Research Drilldown: Challenges in the milking parlor

The parlor is one of the key “bottlenecks”. Many producers try to find the balance between “parlor efficiency” and growing their operation. Learn more about challenges in the milking parlor.

Farms with at least 1,000 cows account for more than half of all cows in the U.S. dairy herd. More than two-thirds of the milk supply is produced by herds with more than 500 cows. To attain better milking productivity, dairy producers have invested considerable capital into milking systems. Depending on factors such as herd milk production and dairy markets, the timeline for the return on investment varies, which adds considerable pressure on farm finances.

In addition to herd size, milk production per cow has also increased, but milk is still harvested the way it has been for a century—prepping cows to stimulate oxytocin release and applying vacuum to the teat end within a double-chambered teat cup. Also, milking protocols that help prevent mastitis have become more accepted. Thus, the connection between the cow, producer and machine has been beneficial for the dairy industry and has allowed more milk to be harvested, with less labor, and better quality.

The key force that drives milking parlor operation for many dairies is the number of cows that are milked through the facility each day. Thus, the parlor is one of the key “bottlenecks”. Many producers try to find the balance between “parlor efficiency” and growing their operation. However, this has created other challenges, most notably employee availability, training and engagement due to fast paced, repetitive milk-harvesting tasks, as well as the demand for higher milk quality, and consumer concerns over the welfare of dairy cattle.

For many dairy producers, “keeping the cows on schedule” through the parlor is a frequent concern. This is especially the case where milking times for groups of cows are synchronized with cleaning of pens, feeding and other needs such as breeding. Most herds track parlor efficiency—for example, turns (loads) of the parlor per hour, number of cows milked per hour, number of cows milked per employee-hour of work, or milk harvested per hour (or shift, or day)—as their key measures of milking success. Thus, this is the primary goal for many dairy herds when it comes to milking cows. But are we missing something?

Milking efficiency vs. parlor efficiency

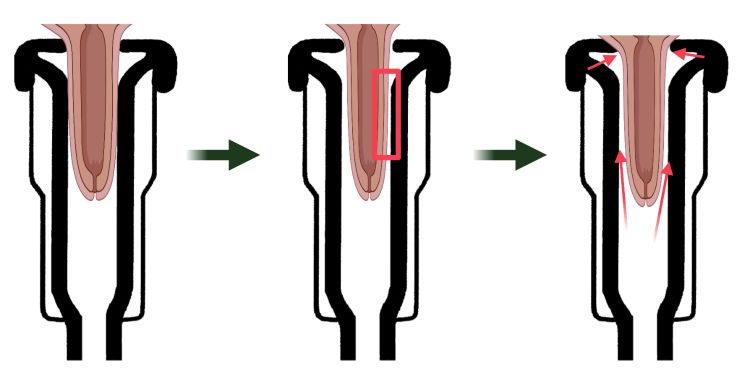

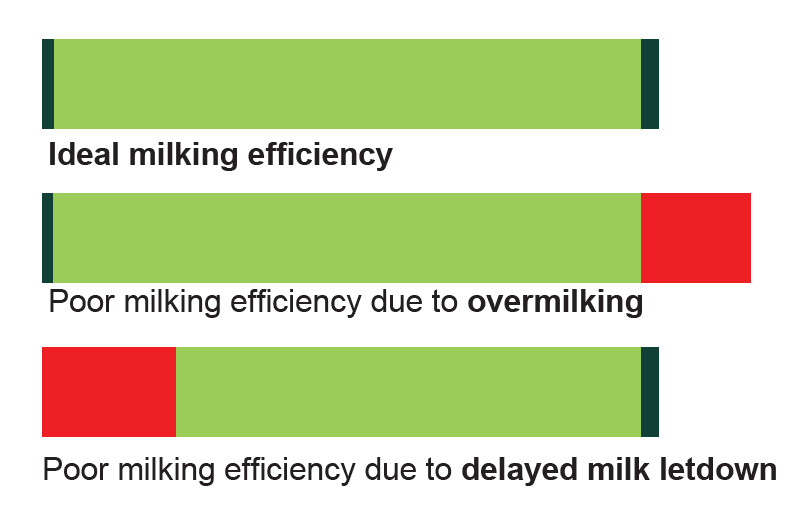

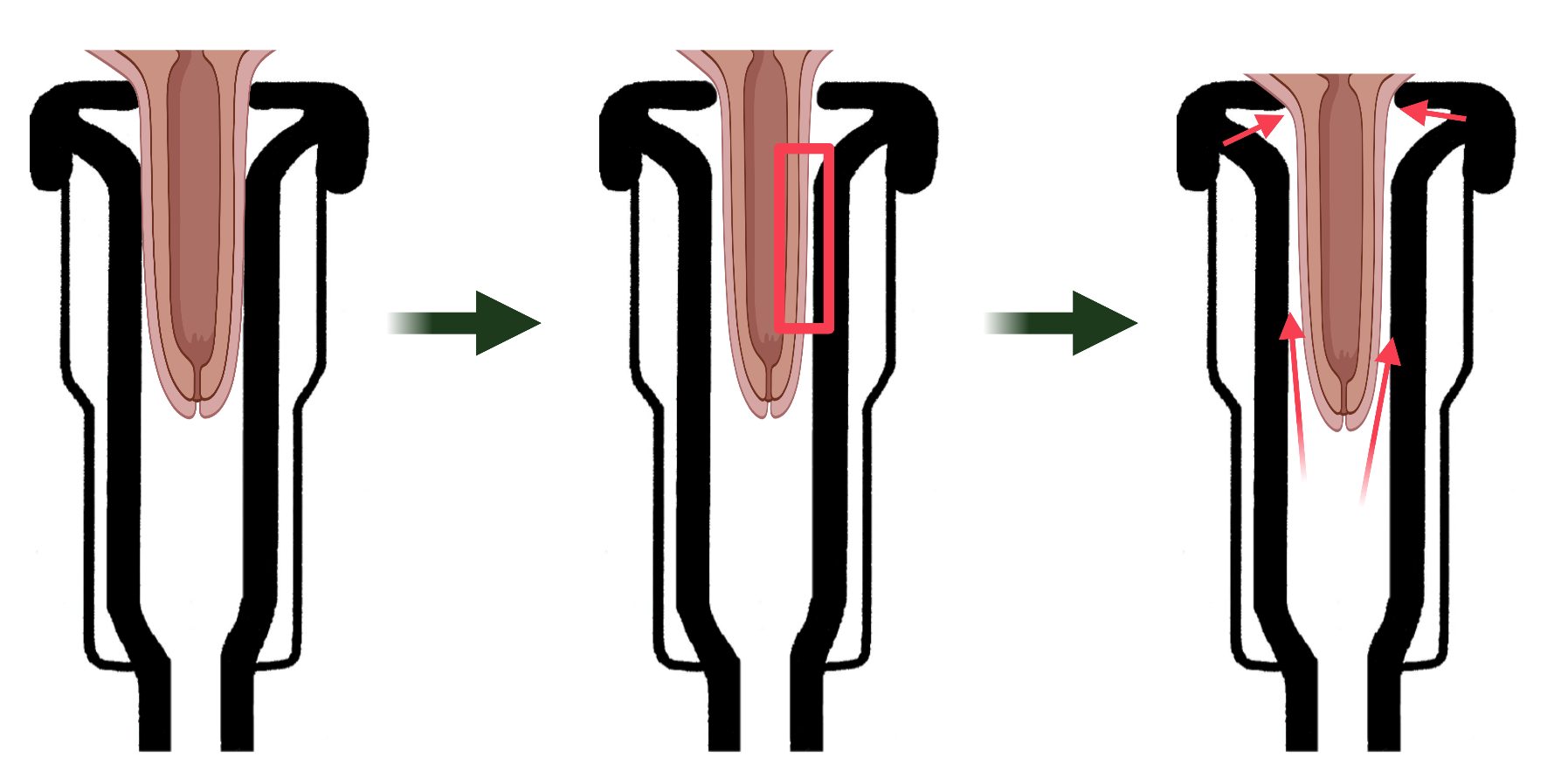

Milking efficiency is the percent of time that milk flows near maximum while a unit (cluster) is attached to a cow. For example, if a milking unit is attached for 5 minutes, and milk flows for 4 minutes and 45 seconds, her milking efficiency is 95% (285/300 seconds). When milk isn’t flowing while the unit is attached, it creates high vacuum on the teats, which disrupts blood flow, and may decrease milk quality and milk yield. There are two basic causes for poor milking efficiency: 1) milking routines that cause delayed milk letdown—often called bimodal milk letdown, where the milk flow starts, then stops, then starts again—and, 2) overmilking (Figure 1). Both of these problems can leave cows ‘high and dry’, and expose teats to high vacuum levels, which damages the teats and disrupts milk flow.

A minute delay equals seven pounds tossed away

Teat stimulation before milking—rubbing the udder, stripping, automated brushes, or drying with towels—activates nerves in the udder to carry an “electric signal” to the pituitary gland in the brain. The pituitary then releases oxytocin into the blood and to the udder. It takes 1 to 2 minutes to reach optimal oxytocin levels, which forces muscles that surround the milk ducts to ‘squeeze’ milk to flow to the teats. The two important points about oxytocin function are 1) giving enough teat stimulation (at least 10 to 15 seconds of actual physical touching) and 2) waiting for the latency period (more commonly known as ‘lag time’), the time interval from when teats are first stimulated until the cluster is attached.

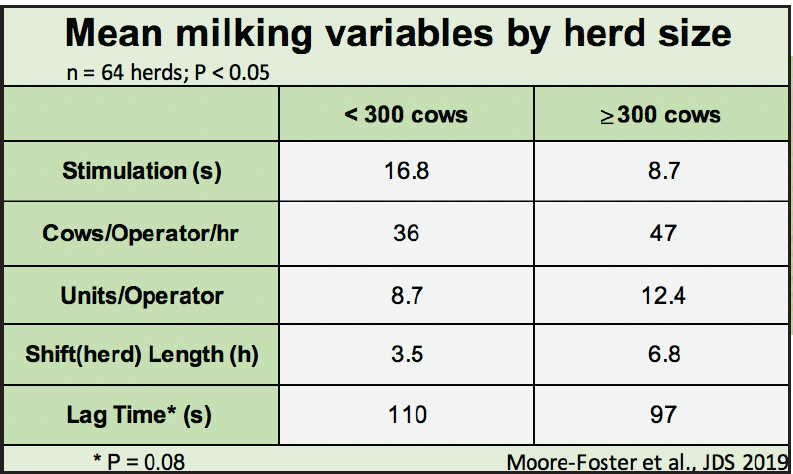

Unfortunately, many herds sacrifice adequate pre-milking preparation to enhance cow throughput in the parlor. In fact, in our study of Michigan dairy herds, we found that larger herds tended to have: 1) greater cow throughput, 2) greater workload on employees, and 3) half the stimulation time as compared to smaller herds (see table). Not surprisingly, herds with less stimulation during the milking prep are more likely to have bimodal milk letdown. On average, 25% of cows within a herd had bimodal milk let down. For one in six herds, more than half of their cows had poor milk letdown. Is this the new normal?

Why do we care if cows have a bimodal milk letdown? During bimodal letdown, teats are exposed to high levels of vacuum for approximately 45 to 60 seconds—or even longer, and it is not just the teat ends. The lack of milk flow during bimodal letdown causes the teat barrel to become thinner, which leads to a poor seal between the teat and the liner that allows high vacuum to “leak” into the mouth piece chamber, a space where there is normally low vacuum (Figure 2). High vacuum causes skin damage, blood congestion, teat swelling and shuts down the teat canal, reducing milk flow. This is painful for the cow, and she’ll respond by “dancing”, or kicking off the milking cluster. Even though the milk flow may eventually begin, cows with bimodal milk letdown have the same milking times as cows with normal milk flow. What does this mean for milk yield? If the delay in letdown is about 30 seconds to a minute, 3 pounds is lost during that milking. If the delay is over a minute, seven pounds. The longer the duration of time that it takes for milk to start flowing after cluster attachment, the more milk is lost from that milking and the more it impacts your bottom line. The more cows in the herd that have bimodal milk letdown, the more milk is lost.

What about the employees?

Ask any dairy producer or herd manager what comes to mind about milking their cows, and labor availability and protocol compliance often top the list. No one likes to be rushed, cows or employees, but as herds are getting larger, the push to get cows through the parlor seems to be on the rise. What effect does bimodal milking have on the employees? Simply, it makes their job more difficult. Trying to prep and milk cows that are kicking units off, stepping, and not wanting to come into the parlor means milkers have to spend more energy and time to complete their job. Frustrated workers often have to reattach units or place the take-off on manual to deal with the “angry” cows. Everyone knows what it’s like to milk a new heifer in the milk string. What if half of your cows act that way during milking? Also, proper teat cleaning and detection of clinical mastitis become issues in this sort of approach to udder prep. In these situations, employees can see themselves pressured to follow the milking protocol while being rushed to perform their job by the farm management, something that sometimes can be impossible to do. In addition, employees are being asked to maintain good milk quality and meet the milking schedules. All this can lead to high levels of frustration that can trigger disengagement and protocol drift, or can even push the employees to leave their jobs.

Future research at MSU

To have a better understanding of the bimodal milk letdown issue, the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine and Michigan State University Extension are working on a research project that will evaluate the impact of bimodal milk letdown on milk production in the long term. The milking records of cows from four different herds will be tracked for seven days. We will look at the milk flow records from parlor software’s and determine how many of those milking events have bimodal milk let down, and will assess if milk production is affected. On a second research project will explore how employee training can help to decrease bimodal milk let down.

So how are your cows milking? Have you watched cow behavior after cluster attachment lately? Does the flow stay consistent or does it stop a few seconds after the unit is attached? What do the teats look like when the units detach? There’s money, cow welfare and employee engagement on the line—is it worth it for you? Equipment dealers, milk quality consultants and your herd veterinarian can all be part of your milk quality team and together can optimize the milking experience for the farm, employees and most of all, the cows.

What is the balance between parlor and milking efficiency? Compared to a simple measure such as, ‘how many cows were milked through my parlor today’, the impact of bimodal letdown seems vague. Historically, we believed bimodal letdown was undesirable because it increased the unit on time, or the risk of mastitis. Bimodal flow may reduce milk quality and teat health, but the impact on a herd is difficult to measure. Thus, like subclinical mastitis that is often overlooked compared to clinical mastitis, the impact of poor milking efficiency is often overlooked compared to parlor efficiency.

Adapted from an article recently published on Hoard’s Dairyman

Print

Print Email

Email