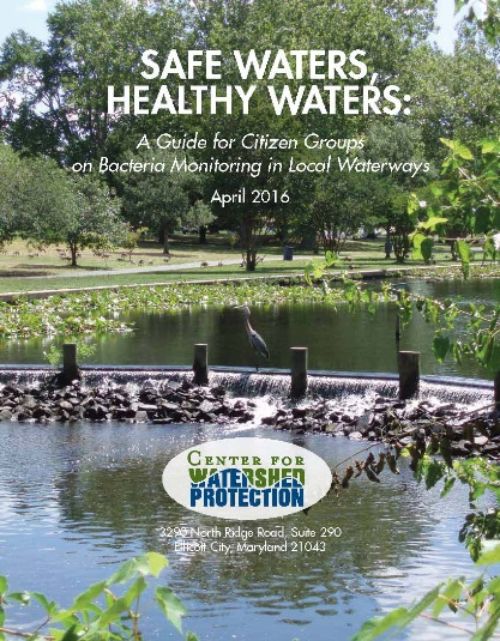

New guide to assist with citizen water monitoring programs

The Center for Watershed Protection has produced an online guide to assist groups in identifying goals and developing a monitoring program to achieve improved water quality in local waterways.

Michigan has approximately 36,000 miles of rivers and streams, over 11,000 inland lakes and nearly 3,200 miles of Great Lakes shoreline. Many of these water bodies are used for a number of purposes, including recreation. However, some of these waters are contaminated and can be a health risk for swimming, surfing, tubing and water play along the beaches. A 2015 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimate shows that 39 percent of the nation’s assessed rivers and streams and 13 percent of assessed inland lakes do not meet standards to allow for recreational uses.

There are many point (known) and non-point (unknown) sources of pollution in water bodies, but one of the most common pollutants is bacteria. While bacteria are naturally occurring in water, fecal bacteria is not and are harmful to humans. Fecal bacteria are microorganisms found in the intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals including humans. Ingesting fecal bacteria can result in a variety of illnesses from the relatively minor gastroenteritis to upper respiratory infections to more serious diseases.

Bacteria can enter local water bodies through a number of indirect and direct avenues, including storm water runoff, illicit connections to storm sewers, combined and sanitary sewer overflows, illegal dumping, failing septic systems, marine sanitation activities and wildlife and domestic animals.

In 2012, under authority of the Clean Water Act, the Recreational Water Quality Criteria was released by the EPA. This criteria is designed to protect water bodies that have been identified as primary contact recreational use where a high degree of bodily contact is likely, such as swimming, bathing, water skiing, surfing, tubing and general water play.

The Center for Watershed Protection has recently released a guide for bacteria monitoring. The Safe Waters, Health Waters: A Guide for Citizen Groups on Bacteria Monitoring in Local Waterways, published in April 2016, can assist groups in developing a bacteria monitoring program with a focus on techniques that are simple, reliable and low-cost. It can provide guidance to groups on how to identify, narrow sources and communicate about contamination.

The guide is divided into four sections:

- Background on Bacteria in Local Waterways outlines the basics of water quality, sources of bacteria in water, the role of citizens in water quality monitoring and additional resources to provide more information.

- Designing Your Bacteria Monitoring Program includes how to design a monitoring program based on the goals the group wants to achieve.

- Investigating Potential Pollution Sources will help people understand the steps needed for further investigation of known or suspected pollution sources, while pointing out the actions available to citizen groups.

- Sharing Findings and Taking Action covers the importance of sharing monitoring data, using education and outreach to address the problems, and developing relationships with local officials to take action.

The guide also includes a number of case studies from groups having a variety of different water quality goals.

Print

Print Email

Email