Local government has an important role for water quality protection: Part 2

State and federal regulations help protect water resources but does not do the whole job. Local government has an important role also – key to retaining important habitat on lake’s and river’s edge.

Local governments have a very important role to play in the protection of surface water, ground water, drinking water, and wetlands, often filling the gaps in state and federal regulations. If local government, with local zoning does not do so, those gaps may not be addressed. There are various state and federal laws designed to protect water quality. But relying only on state laws may not do a complete job and is not as successful at being preventative as zoning can be.

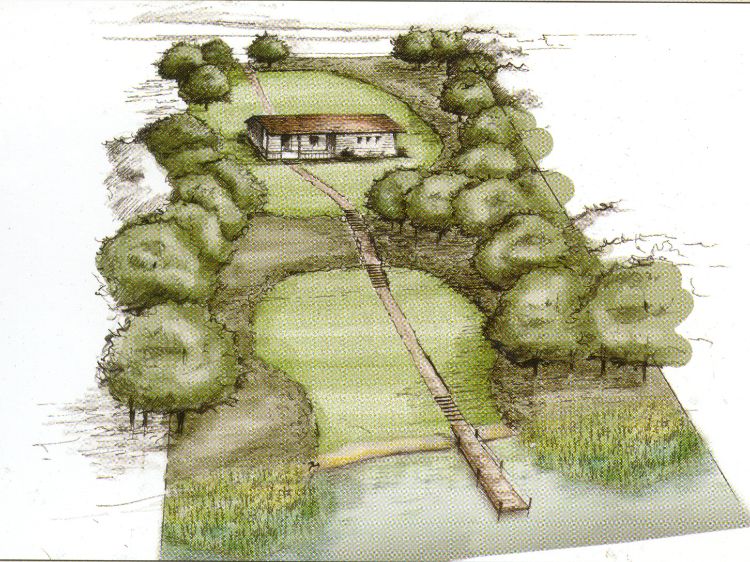

In part one of this series of articles, “Local government has an important role for water quality protection,” the focus was on how to determine the amount, or distance, of greenbelt buffer along lakes and rivers. That distance, and the plant material retained in the greenbelt varies depending on the goals. The goal may be to prevent lawn and septic pollution from getting into the lake or river, or it may also include aesthetics or to protect natural habitat.

Protecting natural habitat can be important economically (it is a natural place that draws tourists and creates rural place for economic development), as well as many scientific-based reasons. But science does not always resonate with people when deciding about habitat and natural resource protection. But the article "A Second Life for Trees in Lakes: As Useful in Water as They Were on Land" by Michael A. Bozek, University of Wisconsin’s Center for Land Use Education at Stevens Point said it better than I could:

“Ten thousand years ago, a tree grew on the shore of a lake somewhere in North America. For 140 years or more, fish swam in its shade and insects hatched on its branches and leaves; some were eaten by birds, some fell into the water to be eaten by fish, and some survived to continue the cycle of life. Birds nested and foraged in the tree’s branches, kingfishers dropped like rocks, propelled by gravity to their next meal, while eagles perched amongst its highest branches. A wood frog chorus would start each evening in spring near the first crotch, and red squirrels would chatter for whatever reason red squirrels chatter. Then one day it happened: after years of increasing decay near the end of its life, the tree snapped at the butt during a windstorm and fell with a thunderous crash into the lake ending 140 years of silence and quiet rustling, punctuated by a single, quick, loud finale. Within a minute, the waves that had acknowledged the tree’s entry into the water subsided, and all was quiet again.

“Now the tree began its second life…in the lake. Within hours, crayfish crawled beneath its partially submerged trunk, to be followed by a mudpuppy and tadpoles, while minnows and small fish hovered within the lattice of its branches. Within days, logperch, darters, sunfish, bass, burbot, pike and even walleye and muskellunge had also entered the complex network of the newly established community. Algae and diatoms began establishing colonies, while dragonfly nymphs and mayflies followed to forage among the branches. A wood duck competed with a softshell turtle for basking space on the bole that once contained its nest site cavity. Herons, green and blue, alternated use as well: the bole presented a fine place to access the fish below. Use of the tree by a variety of organisms would continue again for much longer than its life on land. Remarkably, the tree might last another 300 to 600 years, slowly changing shape over time as it yielded to Father Time. Different organisms continued to use the tree until its cellulose had completely broken down and its chemical constituents had been fully integrated into the web of life in the lake. . . .

“Over time, humans have altered riparian areas of lakes at rapid rates across a large portion of the landscape: first, by logging, and more recently, by lakeshore development. In the Upper Midwest, forest stands in previously logged areas have more or less recovered and now sustain healthy second-growth forests. In contrast, many riparian owners along developed lakes have removed some or all of the trees from their lakefront property and the water. Where landowners continue to remove new understory trees and seedlings, they prevent recovery of shoreline areas to their natural state.

“The rate and pattern in which trees fall in a lake depend on the stand of trees in the riparian area and activities of landowners. Trees in lakes tend to be most abundant (dense) in smaller lakes with undeveloped shorelines. Larger lakes have higher wind and wave energy which can break up trees faster and transport them offshore to deeper water. Greater development often results in landowners actively removing trees from shorelines and manicuring riparian areas. . . .

“Fish use submerged trees in a variety of ways. Many species spawn on, adjacent to, or under trees. The trees provide cover helping some species protect their incubating brood. For example, smallmouth and largemouth bass preferentially build spawning nests near submerged trees, particularly large logs, while rock bass place them next to or under logs. Because male bass and sunfish defend their eggs and young in nests, placing nests adjacent to or under submerged trees reduces the nest perimeter that they need to defend against predators. Once young have left the nest, newly hatched smallmouth bass will often inhabit submerged trees. A decline in submerged tree habitat has been linked to reduced abundance of young smallmouth. Yellow perch use submerged wood along with aquatic vegetation to lay eggs; long ribbon-like strands that can often be seen draped on them in early spring. Three studies have found a decline in yellow perch abundance when trees were removed from lakes.”

--(Footnotes and citations omitted)

A summary of the article can be found in the spring 2015 "Land Use Tracker" published by the University of Wisconsin (Stevens Point) Center for Land Use Education.

MSU Extension offers training programs and additional materials about water protection, protecting shorelines with use of natural shoreline erosion controls, and planning and zoning approaches to the topic. Contact your nearest land use or natural resource educator to sponsor such training in your county.

Other articles in this series:

- Local government has an important role for water quality protection: Part 1; local regulation is needed and what distance for setbacks, greenbelts and buffers.

- Local government has an important role for water quality protection: Part 3; State and federal regulations help protect water resources but does not do the whole job. Local government has an important role also – buffers and greenbelts are enforceable and are not property takings.

Print

Print Email

Email