From chillin’ to chilly – Natural ventilation during the winter months for dairy barns

Michigan regularly sees days well below freezing. Farmers can use natural ventilation basics for dairy barns using these suggestions for ventilation practices and preparation for winter weather.

Ah, summertime in the barn. Curtains wide open, a breeze coming through the barn and fans kicking on to cool the cows. Alas, seasons change, and barn ventilation strategies must change with it. Knowing how and when to shift your ventilation system over for winter weather conditions will help protect your milk yield and cow health.

What is ventilation?

Ventilation is a system that provides fresh air while removing stale, tainted air. For dairy farms, the intended goal with this movement of air is to remove moisture, dust and noxious gases while also removing heat during the summer months.

How do we bring fresh air into the barn?

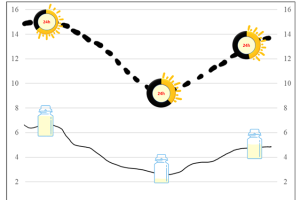

Naturally ventilated barns rely on wind and natural air buoyancy for air changes. Mechanically ventilated barns, which include cross-ventilated, tunnel and hybrid barns, utilize fans to achieve the optimal number of air changes per hour (ACH). During the winter months, the recommendation is to have between four to eight ACH. As a point of reference, during the summer months, barns should have 40 to 60 ACH.

How does air move through a naturally ventilated barn?

Warm air rises, cool air sinks. Warm air will rise through the open ridge while cool air enters through the eaves and open sidewalls. Potential ways to achieve gentle air movement throughout the colder months includes using high volume, low-speed (HVLS) fans, variable speed fans, inlet location or baffle placement. It is important to research which methods are optimal for your specific situation.

During severe cold or winter storm conditions, the freestall barn sidewall should be open one-half inch of the ridge opening, for example a 90-foot-wide building would equate to a 9-inch sidewall opening. Once weather conditions are less severe, sidewalls can have larger openings, with the goal of maintaining temperatures within 10 degrees of outside temperatures. It is strongly suggested to not completely close eave inlets during cold weather to prevent creating a humid barn environment.

Dairy Cattle Body Heat Regulation

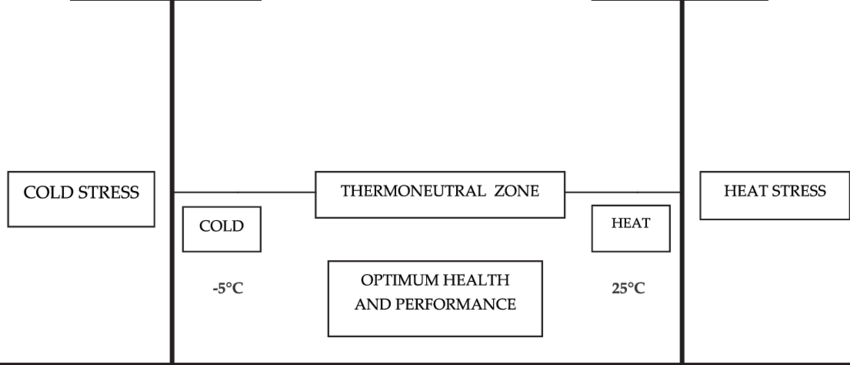

Rick McBay, a natural ventilation specialist with Faromor, states that cows will start to eat for the replacement of body heat when air temperatures are below 23 degrees Fahrenheit/negative 5 degrees Centigrade. This means that cows will need more feed to maintain body heat during these weather conditions. On average, a cow produces around 14,400 watts of excess heat, equivalent to the output of a small electric heater. The Mechanical Ventilation Systems for Livestock Handling technical booklet explains that heat loss depends primarily on the environment.

Sensible heat loss is a measure used to explain how much heat an animal can lose based on environmental temperature. Sensible heat loss occurs in temperatures below a cow’s thermoneutral zone below 41 F. The colder the air, the greater amount of heat being pulled away from the cow. To compensate for this, cows will increase their total feed intake to maintain bodyweight.

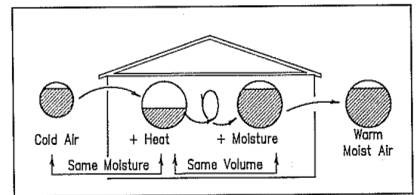

The primary objective of ventilation in winter months is to remove moisture, along with noxious gases and dust. This directly reduces the risk of pneumonia in cattle. Moisture in the barns occurs mainly by respiration from the cows. When cold, dry air is brought into the barn, the air is warmed by animals and equipment. As a result, this air can now hold greater levels of moisture. While air is moved through the barn moisture is captured along with the noxious gases and dust and then exhausted out of the building.

Dr. Kevin Janni, a professor and extension engineer at University of Minnesota, has written numerous articles on the topic of ventilation. He shared that throughout the winter months, maintaining clean and dry stalls is critical for cows to maintain their body heat. A wet stall will take heat away from the cow through conduction. Susan Gay noted that a 1,300-pound cow produces around 30 pounds of water vapor per day. This makes keeping a barn warm without the formation of condensation a difficult task. Closing a barn may be a necessity when preparing for extreme weather events. Here are some hazards to keep in mind for when barns are closed for an extended period:

- Creating a humid environment

- Increasing the risk of respiratory disease

- Humidity deteriorates wooden structures more quickly

- Exposure to high levels of noxious fumes is a health and safety concern for employees and cows.

- Condensation will form on housing structure, potentially compromising structural integrity or risk of ice buildup. This can create a hazard for employees and cows.

“When you walk into the barn, you should smell feed before you smell manure,” McBay said. “If you smell manure first, it means that the ammonia level is too high. This in turn means the humidity level is too high and your ventilation rate is too low … letting fresh air in can easily resolve this.”

Michigan State University Extension recommends the following steps to address winter ventilation:

- Test your current air flow. Look for areas with stale air as these will be your high problem areas for moisture control. Your ventilation equipment dealer may provide this service.

- Unroll all curtains, checking for holes, and patching holes when present.

- Ensure all curtain mechanisms are working properly and complete repairs prior to colder weather conditions.

- Assess all electric components, drive units, and gearboxes for automated systems

- Check for gaps between curtains, doors, and other openings. Seal them to minimize drafts.

- Assess, clean, & repair fans that may be utilized during winter months, such as HVLS fans or variable speed fans.

- If using paneling, inspect the panels for any damages and repair accordingly.

- Inspect, clean, and repair ridge spaces, clearing them of bird nests or other blockages.

- Encourage your staff to make note of areas in the barn that may not be getting adequate ventilation, drafts, and ice buildup on walkways and buildings.

Controlling the internal barn environment during winter weather can be a tricky thing. With thorough preparation and an understanding of the main goals of ventilation, managing the barn temperatures and moisture can be done, even in extreme winter weather.

For additional information or if you are interested in discussing or evaluating your barn ventilation, please contact the Michigan State University Extension Dairy Team personnel.

Print

Print Email

Email