Researcher takes worm’s view of prairie restoration

Add Summary

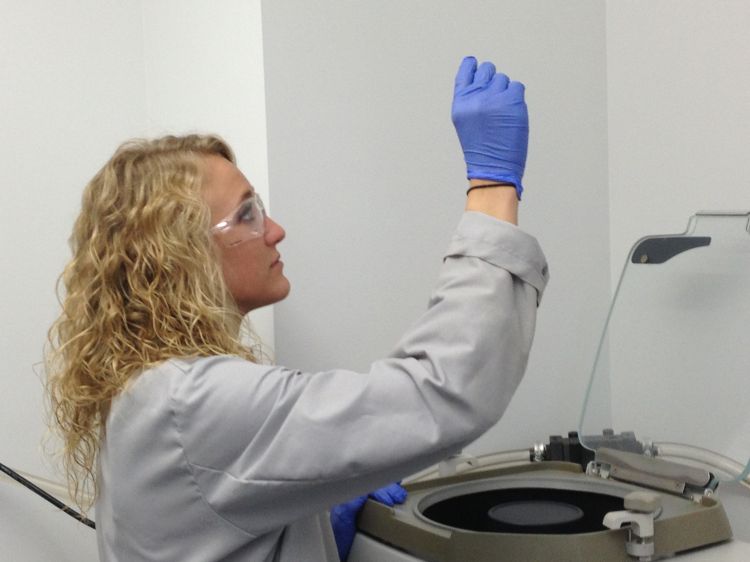

A new Michigan State PhD student began her research career digging into the world of microbes in the soil to understand what it takes to nurture a repurposed prairie back to health -- a deep topic.

The early work of MSU doctoral student Anna Herzberger, when she was an undergraduate at Eastern Illinois University and at the University of Wisconsin (UW) – Madison, probed the complex world of microbes to understand why turning cornfields back into thriving prairies was difficult. Restored prairies, it turns out, often suffer the same fate as neglected household gardens – with grasses running amok over flowers.

In recent journal publications in Restoration Ecology and PLoS One, Herzberger and her colleagues seek to understand how the microbial ecology of soil is changed by agriculture, and what may be needed to allow prairies to thrive again.

“Prairies are awesome – they can provide carbon sequestration, biodiversity, they can filter water and shelter wildlife, and they’re beautiful,” Herzberger said. “We need those benefits back, and we’re doing a poor job of restoring them.”

To get the dirt on prairie restoration, she worked on understanding how microbes affected two common prairie grasses, prairie dock and white wild indigo, which are flowering plants common in established, healthy prairies.

prairie grasses, prairie dock and white wild indigo, which are flowering plants common in established, healthy prairies.

In the Restoration Ecology paper “Plant-Microbial Interactions Change Along a Tallgrass Prairie Restoration Chronosequence,” they evaluate how different stages of restoration affect plant growth, and how the soil’s microbial make-up affects that.

It appears that the microbes in soil dedicated to crops may give grasses a big jump early in the restoration game. The grasses share enough similarities with corn that allows them to flourish early on, and overtake the other plants. The research also raised questions about whether the microbes, years down the road, serve to inhibit the grass growth.

At the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center at UW, she worked within the center’s broader goals of understanding what it takes to strike a balance between the benefits of growing crops for energy and the environmental advantages of prairies, and how the soil’s microbes affected that balance. Her role was to monitored change in the microbial community.

“We saw a quick return of microbes known to thrive in prairies, which gives us hope that a successful prairie may be well on its way,” Herzberger said.

Herzberger begins her doctoral studies at MSU’s Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (CSIS) with Jianguo "Jack" Liu, the center's director. She plans to continue to explore how agriculture lands are used, and how those uses change; but instead of taking a close-up look, she’ll be looking at agriculture from a global perspective.

Besides Hezberger, “Bouncing back: plant-associated soil microbes respond rapidly to prairie establishment” in PLoS One was written by David Duncan and Randall Jackson from Wisconsin. The Restoration Ecology paper was also written by Scott Meiners, J. Brian Towey, Paula Butts and Daniel Armstrong of Eastern Illinois University.

Print

Print Email

Email