Steelhead declines spur discussion of research and management options

The first Steelhead Fishery Workshop addressed questions related to steelhead harvest, bag limits, stocking strategies, and diet.

The steelhead is a prized gamefish that provides a unique contribution to recreational fishing in Michigan. Although steelhead do most of their feeding and growing in the Great Lakes, many are caught in rivers. Unlike salmon, steelhead can spend many months in a river environment. The peak steelhead run occurs in early spring for most rivers, but fall runs can also be strong and overwintering fish can provide decent open water fishing through the coldest months of the year. Skamania strain steelhead even provide a summer run on some rivers like the St. Joseph and Manistee.

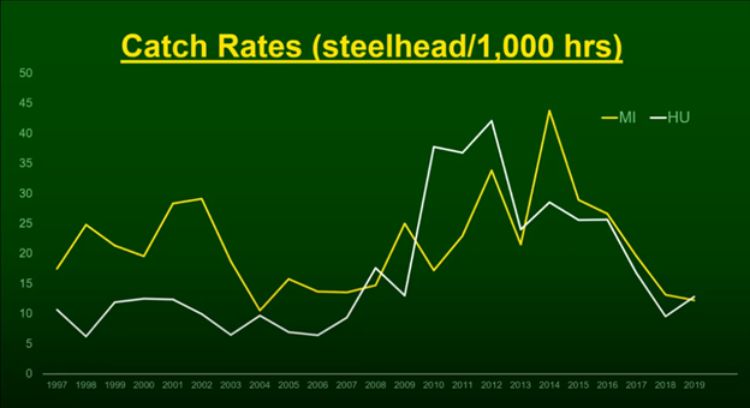

On many rivers, steelhead anglers have noticed a decline in their catch rate in recent years. Seasoned pros who have kept fishing journals for decades are noting more and more blank pages. The timing and strength of steelhead runs can be highly dependent on water temperature and river flow, but people are concerned that recent low catch rates might be due to something other than the normal weather-based fluctuations.

On Feb. 22, 2021, Michigan Sea Grant hosted a Steelhead Fishery Workshop featuring speakers from Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Michigan State University to review past and current research projects and management issues. The goal was to bring river anglers together with fishery professionals to explore some potential causes and highlight needs for future research. While definitive answers aren’t available yet, several questions were addressed.

Harvest and bag limits

Michigan DNR’s Statewide Angler Survey Program conducts creel surveys to estimate angler harvest and effort. Tracy Claramunt, who leads the program, provided an overview of steelhead harvest patterns at the workshop. Great Lakes and rivers were covered. Many Great Lakes ports are surveyed on an annual basis while rivers are only sporadically covered due to the logistical challenges and extra costs. For this reason, we do not have a complete accounting of steelhead catch, harvest, or effort in Michigan rivers.

Even so, Claramunt shared creel results that suggest Great Lakes anglers catch far fewer steelhead than river anglers. The AuSable River, a tributary of Lake Huron, was surveyed in 2009. Anglers caught roughly 30,000 steelhead from the AuSable in 2009, which was around six times more than the total steelhead catch in all Michigan waters of Lake Huron that year. Similarly, the steelhead catch in the Manistee River was higher than all Michigan waters of Lake Michigan in 2015.

The long-term health of the steelhead population is maintained through a balance of stocking and natural reproduction. Although steelhead will not be stocked in 2021 due to COVID-19 restrictions that prevented egg take in 2020, DNR’s Lake Michigan Basin Coordinator Jay Wesley reported that the DNR plans to reinstate former stocking levels in 2022.

Natural reproduction is limited by the scarcity of suitable spawning and nursery habitat. Spawning steelhead require the right mix of hard gravel or cobble substrate, high gradient, and clean, cold water for development of eggs and young. Since prime habitat is uncommon in streams accessible to steelhead, it stands to reason that only a small number of adult steelhead can fully saturate the available habitat in any given year.

This means that lower bag limits probably won’t affect the long-term prospects for the population, Wesley explained (see fact sheet for additional details). Bag limits might serve other functions, though. Although lowering the bag limit probably won’t result in higher steelhead numbers in years to come, it could allow for more ‘recycling’ of steelhead if fish are released to be caught again.

Some anglers prefer to catch-and-release all steelhead and others consider keeping fish for the table an essential aspect of fishing. Wesley welcomed feedback and mentioned that a bag limit reduction might be considered if there was broad consensus among different groups of anglers. The current bag limit for steelhead is essentially three fish per day in most waters, but check the Michigan Fishing Guide for full details on seasonal closures, harvest limits, and length restrictions for the waters you fish.

Claramunt’s presentation also touched on possible impacts of changing bag limits. She noted that Great Lakes recreational salmon and trout anglers fishing from boats catch three or more steelhead in less than 1% of trips. Pier and shore anglers fare better, with roughly 9% catching three or more. Of course, the number of pier and surf anglers is far lower than boat or river anglers. In the AuSable River, catch rates were far higher with around 60% of anglers catching three or more steelhead in 2009.

Catch rates undoubtedly vary dramatically from river to river and year to year, but this suggests that reductions in bag limits will do more to limit harvest in rivers than in the Great Lakes. Trends in voluntary catch-and-release can also vary. Around two-thirds of steelhead were released in the Manistee River in 2015, while anglers on the AuSable released over 99% of steelhead in 2009.

Stocking strategies

Jory Jonas, a biologist at DNR’s Charlevoix Fisheries Research Station, presented an overview of previous studies that addressed the impact of stocking location and strain on steelhead survival. Jonas provided a comprehensive comparison of Skamania and Michigan winter strain steelhead performance in the St. Joseph and Manistee rivers. Both strains provided a similar proportion of trophy-sized steelhead. Michigan winter strain steelhead stocked in the Manistee River were more likely to be caught by anglers than Skamania stocked in the Manistee, regardless of the port fished.

Skamania stocked in the St. Joseph River were more likely to be caught at the port of St. Joseph, but all other ports saw a better return-to-creel from Michigan winter strain fish stocked in the St. Joe River. This means that Michigan winter strain fish generally survive better and contribute more to Great Lakes fisheries, but Skamania provide a strong localized fishery in St. Joseph in addition to providing summer (and also fall) angling opportunities in rivers.

According to an earlier study led by Paul Seelbach, steelhead stocked in the Grand River system in 1988, 1989, and 1990 were much more likely to be caught by anglers if they were stocked close to Lake Michigan. Survival was much higher for steelhead stocked at Grand Haven, near the mouth of the river, than in upstream locations and tributaries. Stocking locations in the St. Joseph River were also included in Seelbach’s study, but results were less conclusive.

A later study included river systems stocked 1996-1999. Again, the St. Joseph River did not find any clear benefit to stocking upstream vs. downstream locations. In the Muskegon River and AuSable River, upstream stocking sites actually produced better steelhead survival rates. A downstream stocking site in the Sturgeon River resulted in better survival than an upstream site, but sample size was low.

Based on these findings, steelhead are often stocked in upstream areas and tributaries to provide a variety of river fishing opportunities. The success of upstream vs. downstream stocking locations may also change over time, or vary from river to river. The Grand and St. Joseph are both large, dammed rivers that are home to a variety of resident predatory fish (bass, walleye, catfish, pike) that may take a toll on stocked steelhead. Still, the St. Joseph River saw no benefit to downstream stocking in either study. The Grand did show stronger survival downstream, but was only included in the earlier study. Upstream and tributary stockings continue to be important for the Grand to support fisheries in popular streams like the Rogue River and in upstream sections of the mainstem.

Addie Dutton, DNR biologist in the Southern Lake Huron Management Unit, gave an overview of stocking sites and stocking rates in Lake Huron rivers and harbors. Dutton also noted that the Rifle River, AuGres River, and the East Branch of the AuGres support natural reproduction of steelhead, although the extent of wild production is not known. The DNR is also working with the Lake Huron Fisheries Citizen’s Advisory Committee to protect stocked steelhead from predation by exploring possibilities for alternate timing and location of steelhead stocking events. Since steelhead will not be stocked in 2021, changes to stocking protocols will not be implemented this year.

Steelhead diet

The collapse of alewife in Lake Huron around 2004, and their decline in Lake Michigan over the past decade, had massive impacts on Chinook salmon. Chinooks all but disappeared from central and southern Lake Huron, and fishery managers around Lake Michigan dialed back stocking in 2012 and again in 2016 to prevent a similar collapse.

Conventional wisdom holds that steelhead are more resilient, though. Unlike Chinook salmon, steelhead will readily switch to other prey items if alewife disappear. Brian Roth of MSU has been studying trout, salmon, and walleye diets in both lakes since 2017, and his findings both reinforce and challenge some of the old assumptions.

Steelhead are now feeding primarily on terrestrial insects in Lake Huron, while rounding out their diet with rainbow smelt and other fish. In the near absence of alewife, Lake Huron steelhead are still able to make a living. The diet of Lake Michigan steelhead is in stark contrast; although some steelhead stomachs did contain large numbers of insects, alewife accounted for over 90% of the steelhead diets in 2017, 2018, and 2019. This means that alewife provide the vast majority of energetic needs for Lake Michigan steelhead. Steelhead diet in Lake Michigan also follows a seasonal pattern each year, with fish consuming more insects in spring and shifting to alewife in summer.

In an earlier presentation from December 2020, Jonas also noted that alewife numbers have a close correlation with steelhead growth in Lake Michigan. In fact, steelhead growth can be even more dependent on large alewife abundance than Chinook growth. There is a clear link between alewife abundance and steelhead growth, but it is not clear whether steelhead numbers also fluctuate as a result of changes in alewife numbers.

What can I do to help?

Biologists would like your help collecting data on steelhead in Michigan rivers and in the Great Lakes to better understand how stocked and wild-spawned steelhead contribute to fisheries around the state. Dan O’Keefe with Michigan Sea Grant provided an overview of volunteer data collection efforts utilizing the Great Lakes Angler Diary.

Details on the volunteer data collection program are available online. The program includes following the steps below:

- REGISTER at GLanglerdiary.org or download the iOS app.

- RECORD every river steelhead trip taken.

- MEASURE each and every steelhead caught.

- CHECK for fin clips and other marks.

At the end of the season you will be asked to take a short survey and verify that your information is complete. It is important to record data on every trip taken and every steelhead caught in order to avoid bias. Measuring every fish to the nearest quarter inch is best, but wading anglers who fish alone and release their catch can also estimate the size of fish as <20 inches, 20-28 inches, and >28 inches.

If you catch a steelhead with a clipped adipose fin, you can also help biologists figure out where it was stocked by submitting the heads or snouts for tag extraction. The Great Lakes Salmon Initiative (GLSI) coordinates a rewards program that gave away 33 prizes during the 2020 season. The CWT tag reward program will be offered by GLSI again in 2021. All CWT heads turned in during 2021 from steelhead, Chinook salmon, Atlantic salmon, coho salmon, and brown trout will be eligible for $100 prizes via random drawing in the winter of 2022 after all returned micro-tagged heads are processed.

You can also contribute to the Huron-Michigan Predator Diet Study by collecting stomachs from steelhead, other trout and salmon, and walleye from lakes Michigan and Huron. The 2021 season may be the final year for data collection, and it is particularly important for volunteers to collect stomachs in early spring and late fall since biologists conduct the majority of their sampling during summer. Along with heads and snouts, stomachs can be bagged, tagged, and deposited at freezers located at access sites in most ports. Be sure to label and bag each sample individually since biologists must be able to match information from the data tag with an individual stomach or snout.

Although we do not have solid answers to all of the questions regarding recent declines, volunteer efforts like these will help biologists learn more about Michigan’s steelhead populations.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research, and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This report was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA180AR4170102 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email