Today’s Great Lakes commercial fishing and fish processing industries look to future

Sea Grant survey reveals need for place-based job training opportunities that include cultural and regulatory contexts specific to the region.

On the salty coasts of the U.S., commercial fishers and seafood processors have many opportunities for workforce development and training. However, in the Great Lakes region where state and tribal fishing licenses are actively fished, there are currently no such programs offered. That is about to change. Michigan Sea Grant and Wisconsin Sea Grant are partnering on a project funded by the National Sea Grant Office to develop a framework for a commercial fisheries and fish processing training program. This joint project has placed the industry and partners in a position to capitalize on Young Fishermen’s Development Act funding. Congress has authorized $2M in funding per year beginning in 2022 for the act.

The joint project has highlighted that differences in gear and regulations across the Great Lakes among state licenses and tribal licenses creates a need for place-based training opportunities that include cultural and regulatory contexts specific to the region.

As part of the project, the team conducted an exploratory analysis, a regional online survey, and semi-structured focus groups. The team is currently drafting a framework using these results to propose a stakeholder- and rightsholder-driven apprenticeship program. The team anticipates using this framework to work collaboratively with commercial fishers and seafood processors in the Great Lakes region in order to mentor the next generation of the industry’s workforce using structured, cross-discipline training curricula. Here is a summary of the survey results:

Great Lakes regional survey

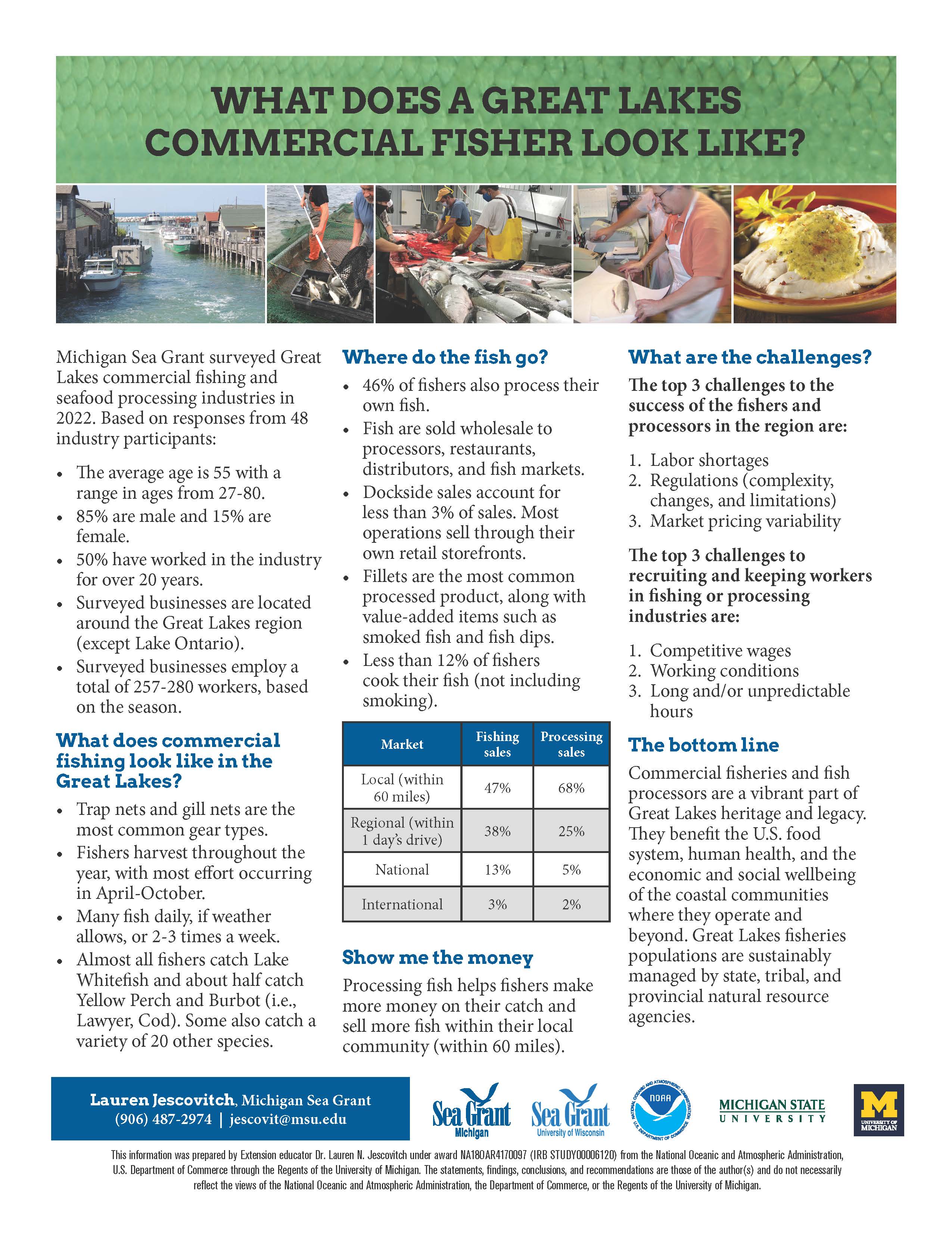

A survey was distributed to the Great Lakes Sea Grant Fisheries Network and to individuals who own or work for either commercial fishing operations or seafood processors. In total, 48 responses were received representing U.S. businesses across all Great Lakes (except for Lake Ontario). These businesses employ 257-280 workers, based on the season.

Of the 48 responses, 71% fish or had fished commercially for profit (50% own their own license), 50% of respondents said they commercially process fish, and 46% of the respondents said they do both (commercially fish and process). Respondents were 85% male and 15% female with an age range of 27-80 years old with an average age of 55. Half of this workforce has worked in their job for over 20 years. These survey results highlighted the depth of legacy and how family-oriented these industries are in the Great Lakes region.

What do they catch?

The 71% of respondents who commercially fish represent over 4.7 M lbs. of fish harvested from U.S. Great Lakes waters in 2021. Many fishers can have multiple licenses, but the majority of the respondents fish on Lake

Michigan in either Wisconsin or Michigan waters. Almost all of these fishers catch Lake Whitefish and about half catch Yellow Perch and Burbot (AKA Lawyer, Freshwater Cod). Additionally, some reported harvesting a variety of 20 other species (see 2020 status of the industry). The most common gear types used are trap nets and gill nets. The fisher respondents report that they are out on the water catching fish from “ice out to ice in,” which is typically from April through October. In some regions, the fishers also harvest and process Lake Herring (Cisco) into December. Many fishers fish daily, if weather allows, or 2-3 times a week. Fish from the boat are mostly sold to (in order starting with the most common): a processor, their own fish market, restaurants, distributors, or other fish markets. Very few utilize farmers markets (<20%), institutions (cafeterias, etc; <9%), community supported agriculture (CSA; <9%), or dockside sales (boat to customer; <3%).

Where do the fish go?

One of the most interesting findings from the survey was the change in market based on who sells the fish: the fisher or the fish processor. The local market (within 60 miles) typically sells more processed fish, while more fishing sales go instead to either regional, national, or international markets. The most common processed products include filets (with de-pin boning and descaling) as well as value-added items such as smoking and fish dips. Many processors also vacuum pack and flash freeze their products. Very few processors (12%) cook their fish (not including smoking).

|

Market |

Fishing sales |

Processing sales |

|

Local (within 60 miles) |

46.5 % |

68.1 % |

|

Regional (within 1 days drive) |

37.9 % |

25.4 % |

|

National |

12.7 % |

5.1 % |

|

International |

2.9 % |

1.5 % |

Processing their own fish helps fishers make more money on their catch (greater profit margins) and they sell more fish within their local community (within 60 miles; see table above).

What are the challenges?

The survey illuminated some industry challenges.

The top 3 challenges to the success of the fishers and processors in the region were reported as: 1) labor shortages, 2) regulations (complexity, changes, and limitations), and 3) market pricing variability.

The top 3 challenges to recruiting and keeping workers in fishing or processing industries were reported as: 1) competitive wages, 2) working conditions, and 3) long and/or unpredictable hours.

Although employees for a commercial fisher or seafood processor need many specialized skills, most respondents (77%) said they are willing to teach the skills and all necessary training an employee needs on the job. Businesses look for a variety of backgrounds when hiring an employee. About half say background doesn’t matter/it’s unimportant (55%) while others have a minimum requirement of a high school diploma or GED (39%). Because most of the businesses will provide on-the-job training, they are looking for workers who are dependable, have a strong work ethic, enjoy this kind of work, and have some experience with fishing or processing. If the company is owned by a Tribe or a co-op, then passing drug tests and the long hiring process become the biggest barriers to workforce recruitment. Looking forward, about half of the businesses need help with processing fish and the rest need help with fishing and maintaining or repairing equipment.

The bottom line

The future of the Great Lakes commercial fishing industry depends on recruiting and retaining the next generation of commercial fishers and fish processors. Commercial fisheries and fish processors are a vibrant part of Great Lakes heritage and legacy. They benefit the U.S. food system, human health, and the economic and social wellbeing of the coastal communities where they operate and beyond. Great Lakes fisheries populations are sustainably managed by state, tribal, and provincial natural resource agencies.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research, and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This information was prepared by Extension educator Dr. Lauren N. Jescovitch under award NA18OAR4170097 (IRB STUDY00006120) from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email