrient and physical components of the original material remain in the “charred” version, which makes various kinds of biochar unique. Biochar made from poultry litter, for example, has a much higher concentration of phosphorus than biochar made from pine—which users should not forget when making their nutrient plans. Unlike other forms of organic matter, biochar is made of a more stable form of carbon which can be appealing to people interested in increasing the carbon content of their soil through “carbon farming” practices.

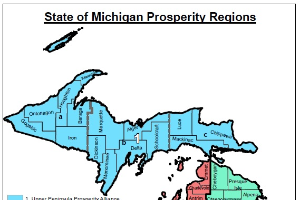

While the potential of biochar is substantial, many questions remain, hence the creation of the GLBN. The GLBN is a grant-funded organization established in fall 2021 through Project GREEEN. The organization works throughout the Great Lakes region to support research and provide science-backed information on biochar use. The GLBN also acts as a connector of different stakeholders in the industry to address the market and production challenges of such a new product.

Management recommendations are under development, though the GLBN has some general guidance when using biochar in your fields. Biochar can be applied to the field through broadcasting, banding or incorporation. However, the delicate structure of biochar can quickly make it a dust hazard, so a pelleted version would be the preferred form for land application. The application rate can have a wide range—from 0.05 tons per acre per year to 89 tons per acre per year, with 2-22 tons per acre per year being a common rate found in literature. Currently, the cost of biochar can be anywhere from $80 per ton to over $1,000 per ton. The economic feasibility of applying biochar depends on how close the land is to a biochar production facility. With so few production facilities in Michigan right now, this dramatic range may be the norm for the time being. However, Person and Saffron suspect that market stability and increased demand will occur as biochar gains regulatory parameters and industry investment.

Saffron emphasizes that biochar is like any other product or farm management decision. “It’s not like every time you add biochar you can expect good things to happen—it can be deleterious if not used well.” One of the most common concerns Person hears about biochar is the heavy metal concentrations that can be found in the material. “The quality of the [stock] dictates the quality of the product,” Person explains. For example, a plant’s accumulation of heavy metals or alkaline metals, such as magnesium or sodium, will remain in the biochar product even after processing. When applied to a field, these contaminants can be released into the soil.

Thankfully, guidance on biochar use is growing. In guides from the Pacific Northwest Biochar Atlas, users can find ranges and limits for heavy metal concentrations in various biochar products. The Michigan Natural Resource Conversation Service (NRCS) is also working to provide tools, policies and considerations for agricultural biochar use.

For even more guidance, or if you are interested in the GLBN, reach out through email, the GLBN website, or social media (Facebook or Twitter). To learn about using biochar well, the economic possibility of local biochar industries and more, listen to the full episode!

Listen here

To hear this podcast episode and more, follow the “In the Weeds” podcast from the MSU Extension Field Crops team! We discuss pressing issues and upcoming trends in agriculture with farmers, agribusiness professionals, and Michigan State University Extension educators. New podcasts are posted every week. To receive notifications for new episodes, please subscribe to our feed on Apple Podcast or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Print

Print Email

Email