Management recommendations for soybean fields infested with white mold

Manage this year’s white mold inoculum to reduce the incidence and severity of white mold in future soybean crops.

This summer’s cool and wet weather created conditions favorable for the development of white mold. Consequently, the disease has infected soybean fields across the state (Photos 1 and 2) and resulted in the development of significant amounts of white mold inoculum that can impact future crops. With careful management, producers can significantly reduce the amount of white mold inoculum produced this year that will be available to infect future susceptible crops grown in the infested fields.

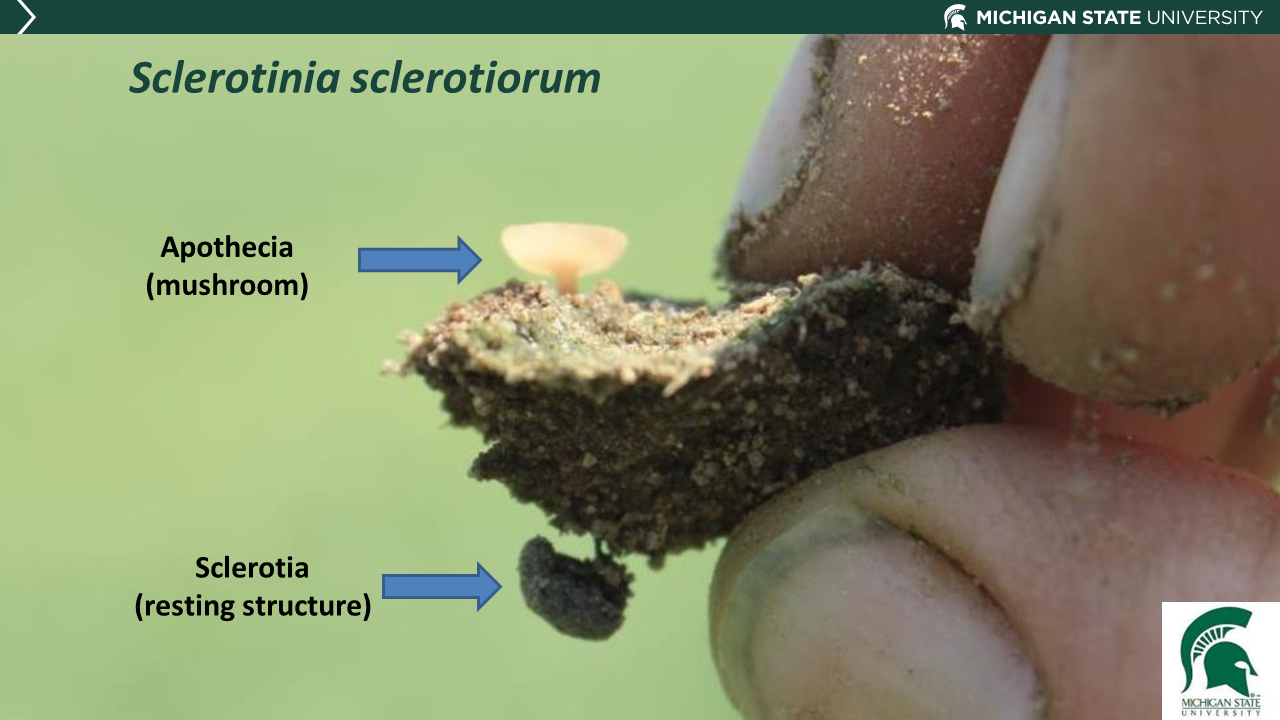

White mold inoculum is contained in small, black survival structures called sclerotia. The sclerotia are produced on and in the stems and pods of infected plants and resemble rat droppings (Photo 3). Sclerotia can germinate to produce apothecia (mushrooms) at the soil surface and up to a depth of 2 inches under favorable conditions (Photo 4). However, they can survive for five to eight years when incorporated deeper in the soil with tillage operations. Sclerotia management should be the focus for managing white mold at this stage in the growing season.

Keeping long-term field records is the first step to managing white mold. Identify heavily infested fields or areas of fields that are heavily infested and record the variety, planting population, planting date, fertilizer/manure applications, irrigation timing and rates and row spacing for each of these fields. This information will help you track fields or areas having the most potential to develop white mold in the future and identify management practices that can be changed to reduce white mold pressure in future soybean crops.

Tillage can be an important method for managing sclerotia, and crop rotation plans should be considered when making tillage decisions in severely infested fields. No-tillage is recommended when the next crop is not susceptible to white mold. With no-tillage, all the sclerotia produced by this year’s infestation will remain on the soil surface where they have the highest probability of germinating or degrading. When the sclerotia germinate in fields planted to a non-host crop, no infection occurs and the life cycle of the disease is terminated. Non-host crops vary in their ability to create favorable conditions for sclerotia germination. Information from Wisconsin showed that small grains produced a higher level of sclerotia germination than commercial corn and information from Iowa State University states that seed corn may not produce conditions favorable for sclerotia germination.

Tillage is recommended if the following crop is susceptible to white mold. Tillage operations that bury the sclerotia more than 2 inches deep will reduce the quantity of inoculum available to infect the following crop. However, the sclerotia will remain viable for at least five years and will be returned to the top 2 inches with subsequent tillage operations where they can germinate to produce apothecia and infect susceptible crops.

Producers can reduce the movement of sclerotia to non-infested fields by harvesting infested fields last and thoroughly cleaning the combine before entering non infested fields and when soybean harvest is completed.

Producers may also consider applying a biological control product such as Contans to fields having a history of severe white mold. This product contains Coniothyrium minitans, a naturally occurring fungus that attacks and degrades sclerotia in the soil. The products should be incorporated into the soil as uniformly as possible to a depth of 2 inches at least three months prior to initial soybean bloom. Fall applications of 2 pounds per acre have been the most effective for reducing the number viable sclerotia in the soil.

It is important to note that Contans will attack and degrade the sclerotia in only the top 2 inches of soil but will not eliminate all sclerotia. Tillage operations deeper than this should be avoided to prevent redistributing viable sclerotia into the top 2 inches where they can germinate and infect the succeeding susceptible crop.

Sclerotia are graded as foreign material and moldy beans are graded as damaged at delivery and both can lead to discounts. Because of this, producers should adjust combine fan and sieve settings to prevent them from reaching the clean grain tank. According to Marion Calmers, foreign material and moldy soybeans smaller than normal soybeans must be removed by the cleaning fan. Calmers recommends starting with a high fan speed and decreasing it until some soybean trash and sclerotia begin showing up in the clean grain tank and then he speeds the fan up a little (by an additional 50 RPM). Avoid setting the fan speed so high that marketable beans are blown out the back of the combine.

The following Michigan State University Extension resources provide essential information about using foliar fungicides to manage white mold in soybeans:

- Begin managing white mold in soybeans this spring

- Fungicide use for managing white mold in soybeans

- Equipping and Operating Sprayers to Control Insects and Diseases in Soybeans

A practical video on cleaning combines is available online at:

While the damage has already been done to this year’s soybean crop, producers can develop and implement plans for reducing the amount of white mold inoculum available to infect susceptible crops grown in the future.

This article was produced by a partnership between Michigan State University Extension and the Michigan Soybean Committee.

Print

Print Email

Email