Industrial hemp on ballot with marijuana in November

Focus on risks of marijuana legalization could distract voters from the hemp provision and stifle opportunity for Michigan farmers.

By now, most Michiganders have heard about Proposal 1 (Prop1), the Michigan Regulation and Taxation of Marihuana Act, which will be on the ballot come Nov. 6. The main focus of Prop1 is legalization of recreational marijuana for persons 21 years of age or older, implementation of commercial production and distribution rules, and also levying of a tax on marijuana sales. Few people realize that passage of Prop1 would also legalize the cultivation, processing, distribution and sale of industrial hemp in Michigan.

Prop1 defines industrial hemp as “a plant of the genus cannabis and any part of that plant, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration that does not exceed 0.3 percent on a dry-weight basis…regardless of moisture content.” In other words, the only difference between marijuana and industrial hemp is their concentration of THC, the primary psychoactive substance in marijuana. Ingesting industrial hemp products will not get you “high,” thus eliminating any risk of abuse.

Despite U.S. farmers’ lack of familiarity with industrial hemp today, this crop is nothing new. It has been cultivated for at least 6,000 years in Asia for fiber and food. It was especially well known to history’s mariners whose sails were commonly made of canvas, a material once derived from, and named after, cannabis. The puritans brought hemp to New England as a source of fiber. It is also often noted that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew hemp for use in papermaking.

Legal cultivation of industrial hemp in the U.S. was first eroded by its association with marijuana and the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which effectively outlawed sales of all cannabis through aggressive taxation. The federal government did authorize cultivation of approximately 400,000 acres of hemp in the U.S. during the period of 1942-1945 when other sources of natural fiber were threatened by WWII. Yet, by 1957, hemp was swept from America’s agricultural landscape by increasing regulation, and synthetic fibers became the standard in many industries.

Michigan’s Prop1 is an example of the recent uptick in state and federal legislation aimed at legalizing industrial hemp. The 2014 Farm Bill included conservative language in Sec. 7606 opening the door for regulated research on the ancient crop. Soon after, Michigan’s Governor Rick Snyder signed Public Acts 547 and 548 of 2014, removing “industrial hemp” from the state’s legal definition of marijuana and authorizing industrial hemp research by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) and Michigan universities. At least 39 other states have passed similar legislation since 2014, and a number of them—Indiana, Kentucky and Colorado among others—are actively pursuing industrial hemp research today.

Unfortunately, industrial hemp research has never gotten off the ground in Michigan, which could put our farmers at a severe disadvantage if and when commercial hemp cultivation is made legal. As congress debates the 2018 Farm Bill, it seems that day may not be far off. The Senate version includes the Hemp Farming Act of 2018 (S. 2667) co-sponsored by a bipartisan coalition of more than two-dozen senators. This legislation would fully legalize industrial hemp at the federal level, opening the floodgates for new investment and a potential American hemp boom.

Canadian agriculture went through a similar process of industrial hemp deregulation beginning in 1994 with public research. Commercial cultivation was first authorized there in 1998. Today, Canadian production of industrial hemp has grown to nearly 90,000 acres. The U.S. could likely duplicate Canada’s success, but not without some growing pains. Agriculture and industry became unfamiliar with hemp production and its potential uses during prohibition, meaning that significant redevelopment will be required at all levels of the value chain to support this potential industry.

Growers north of the border and U.S. researchers have also learned that, although hemp is commonly known as a fiber crop, hemp seed and CBD are currently more valuable than the fiber. This is partially due to growing demand for hemp seed oil, which is touted for the nutritional value of its balanced omega fatty acid profile. Hemp seed and oil are incorporated in trendy health food, neutraceuticals and cosmetics.

CBD (cannabidiol) is one of a group of compounds produced by cannabis known as cannabinoids. Cannabinoids are also naturally produced in the human body and are thought to influence coordination and movement, pain, emotions and other functions. CBD from industrial hemp has a growing reputation as medicine used to treat pain, inflammation, epilepsy and a range of other conditions. While less valuable than seed or CBD, the fibrous stems of industrial hemp can still be used to create a wide range of industrial products from paper to insulation and even car parts. An industrial hemp crop harvested for seed and fiber can be competitive with traditional field crops, producing average net returns of $200-$400 per acre.

It is interesting that the future of industrial hemp in Michigan will once again be tied to marijuana under Prop1. This association, withstanding the change in Michigan’s legal definition of industrial hemp, has caused organizations that are generally pro-hemp to come out against Prop1, including Michigan Farm Bureau. What’s more challenging is the fact that voters may never realize Prop1 is a referendum on industrial hemp because the official ballot language doesn’t even include the word “hemp.”

To be clear, Michigan State University and MSU Extension are not for or against Prop1. Section 57 of the Michigan Campaign Finance Act prohibits a public body like MSU or an individual acting for a public body like MSU from using public resources to assist, oppose or influence the nomination or election of a candidate for public office or the qualification, passage or defeat of a ballot question.

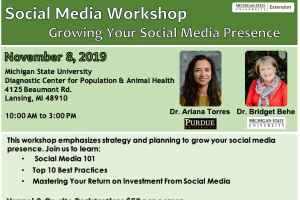

Our job at MSU Extension is education, and hopefully reading this article will help you and other voters make an informed decision on Nov. 6. For more information on the potential risks and benefits of recreational marijuana under Prop1, check out the Prop1 summary or upcoming Ballot Proposal Forums available through MSU Extension.

Print

Print Email

Email