Bulletin E3202-7

Forest Types of Michigan: Northern White-Cedar

DOWNLOAD

November 4, 2015 - MSU Forestry Extension Team

The northern white-cedar (cedar1) forest type occupies 1.3 million acres (about 6.5 percent) of Michigan’s forest area.2 Cedar stands are strongly dominated by northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis) — about 70 percent of the forest type volume is cedar. About 21 other tree species occur in the cedar forest type. The most common associates are black spruce, balsam fir, tamarack, paper birch, red maple, white pine and white spruce. Each of these species represents less than 4 percent of the volume in the forest type.

Cedar also grows in other forest types. It is an occasional associate most commonly in northern hardwood, swamp hardwood and aspen forests. About 30 percent of the statewide cedar volume grows outside the cedar forest type.

The Trees

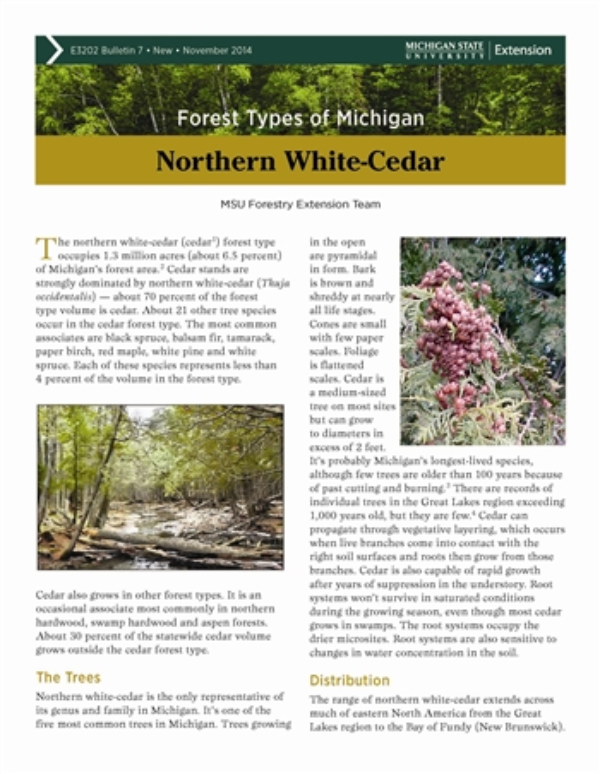

Northern white-cedar is the only representative of its genus and family in Michigan. It’s one of the five most common trees in Michigan. Trees growing in the open are pyramidal in form. Bark is brown and shreddy at nearly all life stages. Cones are small with few paper scales. Foliage is flattened scales. Cedar is a medium-sized tree on most sites but can grow to diameters in excess of 2 feet. It’s probably Michigan’s longest-lived species, although few trees are older than 100 years because of past cutting and burning.3 There are records of individual trees in the Great Lakes region exceeding 1,000 years old, but they are few.4 Cedar can propagate through vegetative layering, which occurs when live branches come into contact with the right soil surfaces and roots then grow from those branches. Cedar is also capable of rapid growth after years of suppression in the understory. Root systems won’t survive in saturated conditions during the growing season, even though most cedar grows in swamps. The root systems occupy the drier microsites. Root systems are also sensitive to changes in water concentration in the soil.

Distribution

The range of northern white-cedar extends across much of eastern North America from the Great Lakes region to the Bay of Fundy (New Brunswick). It is common throughout the northern two-thirds of Michigan. Nearly 80 percent of the cedar forest type area lies in the Upper Peninsula, and most of that is in the eastern U.P.

Ecology

The cedar forest varies from a rich association of many species, including rare species, to nearly pure stands of cedar with a largely barren understory. Most cedar types occur on wetland sites, although some of the best growth occurs on limestone escarpments along the northern shore of Lake Michigan. In places, cedar can be found on upland sites, sometimes invading old fields. Cedar is a prolific seeder in three out of five years. Seeds disperse in the fall and into the winter. Seeds need raised microsites (hummocks) with rotting stumps and large logs to germinate. Leaf litter and thick moss inhibit germination. Fire is uncommon on most cedar sites, but when it does occur, excellent seed beds may result.

On good sites, cedar growth can be fairly rapid; on most sites, growth is limited by soil and moisture conditions.

Overbrowsing by white-tailed deer has prevented cedar seedlings from reaching sapling stage across most of northern Michigan for many decades. Most cedar stands have distinct browse lines in areas of high deer densities.

Management and Silviculture

The overriding factor in cedar management is the population levels of white-tailed deer. If deer pressure is low, site conditions and regeneration status will help determine choices between even-aged or uneven-aged silviculture. Eligible management systems range from clearcutting (including patch- and strip-cutting), shelterwood harvests and selection silviculture.5 Landowners are well-advised to engage a consulting forester to assess conditions for a particular stand. Tops of harvested trees and thick brush may be retained to deter browsing of regenerating cedar. Sites with thick moss may need partial scarification, but landowners need to be cautious to avoid flattening the microtopography (natural unevenness of the ground).

Thinning will improve light conditions in overstocked stands, but too much thinning can create an environment for undesirable competition by fir, spruce and other indigenous species and certain invasive species, such as buckthorn. In thinning, remove smaller and suppressed stems first, and then manage for stand density. Cedar stands generally should carry higher densities than most Michigan forest types. Desired stand densities range from 90 to 150 square feet per acre, depending on stand age, average tree diameter and site conditions.

Landowners should avoid altering hydrology by building permanent roads and trails. Roads can serve as dams, raising water levels and flooding cedar stands. Conversely, ditching or similar activities can dry out cedar stands, resulting in cedar mortality and failed regeneration.

Tree Health Issues

Northern white-cedar has few serious insect and disease threats, although the exotic Japanese cedar long-horned beetle may cause significant damage should it arrive in Michigan. Young cedar and the forest type are very vulnerable to browsing by white-tailed deer. Heavy browsing pressure has prevented cedar establishment in many stands for decades. Snowshoe hares can damage or kill young cedar, too. Stripped bark in late winter or early spring may be caused by red squirrels collecting nest material.

Wildlife Habitat

Cedar foliage is a favorite winter food for whitetailed deer, though deer will not eat cedar during the summer, when other foods are plentiful. In the Upper Peninsula, at the northern range of deer habitat, the cover that cedar provides is a more important habitat feature. In dense cedar stands, winter temperatures are higher, wind speeds are substantially reduced, and snow is shallower than in hardwood stands. A deer will lose less energy by eating nothing under a cedar stand than foraging for food in deep snow and cold temperatures. Deer will seek out these stands for the thermal cover, not so much for the availability of browse. A wide range of other species take advantage of cedar in winter. Seed crops are favorite foods of many small birds, mice and voles. Dense stands provide good cover for animals that nest in trees. Elongated, deep cavities created by pileated woodpeckers serve as nesting places for many other species.

Landowner Tips

|

See http://michigansaf.org for forest management guidelines from the Michigan Society of American Foresters.

1 Northern white-cedar is not a true cedar. “Arbor vitae” is the common horticultural name for this species and others in the genus Thuja. “Arbor vitae” is Latin for “tree of life.” Early French explorers reportedly drank a tea made with cedar foliage to prevent scurvy.

2 Acreages and volumes of species and forest types are derived from the USDA Forest Service forest inventory and analysis data at www.fia.fs.fed.us/tools-data.

3 Heitzman, E., K.S. Pregitzer and R.O. Miller. 1997. Origin and early development of northern white-cedar stands in northern Michigan. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 27(12): 1953-1961, 10.1139/x97-157.

4 Hofmeyer, P.V., L.S. Kenefic and R.S. Seymour. 2007. Northern White-Cedar (Thuja occidentalis, L.): An Annotated Bibliography. [where published]: Cooperative Forestry Research Unit, University of Maine.

5 Boulfroy, E., et al. 2012. Silvicultural Guide for Northern White-cedar. Gen. Tech. Report NRC-98. [where published]: USDA Forest Service and Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service. Available at www.nrs. fs.fed.us/pubs/gtr/gtr_nrs98.pdf.

Print

Print Email

Email