Investigating Influenza: Preventing Spread of IAV-S at Swine Shows

Swine influenza, otherwise known as IAV-S (Influenza A virus-swine) or H1N1, has been a growing concern over the past several years and for good reason.

Swine influenza, otherwise known as IAV-S (Influenza A virus-swine) or H1N1, has been a growing concern over the past several years and for good reason. The CDC estimates that 61 million people were infected with H1N1 in 2009 alone and as many as 575,000 people have died from H1N1 worldwide since its initial appearance in 2009. What makes this virus so infectious, and how can it’s spread be limited?

What even is a virus? Viruses are disease-causing agents that use the host’s own cellular machinery to replicate and spread within the body and to the world beyond. Viruses generally damage host cells when they exit infected cells, leading to the symptoms seen or felt during viral infections.

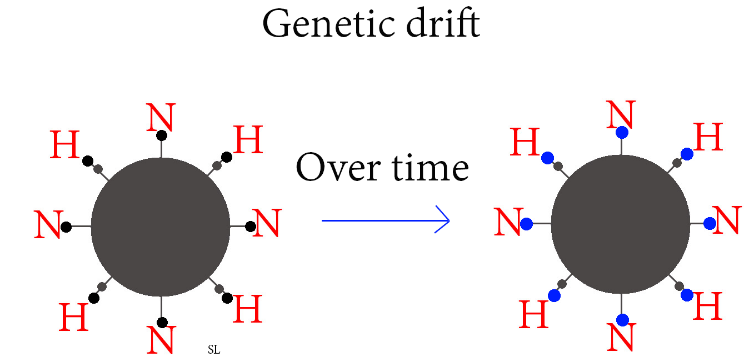

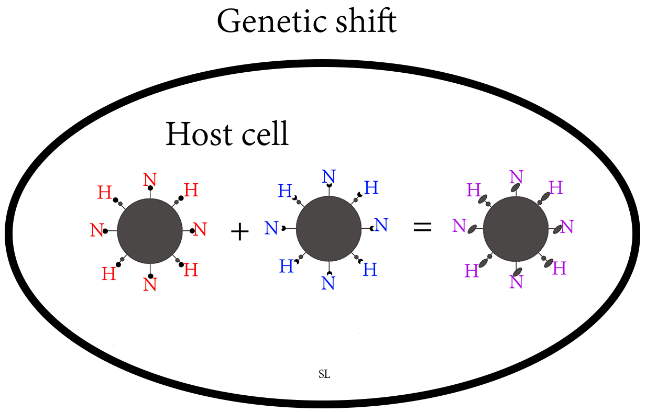

You may notice that each year the influenza vaccine is different. This is because there are multiple strains of influenza and new strains are frequently formed. New strains result from changes to the genetic information of influenza viruses, and these changes occur through two primary mechanisms, genetic drift and shift. Genetic drift refers to very small changes in the genetic makeup of a virus that lead to limited alterations in the appearance of influenza virus. When a virus undergoes genetic shift, however, large changes are made to the DNA sequence of a virus and results in considerable alterations in the appearance of a virus.

Genetic shift leads to formation of viruses that can cause considerable harm to humans and animals due to rearrangement of two viral surface structures, referred to as hemagglutinin and neuraminidase (aka H and N). These pegs allow influenza viruses to attach to host cells and are what white blood cells, the bodies defense, recognize when an individual becomes infected with a form of influenza they have met previously. However, influenza can become unrecognizable to white blood cells when it rearranges its H and N through genetic shift, leading to disease and possibly even death in susceptible individuals.

What does it take for two unique influenza viruses to meet up undergo genetic shift. Proximity. Case in point - youth swine shows provide excellent opportunities for H1N1 and possibly other strains of influenza to be transmitted to people from swine or vice versa. Influenza, in general, is spread through two primary mechanisms. The first mechanism being transmission through aerosolized droplets that are released when pigs or people breath, cough, etc, and the second being when people or pigs come into contact with nasal secretions from either species.

Many individuals attending or participating in swine exhibitions are unaware that they are putting themselves and others at risk. A large Michigan swine show took place recently. The show was very well assembled with many outwardly healthy hogs participating. However, a large number of the exhibitors could be seen eating and drinking in the hog pens or very near (<10 feet away) hog pens. Not only that, but there were multiple areas set up along or in the alleyways where people were cooking food in crockpots or had large trays of food. This may not seem problematic to the average individual, but these were high traffic areas which were visited by multiple people that had been handling hogs, increasing the possibility of these locations serving as reservoirs for H1N1 and other diseases.

The following diagram shows 10 of the behaviors or actions which can lead to increased spread of influenza (and other diseases) between people and pigs at shows. It should be noted that all of the listed observations were seen at the show mentioned above.

Figure 3. Behaviors and observations which promote spread of influenza between humans and swine. 1: Shavings on the ground from pigs and people moving in and out of pens. 2: Slow cookers. 3: Containers with cut fruit. 4: Bags of chips, pretzels, and other easy to grab snack items that can be eaten as people move to and from pens. 5: Boxes of donuts, muffins, or pastries. 6: Bottles of pop or water being consumed by exhibitors while in pig pens. 7. Individuals carrying buckets in and out of pens would occasionally stop and grab a food item on their way to or from pens. 8. Coolers of food or beverages. 9. Consumption of finger foods in alleyways. 10. Pigs moving up and down alleyways next to people consuming food/beverages.

Figure 3. Behaviors and observations which promote spread of influenza between humans and swine. 1: Shavings on the ground from pigs and people moving in and out of pens. 2: Slow cookers. 3: Containers with cut fruit. 4: Bags of chips, pretzels, and other easy to grab snack items that can be eaten as people move to and from pens. 5: Boxes of donuts, muffins, or pastries. 6: Bottles of pop or water being consumed by exhibitors while in pig pens. 7. Individuals carrying buckets in and out of pens would occasionally stop and grab a food item on their way to or from pens. 8. Coolers of food or beverages. 9. Consumption of finger foods in alleyways. 10. Pigs moving up and down alleyways next to people consuming food/beverages.

Some aspects of influenza cannot be controlled or prevented against, such as genetic alterations leading to new influenza viruses. However, there are measures that can be taken to limit the spread of influenza and help prevent formation of previously unseen influenza strains. Don’t attend swine shows if you think you might be sick with influenza. Don’t eat or drink near swine and be sure to wash your hands before and after interacting with pigs and before consuming food or beverages. These steps may be simple and easily overlooked but are vital in limiting the spread of the disease which has infected millions.

References:

"Updated CDC Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States, April 2009 – April 10, 2010" https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/pdf/CDC_2009_H1N1_Est_PDF_May_4_10_fulltext.pdf

Bliss N, Nelson SW, Nolting JM, Bowman AS. Prevalence of Influenza A Virus in Exhibition Swine during Arrival at Agricultural Fairs. Zoonoses Public Health. 2016 Sep;63(6):477-85. doi: 10.1111/zph.12252. Epub 2016 Jan 11. PubMed PMID: 26750204.

Bouvier, Nicole M.; Palese, Peter (September 2008). "The Biology of influenza viruses" Vaccine. 26 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): D49–53. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.039

Killian ML, Swenson SL, Vincent AL, Landgraf JG, Shu B, Lindstrom S, Xu X, Klimov A, Zhang Y, Bowman AS. Simultaneous infection of pigs and people with triple-reassortant swine influenza virus H1N1 at a U.S. county fair. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013 May;60(3):196-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01508.x. Epub 2012 Jul 9. PubMed PMID: 22776714.

Print

Print Email

Email