EAST LANSING, Mich. — Five Michigan State University researchers have received a $750,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) to study crop uptake of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and how to prevent it.

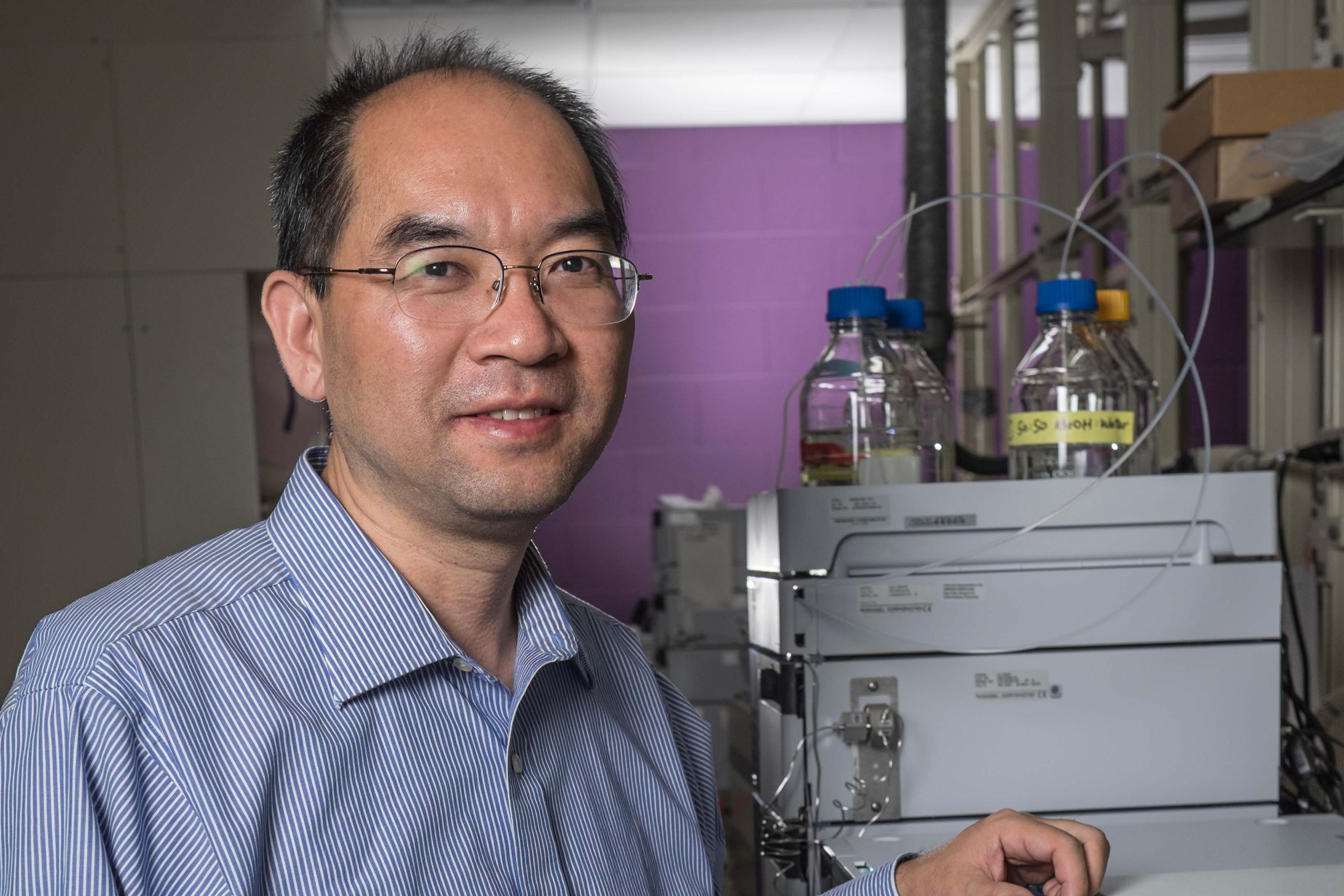

The project is led by Hui Li, a professor in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences (PSM) who specializes in soil chemistry and the environmental occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants. The four co-principal investigators are from PSM as well.

- Stephen Boyd – a University Distinguished Professor and expert on remediation of contaminated soils.

- Ray Hammerschmidt – a professor who studies plant physiology and disease resistance.

- Kurt Steinke – an associate professor and MSU Extension specialist in soil fertility and nutrient management.

- Wei Zhang – an associate professor of environmental and soil physics who looks at the transport processes of contaminants in soil, water and plant systems.

PFAS contamination has made headlines around the country, and there is mounting concern about the effects these chemicals have on public health. In response, MSU has invested in the Center for PFAS Research and has developed several multi-institutional, nationwide partnerships to address the problem. Research is looking to quantify the exposure risk to humans and the environment, develop possible remediation strategies, and explore PFAS alternatives for industries that have relied on them.

For the newly funded project, Li and his team are evaluating novel ways to immobilize PFAS in soils to prevent plants from coming in contact with them. Since the group believes soil pore water is the primary carrier by which the chemicals move to the plant root zone, they hypothesize that soil amendments could prevent plants from taking in PFAS.

“We believe the primary vehicles used by PFAS to enter agricultural lands are contaminated irrigation water or land-applied biosolids, which is used in the agriculture community to improve soil health and provide nutrients,” Li said. “But there is increasing evidence that they inadvertently introduce harmful chemicals to soil, water and plants.

“It’s extremely difficult to stop PFAS from entering the environment entirely, but we’re working to uncover methods that make the chemicals less bioavailable to plants for uptake.”

The team will perform lab, greenhouse and field experiments to quantify PFAS in soils irrigated with PFAS-contaminated water. Then, they will test two sorbent materials — layered double hydroxides and modified biochars — and their ability to take in PFAS. Researchers will assess potential PFAS leaching from these materials.

They will seek to validate the findings by comparing test plots of carrots, corn and wheat using soil amendments to control plots without amendments.

“This research will ideally identify field-scale approaches to preventing PFAS from entering crops,” Li said. “It’s important that any strategies we design are efficient and implementable on agricultural operations of all sizes.”

Li’s efforts with PFAS began with seed funding from Project GREEEN (Generating Research and Extension to meet Economic and Environmental Needs), a partnership among MSU, Michigan plant agriculture organizations and the state of Michigan.

The goal of the Project GREEEN work was to evaluate the uptake and accumulation of PFAS in food crops from soils amended with biosolids. Researchers developed ways to analyze PFAS in plants, while publishing a comprehensive review paper that updated current knowledge on plant uptake of PFAS and identified information gaps.

“I’m very pleased that Project GREEEN assisted these researchers in obtaining federal research funding to address this important issue,” said Jim Kells, Project GREEEN coordinator. “This is a great example of the intended outcome from Project GREEEN grants.”

The seed funding also led to another recently funded PFAS project from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Li is examining current biosolid treatment processes for PFAS concentration and leachability, and will attempt to bridge knowledge gaps in the fate, transportation, occurrence and plant uptake of PFAS. The data will help researchers create models that quantify exposure risk to humans.

“This is a significant public health concern that requires our immediate attention, and there are a lot of knowledge gaps in both basic and applied research,” Li said. “Our team is thankful to USDA, EPA and our many other partners for their support.”

Print

Print Email

Email