Impact of soil blocks on yield and earliness of six tomato varieties

Soil blocking can decrease plastic use, but does it live up to the promise of higher yields and sooner harvest?

With increased interest in sustainable farming practices, there are many on-farm practices that can be considered. One practice is soil blocking, maybe most well-known for being discussed in Elliot Coleman’s “The New Organic Grower.” Soil blocking is a method of sizing up transplants in molded blocks of soil as opposed to plastic pots. The practice is said to reduce root circling, leading to increased yield, earlier harvest and more resilient plants. The practice also cuts back on the amount of on-farm plastic.

Our goal in this trial was to see if starting plants in soil blocks increased yield or decreased the time to harvest. To test this, six commercially available indeterminate tomato varieties were potted into either in a traditional pot or in a soil block at Tollgate Farm and Extension Center in Novi, Michigan. Pots were 2.75 inches long by 2.75 inches wide by 2 inches high (11.88 inches³). Soil blocks were created using the stand up six-cell blocker from Johnny’s Seeds, which created blocks 2.375 inches long by 3 inches wide by 2 inches high in dimension (14.26 inches³). The blocks have a larger volume but because wet soil is pressed into the blocks, the weight of dry soil in each treatment was comparable (41g in block, 35g pot).

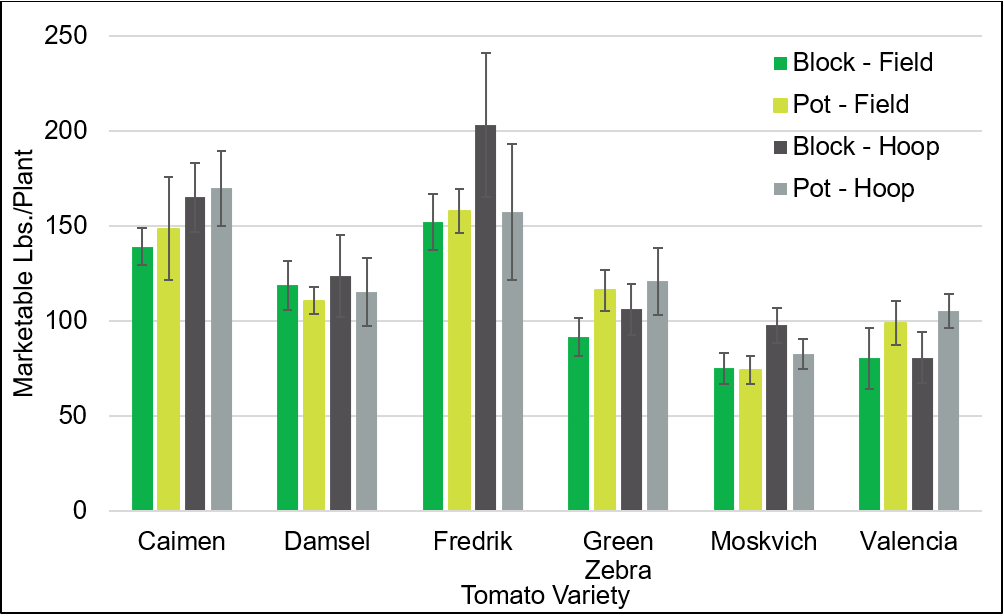

These transplants were then planted in a hoophouse or in the field. Yield was tracked through the growing season. In our trial, the methodology used to start the transplant had little effect, with variety being the most important factor in yield. For full details about the materials, methods and statistics, see the full report in the 2018 Midwest Vegetable Variety Trial Report Bulletin.

While differences were present among varieties, there were no differences between the hoophouse or field setting for per-plant yield of tomatoes started in traditional pots and tomatoes started in soil blocks (α=0.05).

The amount of time it took to prepare pots and blocks was similar, though preparing soil blocks has more nuance and is more physically demanding. It can take trial and error to find a soil mixture that will hold its shape when blocked, and adding the right amount of water to get the soil mixture malleable but not overly wet can add time to the blocking process.

There was a difference in plant height at the time of transplanting. Tomatoes grown in soil blocks were taller than those grown in pots (39.7 inches versus 27.8 inches, LSD.05=1.97). No significant root circling was noted in either treatment.

|

Table 1. Average marketable and cracked fruit yield (in pounds per plant across season) and average days to first harvest across six tomato varieties started in either soil blocks or plastic pots in Novi, Michigan. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment |

Hoop |

Field |

||||

|

Marketable Yield |

Cracked Fruit Yield |

Days to Harvest |

Marketable Yield |

Cracked Fruit Yield |

Days to Harvest |

|

|

Block |

8.09 |

0.30 |

111.1 |

6.84 |

0.17 |

98.9 |

|

Pot |

7.82 |

0.30 |

112.8 |

7.36 |

0.11 |

99.9 |

|

Grand Average |

7.96 |

0.30 |

111.9 |

7.10 |

0.14 |

99.4 |

|

LSD 0.05 |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

In the hoophouse, the per plant yield of tomatoes started in soil blocks versus pots was similar. There was also no significant difference in the yield of cracked tomatoes produced. The main differences present were between varieties. The number of days it took to reach the first harvest was comparable between the two treatments (Table 1).

In the field, the per plant yield of tomatoes started in soil blocks versus pots was not significantly different. There was no difference in the yield of cracked tomatoes between treatments. The number of days to the first harvest was also similar between the treatments (Table 1).

Overall varietal differences

The main differences present in our trial were between our six varieties. In the hoophouse, Frederick and Caiman yielded significantly higher than the other four varieties on a per plant basis. Damsel produced significantly more cracked fruit than the other cultivars. Green Zebra took significantly longer to be ready to harvest than the other varieties.

In the field, Frederik and Caiman again yielded significantly higher on a per plant basis than the other varieties in the trial. Damsel produced more cracked fruit than the other varieties. Time to harvest was comparable among all varieties in the field.

Conclusions

Soil blocks did not increase yield or decrease days to harvest in either the hoophouse or the field. In our study, the time taken to prepare transplants in both traditional pots and in blocks was comparable, but may take longer if a grower is still working out the right soil mix and amount of water to use during block formation. For grower’s with goals of sustainability, the reduced plastic of this system may be appealing, and soil blocks should not decrease production.

The trial highlights that the genetics will have one of the biggest impacts in both earliness and yield. In this trial, the highest yielding varieties in both the field and hoophouse were Caiman and Fredrik. This emphasizes the importance of on-farm research and extension variety trials. For evaluations of different tomatoes in the Midwest done by university extension educators, check out the archives of the Midwest Variety Trial Report Bulletins.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Michigan State University Extension AABI GREEEN programming grant and in-kind contributions from Tollgate Farm and Education Center. Garrett Owen and Ben Phillips helped in experimental design. Darby Anderson, the field manager, as well farm apprentices Julia Michael and Sara Elbohy were instrumental in planting, maintaining and harvesting.

Print

Print Email

Email