Building Climate Resilience in Vineyards: Carbon Sequestration as a Tool for Sustainable Winegrowing

DOWNLOADDecember 19, 2025 - Esmaeil Nasrollahiazar, Vahid Rahjoo, and Alexa Kipper

This fact sheet provides Michigan grape growers with practical, research-based strategies to strengthen vineyard resilience by building soil carbon. Climate change is creating new challenges — from shifting yields to increased disease pressure — while markets and consumers increasingly demand sustainable practices. By outlining the science and practices behind soil carbon management, this resource highlights both environmental and economic benefits, showing how carbon-focused approaches can improve vine health, enhance fruit quality, and open opportunities such as certification and carbon markets. In doing so, it positions vineyards not only to adapt to climate variability but also to contribute actively to climate solutions.

Introduction

Climate change presents both challenges and opportunities for the wine industry. Viticulture is highly sensitive to shifts in temperature, rainfall, and extreme weather, and growers are already seeing impacts on vine performance, disease pressure, and fruit quality. At the same time, vineyards are uniquely positioned to contribute to climate solutions. One of the most effective strategies for climate change mitigation is increasing soil organic carbon, which improves vineyard resilience while helping mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Importantly, building soil carbon creates ripple effects far beyond vine health. Practices that increase carbon reduce atmospheric CO₂, improve watershed health by reducing nutrient runoff, and foster more resilient plants that require fewer chemical inputs. In this way, vineyard soil management contributes not only to wine quality and farm viability, but also to climate mitigation, water quality, and public health.

Key Messages for Growers

- Soil carbon equals soil health. More carbon means better water-holding capacity, erosion control, disease suppression, and nutrient cycling.

- Carbon is a tool for both adaptation and mitigation. Practices that build carbon help vineyards withstand climate extremes while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Practical strategies exist. Cover cropping, reduced tillage, organic amendments, biomass retention, and biochar all contribute to stronger soils and healthier vines.

- Microbes matter. Microorganisms, fungi, and root exudates drive long-term carbon storage and support vine nutrition.

- Economic value is real. Higher fruit quality, reduced chemical inputs, and potential carbon market participation make soil carbon an investment in both resilience and profitability.

- Growers can lead. By adopting carbon-focused practices, vineyards can demonstrate how agriculture contributes to climate solutions while producing exceptional wines.

Why Focus on Soil Carbon?

Soil carbon is the foundation of soil health. By storing carbon belowground, vineyards gain multiple benefits: improved soil structure, enhanced water-holding capacity, reduced erosion, increased disease suppression, and higher microbial activity that drives nutrient cycling. For grape growers, this translates to healthier vines, more consistent yields, and improved fruit quality.

Soil Organic Matter (SOM) vs. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC)

Soil organic matter (SOM) is the total pool of organic material in soils, including living organisms, fresh residues, decomposing fragments, and stabilized compounds. Soil organic carbon (SOC) is the carbon fraction of this pool, typically making up 50–58% of SOM by weight. While SOM reflects overall soil fertility and biological activity, SOC is the fraction most directly tied to carbon sequestration and climate goals. In practice, building SOM also builds SOC — but distinguishing between the two helps clarify whether we are talking about soil function (SOM) or climate mitigation (SOC).

Understanding Soil Carbon Pools

Soil carbon exists in multiple fractions or “pools,” each with different stability and functions:

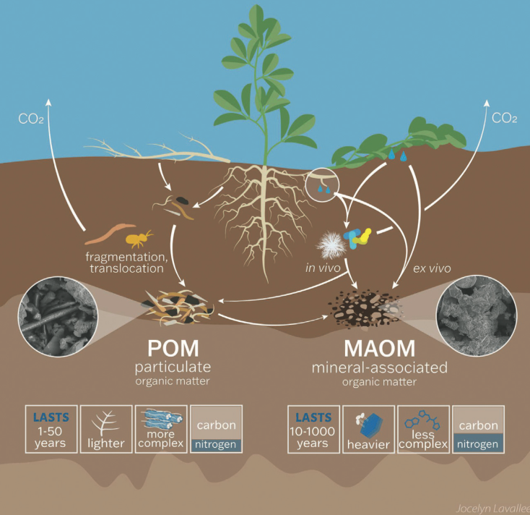

- Particulate Organic Matter (POM): Larger fragments of plant and root material in the early stages of decomposition. POM provides food for microbes and drives short-term nutrient cycling, but it is highly vulnerable to disturbance and rapid oxidation.

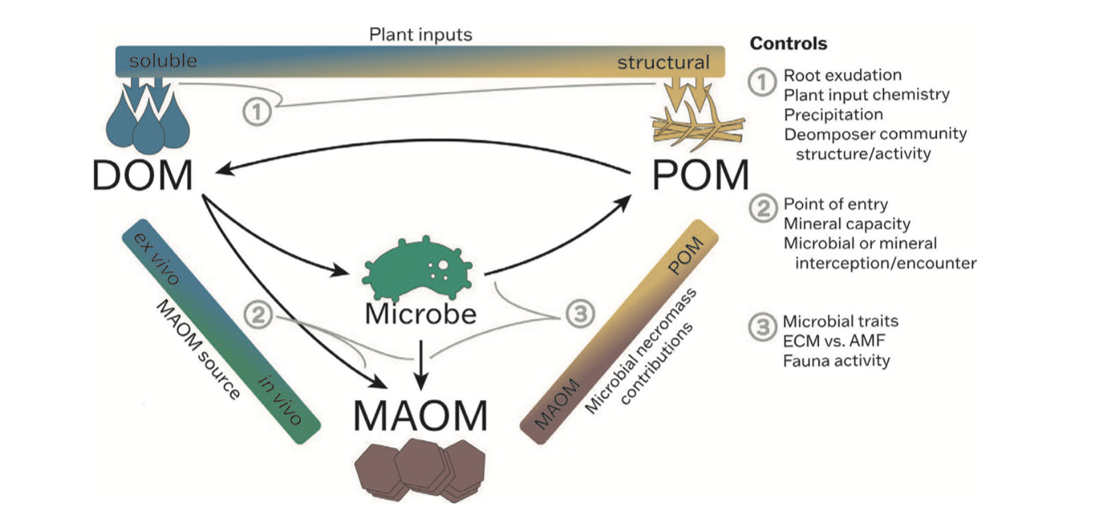

- Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM): Small, soluble compounds released by roots and microbes during decomposition. DOM is highly mobile, moving with water through the soil profile, where it fuels microbial activity and influences nutrient availability.

- Mineral-Associated Organic Matter (MAOM): Stable carbon formed when microbial byproducts and plant-derived compounds bind tightly to clay and silt particles or are physically protected within aggregates. Because it is less accessible to microbes, MAOM can persist for decades to centuries, representing the primary pathway for long-term sequestration and lasting soil fertility.

Microbial Contributions to Carbon

Microorganisms are the architects of soil carbon stabilization:

- Microbial necromass, the remains of dead microbial cells, makes up nearly half of soil organic matter. When these residues bind to minerals, they form the backbone of mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM), the most stable carbon pool.

- Fungi, especially arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), play a central role in carbon stabilization.

- Root exudates, including sugars, organic acids, and other compounds released by grapevine and cover crop roots, fuel microbial activity and growth. These exudates are especially critical for forming soil organic matter at depth, where microbial activity transforms them into necromass that binds to minerals and persists for decades to centuries. By fueling microbial communities belowground, root exudates help build carbon stores that are both stable and resilient to loss.

Practices That Enhance Soil Carbon

The key to increasing soil carbon is tipping the balance toward greater inputs and reduced losses. In vineyards, the most effective strategies are:

- Cover Cropping and Root Systems: Continuous living roots from vines and cover crops provide exudates and organic residues that fuel microbes, improve soil structure, and stabilize carbon deeper in the profile.

- Minimal Soil Disturbance: Reducing tillage preserves aggregates, slows carbon losses, and protects fungal networks.

- Organic Amendments: Compost, mulches, and manures add carbon directly and feed microbes. Because many industrial composts lack a full soil food web, pairing them with microbial inoculants (compost teas, indigenous microorganisms) helps restore biology and promotes stable carbon formation.

- Biochar: A highly recalcitrant form of carbon that persists for centuries. Biochar improves cation exchange capacity, water retention, and microbial habitat, especially when combined with organic inputs that feed biology.

- Biomass Retention: Returning prunings, leaf litter, and other organic residues to the vineyard floor keeps carbon cycling onsite.

Integrating Regenerative Agriculture Practices

Adopting regenerative agriculture practices can further enhance carbon sequestration and soil health in vineyards:

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees and shrubs into vineyard landscapes can increase carbon storage, enhance biodiversity, and provide additional ecosystem services.

- Rotational Grazing: Managed grazing of cover crops by livestock can aid in nutrient cycling and reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Diversified Plantings: Incorporating a variety of plant species can improve soil structure, enhance microbial activity, and increase resilience to pests and diseases.

Carbon and the Soil Food Web

Carbon is the currency of the soil food web. Labile inputs like exudates, POM, and DOM fuel bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and nematodes. In turn, these organisms cycle nutrients back to vines while stabilizing carbon through necromass, aggregate formation, and mineral associations. Practices that support microbial diversity — fungal-rich compost teas, mycorrhizal inoculation, reduced chemical inputs — amplify both soil carbon storage and vine health.

The Business Case

Building soil carbon benefits growers, wineries, and consumers alike. Consumers increasingly demand sustainably produced, low-carbon wines, and international markets may soon require carbon reporting or compliance with emissions thresholds. Certification programs and carbon markets offer potential financial incentives, provided growers follow proper verification and reporting standards.

Importantly, carbon accounting must be transparent: carbon sequestered in soils cannot be “double-counted” — credits used to offset a winery’s own emissions cannot also be sold externally.

Beyond market incentives, soil carbon investments deliver direct on-farm value. Increasing organic matter improves water-holding capacity, buffers against drought and heat, and reduces erosion and runoff during heavy rainfall events. These benefits strengthen vineyard resilience at a time when climate risks are intensifying, making soil carbon both an environmental and economic imperative for long-term vineyard viability.

From Adaptation to Mitigation

Traditionally, the wine industry has emphasized adaptation — adjusting vineyard practices to cope with changing weather patterns. Adaptation will remain essential, but there is now a growing need to also address mitigation: actively reducing emissions and building carbon sinks.

More than half of a wine bottle’s carbon footprint comes from packaging and transport, yet vineyard practices also play a meaningful role. Fertilizer use, tillage, and other soil management decisions influence both emissions and sequestration potential. By integrating carbon-focused practices, vineyards can shift from being passive responders to climate change toward becoming active contributors to its solution.

Conclusion: Carbon as a Soil Health Strategy

Soil carbon is more than a climate metric — it is the foundation of soil health and a driver of global sustainability. By managing vineyards to increase inputs of labile carbon while promoting the formation of stable pools like MAOM, growers can enhance fertility, improve fruit quality, and build resilience against climate extremes. At the same time, carbon-focused practices reduce atmospheric CO₂, improve water quality, and decrease reliance on chemical sprays by fostering healthier, more resilient plants. In this way, investing in soil carbon creates cascading benefits that extend from vineyard productivity to ecosystem services and climate solutions. The wine industry is uniquely positioned to lead by showing how agriculture can both safeguard the planet and produce exceptional wines.

Print

Print Email

Email