Before settling for a public hearing, consider the continuum of public involvement

Referring to the continuum of public involvement before the next big community decision will help your local government design the most effective method for engaging the public.

Our form of government is commonly called a democracy, but a more accurate term would be a representative democracy. According to John J. Patrick’s book “Understanding Democracy: A Hip Pocket Guide” published by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, a representative democracy is a democratic form that is characterized by elected representatives acting in formal institutions and processes for the people of the district from which they were elected. Some, such as John Keane, Professor of Politics at the University of Sydney and at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin, have argued that since the middle of the last century, democracy has been shifting into a form that is better termed a monitory democracy. A monitory democracy involves a broader set of interests and processes, beyond elected representatives, that work to monitor and exert influence over those in positions of power. Ways that this can be seen in a monitory democracy include citizen juries, appointed commissions, special committees, focus groups, summits and the like. Such groups may exist outside the formal institution of the state, but inform and influence the actions of the representative democracy.

Further evidence of a shift beyond a strict representative democracy is the growing number of citizens that are seeking more direct ways to be involved in decision-making. With such motivation, “Citizens are arguing for a new notion of governance that requires political leadership to engage with citizenry in ways that allow for ongoing input into decision-making and policy formation,” explained Kumi Naidoo at the World Bank Presidential Fellows Lecture. The growth of youth advisory councils among local units of government like Saline and Holland here in Michigan are further evidence of the desire for input in decision making beyond the strict representative democracy. Survey research from University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State and Urban Policy has also shown increasing trust among local officials for citizens to be responsible participants in the decision making process and increasing support among local officials who believe citizens should recommend specific decisions.

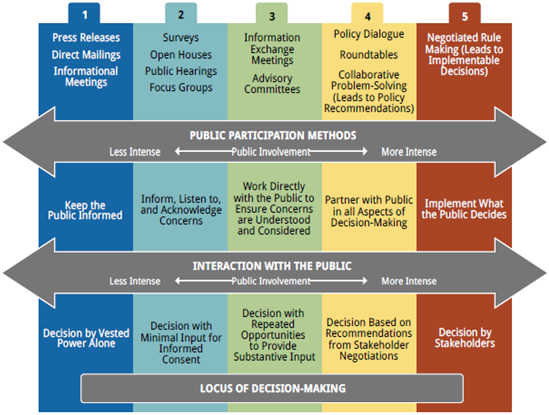

Recognizing this new democratic reality, how should a governmental unit involve the public in various decisions and policy formulations? Figure 1 depicts a framework for considering such a question, the Continuum of Public Involvement from a North Carolina Cooperative Extension watershed planning guide. The Continuum of Public Involvement presents five approaches to public involvement (seen across the middle row) that intensify in interaction as you go from left to right. Below each approach, the locus of decision making is listed. Above each approach are some example methods for that approach. Each of the public involvement approaches are considered in more detail below.

- Keeping the public informed

Sometimes it is perfectly appropriate for a governmental unit to maintain full control of a decision and simply inform the public of the issue, the decision and the outcome. For instance, an employment-related concern between the elected body and its chief administrative official would be the kind of issue that would typically be handled internally, with the public being informed. Although the flow of communication is one-way, the result should be an informed and educated public. A press release or an informational meeting can accomplish this goal. - Informing and listening

Other times the governmental unit may wish to inform public opinion on a particular issue and then collect feedback on how to handle that issue. Let’s say, for example, a major public infrastructure investment is needed (e.g., a new fire station). The local government may wish to educate the public as to why the infrastructure is needed, how much it will cost and how the improvement will benefit the community. The decision-making body then may wish to gather design ideas or comments on various siting considerations. The decision is still that of the governmental unit, but the public’s input is highly valuable for arriving at a decision that has the broadest support by the community. The public hearing, which is required for many local government decisions, is an example method for this level of public involvement. - Incorporating public concerns and interests

To have a true dialogue with the public, involvement methods that allow for two-way communication are needed. Open houses, public meetings, and advisory committees (assuming the public is adequately represented) allow for information exchange whereby the governmental unit responds to the public’s comments and reengages the public in still more conversation and deliberation. The intent is to create a process and environment that provides multiple opportunities to inform, listen, and refine decisions or plans. The final decision remains in the hands of the governmental unit. With heightened interest in being involved in decisions, the public seems to be demanding this level of public involvement as the new minimum for many community decisions. - Partnering with the public

Policy development at the local level that involves diverse interests or groups requires still greater intensity of public involvement. Issues that involve many diverse interests, are broad in complexity (or geography), are controversial or costly require greater intensity of public involvement. Partnering with the public means that the decision-making authority is no longer exclusively in the hands of the governmental unit. Instead, decisions are made by consensus in which the governmental unit actively works with the public towards a shared vision, policy or decision. Facilitated processes to raise concerns, share ideas, minimize conflicting views and bring diverse interests into greater alignment are typical of the methods within this type of public involvement. - Implementing what the public decides

The ultimate way to involve the public in decision making is for the public to make the decisions. Like with the last type of public involvement described, facilitation techniques on the part of the governmental unit or a third party are fundamental to the process. The difference between partnering with the public and implementing what the public decides is that, with the latter, the governmental unit is not at the table. Instead, when implementing what the public decides, the governmental unit is only enabling the public dialogue or decision-making process to take place and committing to endorsing, authorizing or implementing whatever it is the public ultimately decides. A charrette is an example of a public involvement method that takes the intensity of public participation to the level at which decisions are made by the stakeholders themselves.

In addition to varying levels of public participation, there are also varying levels of time and cost associated with the public involvement continuum. While these are legitimate factors to consider when selecting a public participation method, governmental units should recognize the added value that results from effectively involving the public in terms of improved communication, increased awareness, broader understanding and heightened trust.

More information on effective public participation is available through the National Charette Institute, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation’s Six-Step Guide to Public Participation, the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), or search for additional resources in the Community Development Extension Library. Copies of the “Local Watershed Planning: Citizen Participation Guidebook” are available upon request from the North Carolina Water Resource Research Institute by contacting Christy Perrin (christy_perrin@ncsu.edu).

Print

Print Email

Email