Alien language: The importance of metaphor

Part 4: Metaphors help simplify and explain complex research, but they can cause errors in reasoning, lead to misunderstandings, and even reinforce stereotypes that undermine the goals of inclusive science.

The team behind the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS) spends a lot of time thinking about language use as we maintain our database. This “Alien Language” Extension article is part of a series highlighting the importance of deliberate language use in invasion biology, from defining what exactly “invasive” means (Part 1) to why it’s important to clarify the difference between “nonindigenous” and “invasive” species (Part 3), to why calling a nonindigenous species “established” in a particular area (Part 2) can cause trouble for funding and management strategies.

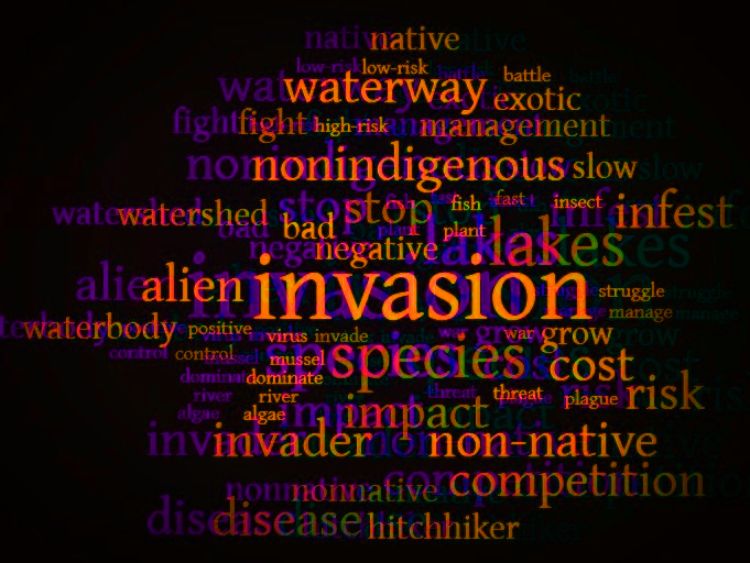

Talking about invasive species can be a complicated task. Whether introducing students to the concept of Great Lakes invaders for the first time or discussing effective outreach strategies with environmental managers, word choice matters. In addition to technical terms, metaphors and illustrative language are a major part of effective science communication. As it turns out, the figurative language we use to talk about invasive species can actually be just as important as the technical jargon.

Why are metaphors so important in science communication? First, metaphors are a key part of how scientists talk about and conduct their research. Researchers use analogies to develop hypotheses and interpret the results of their experiments, and then use metaphors to communicate their findings. Even the most fundamental scientific concepts -- the cell (named after the rooms of medieval monks), the food “chain,” or “agents” of infectious disease -- are ultimately based in figurative language. However, figurative language is – to use another metaphor – a double-edged sword. When used well, metaphors help simplify and explain complex research or issues to the public, but when used carelessly, they can cause errors in reasoning, lead to public misunderstandings, and even inadvertently reinforce stereotypes and messages that undermine the goals of inclusive science.

Military and nativist language

Two very common metaphorical frameworks used in invasion biology utilize military and nativist language, respectively, to call researchers and the public to action. Military metaphors are among the most common in invasion biology -- in fact, “invasion” itself is a military term. From references to “the war on invasive carp” to calling for “support for our troops” (in this case, the spread of invasive species), it’s easy to see how deeply military language is embedded in invasion biology. War metaphors have strong emotional appeal to many stakeholders and can help generate political support for funding species management and control efforts as well.

There are a number of problems with leaning too heavily on military metaphors when talking about invasive species. War metaphors are based on the idea of “good versus evil” and “us versus them” -- concepts that break down rapidly when applied to invasive species. For as destructive, unsightly, and inconvenient as invasive organisms can be, they aren’t deliberately malicious. These species simply do what they can to survive in a new habitat, even when it harms native species and changes ecosystem dynamics. Framing conflict with invasive species in terms of war can erase the reality that human behavior is largely responsible for this conflict in the first place: changing patterns of global trade and travel have been the source of biological invasions for centuries.

Nativism is another common rhetorical framework that positions nonindigenous species as inherently threatening to native ones by virtue of being “foreign” and is meant to stir up instincts to protect our home from destructive outsiders. This framework attracts attention and generates discussion when it’s used in science communication, but it’s not necessarily positive at all. Unfortunately, nativist metaphors can come across as xenophobic at best, or even outright discriminatory. There’s a long, ugly history of conflating human immigrants with biological invasions, and many environmental organizations are now advocating for renaming certain species to avoid replicating stigma, such as the initiative to switch from the term “Asian carp” to “invasive carp.”

Towards alternative metaphors

Military and nativist metaphors remain widely used because they’re effective at generating discussion and engagement, but they’re far from the only useful frameworks for talking about biological invasions.

Writing by indigenous scholars and other keepers of traditional ecological knowledge presents some very different rhetorical frameworks for talking about invasive species. The team behind the Great Lakes-based Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu uses the deliberately neutral term “non-local beings” rather than “invaders” to describe species that aren’t originally from North America. This concept of non-local beings disentangles a species’ origin from its behavior in the environment: just because a species is non-local in these frameworks doesn’t imply that it is necessarily harmful. Recent papers on the rhetoric of invasion biology suggest that a health-based framework might be a useful alternative model for conceptualizing the ecological impacts of invasive species too. Thinking about invasive species as an injury to the resilience of an ecosystem, an infection needing medical care, or even a chronic health condition that may never be “cured” but that can still be managed for better quality of life are all rich metaphorical frameworks that science communicators can continue to build from and explore.

At the end of the day, the more metaphors we have in our communication toolkit, the better we can tailor our messages to different audiences. Maybe we don’t always have to frame our work in terms of waging war or fighting foreigners – instead, thoughtfully examining common metaphors and developing new ones can help give science communicators, researchers, and stakeholders more nuanced ways to talk about nonindigenous species.

To see applied examples of how some of these metaphors can play out in a Great Lakes-specific context, our colleagues at Wisconsin Sea Grant have been looking into the use of military, nativist, and other metaphors as communication frameworks for developing public engagement around zebra mussels, and shared their research and experience in this Lake Talk. The Wisconsin Sea Grant podcast “Introduced” also has a number of episodes that discuss language use in invasion biology, and are well worth listening to.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This article was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA180AR4170102 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email