New transportation act allows greater flexibility in street design

The new FAST Act allows local engineers and planners to design lanes and configurations with greater flexibility to focus on pedestrians and bicyclists.

On Dec. 4, 2015, President Obama signed a new five-year transportation bill after the US House and Senate overwhelmingly approved it one day prior. The bill is referred to as the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, or the FAST Act and is 1,300 pages long calling for $305 billion in spending. While a summary of the new law is beyond the scope of this Michigan State University Extension news article, there is at least one noteworthy change that will help Michigan cities (and those in other states) more effectively engage in placemaking.

Placemaking is about creating places where people feel safe and comfortable, and where economic activity and socializing with others are natural outcomes of good design. Since placemaking has a lot to do with the quality of public spaces, the right-of-way is an important contributor to (or detractor from) sense of place. City streets that prioritize the pedestrian and bicyclists over, or equal to, the automobile tend to have a stronger sense of place than streets designed with motorists principally in mind.

The FAST Act allows for more flexibility in city street design. Prior to the new law, city planners and engineers were required to follow the standards used by state transportation department engineers. Typically, this was the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) ‘green book’, which is the principal national transportation design resource. Despite the fact that research shows 10 foot wide travel lanes on city streets are safer than 12 foot travel lanes, locals could not implement such street design without the consent of the state transportation department.

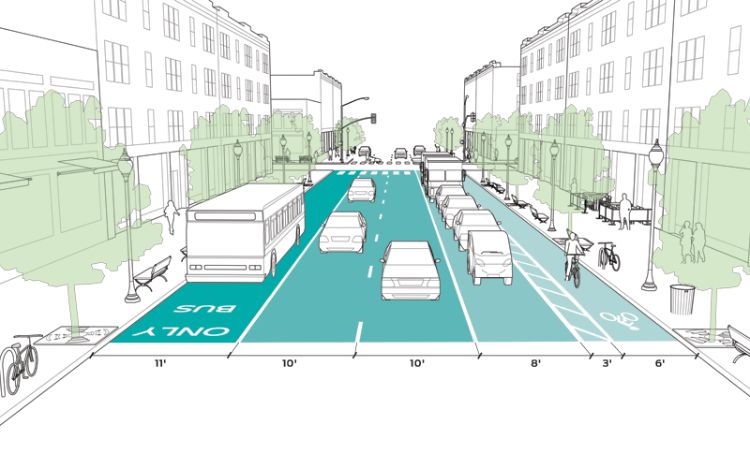

The new transportation act changes this. Now, federally funded street projects where local planners and engineers have the lead can be designed based on a different set of design standards than the AASHTO green book. So long as the Federal Highway Administration approves the other design standards, such as the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) Urban Street Design Guide and the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Designing Urban Walkable Thoroughfares resource, engineers and planners can design lanes and configurations with greater flexibility to focus on pedestrians and bicyclists. Both of the above guidelines are oriented towards the creation of more walkable and bikeable urban environments. So, the FAST Act should allow local planners and engineers to more easily design and implement streets that reinforce other placemaking efforts – streets that are considered Complete Streets.

Michigan communities have been required to adopt locally tailored Complete Streets policies since August 2010 after amendments were made to the State Trunk Line Highway System Act and the Michigan Planning Enabling Act. Today, there is strong evidence that Complete Streets provide concrete benefits to communities including safety, reduction in vehicle miles traveled, and positive impacts on local economies, and now it will be easier for Michigan communities to implement such policies in a way that reinforces other placemaking efforts.

Print

Print Email

Email