Scenario-based shoreline planning can help improve coastal management

Using simple, decision-centered, scenario-based planning has helped some Michigan Communities navigate the uncertain and complex task of shoreline planning.

Many Michigan communities have been managing the impacts from 2020s record setting Great Lakes water levels. Communities along shorelines are faced with difficult conversations about how to plan for and manage development along their coasts in a way that balances the changing reality of the Great Lakes with their own community priorities and goals. Simplified, decision-centered, scenario-based planning can be a tool for local governments to grapple with those complexities as they craft their master plans and hazard mitigation plans.

Planning can be challenging

Coastal planning and hazard mitigation in Michigan falls largely to local units of government through their planning and zoning authority. However, research has shown that local units often face a number of challenges when planning for hazard mitigation. Among those is the perception that hazard mitigation work is highly technical and requires specialized experts. Coastal land use decision makers also face the dual uncertainty of changing lake levels and increasing storm intensity. Taking a decision-centered scenario planning approach has helped some communities with that challenge.

The American Planning Association describes scenario planning broadly as “a process to support decision-making that helps urban and rural planners navigate the uncertainty of the future in the short and long term.” According to the US Army Corps of Engineers scenario planning has been used for over 50 years by diverse organizations to develop strategic plans in the face of great uncertainty. Given the changing water levels and increasing storm intensity of the Great Lakes, developing both short- and long-term plans along Michigan’s coast could be informed by the scenario planning process.

Scenario planning has a reputation for being technical and complex though and often beyond the reach of local communities. Urban planning experts saw the potential for simplifying the process and focusing on the factors communities did have control over. Researchers, led by Richard Norton at the University of Michigan, worked with shoreline communities to develop the process. Then, in partnership with the City of Grand Haven and Grand Haven Charter Township, the scenario-based planning approach was tested as they both went through master plan updates.

Identifying scenarios

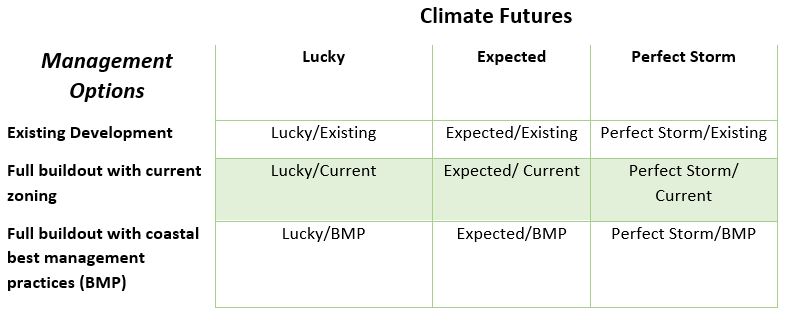

So how does the process work? The researchers started by identifying the future potential scenarios that communities would need for coastal planning. These nine scenarios were developed by considering three possible climate futures (taking into account lake levels and storminess) and three possible management options. Those scenarios are summarized in Table 1.

Those nine scenarios are a combination of factors outside of the community’s control (climate futures) and within their control (management options). Focusing on a limited number of scenarios kept the analysis manageable. Each of the nine were then analyzed using readily available data to determine the impact to land and structures that could be expected for each. A version of this process can be seen in action in these slides from a presentation made to Southwest Michigan communities.

Once the impacts under each scenario were estimated, the communities incorporated that data into their public participation and broader master plan process. Presenting the scenarios in this way created a space for residents to discuss the unpredictability of the future and the risks posed to the community.

Using information in planning

At the end of this process both communities included information from the process in their Master Plan updates. The City of Grand Haven incorporated all analyses, findings, and conclusions for coastal management from the process into their master plan. Grand Haven Charter Township chose to include conceptual overviews and policy recommendations in the master plan (with additional materials in appendices).

As communities (both coastal and inland) continue to face growing impacts from climate change, scenario planning may be a powerful tool for conceptualizing and discussing complex potential future situations. Those discussions can then inform the planning and future development of a community in a way that reflects how the community wants to respond to a changing climate. Using a simple, decision-centered, scenario-based planning process can help communities gain some of the benefits of scenario planning in an accessible way.

More resources available

To learn more about coastal planning in Michigan and access resources please visit EGLE’s Coastal Management page. Here you can find a series of six videos produced in 2020 in partnership with Michigan Sea Grant and Michigan State University Extension on Building Coastal Resilience, among many other great resources for coastal planners and communities. More resources can be found on the Resilient Michigan Coastal Resilience Toolbox. MSU Extension also has a team of Land Use Educators around that state to provide education and training on planning and zoning.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This article was prepared by Extension educator Tyler Augst, in part under Michigan Sea Grant award NA180AR4170102 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statement, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email