Mystery of the Great Lakes buffalo

Not all buffalo roam the plains. Large rivers and productive lakes are the habitat of an entirely different kind of buffalo. Bigmouth buffalo, smallmouth buffalo, and black buffalo are rare in the Great Lakes region, their origins remain somewhat obscure.

No matter how much time you spend on Michigan’s lakes and rivers, surprises still await. This past spring, I was casting a tiny stickbait on four-pound test line from my kayak in a flooded backwater off the Grand River, when just such a surprise made me drop my jaw.

My lure hit the water, dove under with the turn of the handle, and stopped in its tracks. I set the hook with a flick of the wrist, but instead of the feisty tug of a white bass or  diving pull of a slab crappie, the sight of a three-foot long blue behemoth launching into the air twenty feet from the tip of my rod greeted me.

diving pull of a slab crappie, the sight of a three-foot long blue behemoth launching into the air twenty feet from the tip of my rod greeted me.

It was one of those rare moments that do not seem real because they are so unexpected. The fish was wider around than my seven-year old daughter and its color would have seemed more fitting on a coral reef than beneath the muddy floodwaters. In a fraction of a second, it was gone. Perhaps a hook had merely nicked its fin, or perhaps the feeble hookset was not enough to bury a barb in its lip.

No matter, it is always the one that gets away that sparks the most curiosity. Besides, I had some idea of the species of this fish. I had come across some like it more than a decade before, on east side of the state. It was a buffalo — not a bison — but the scaly variety.

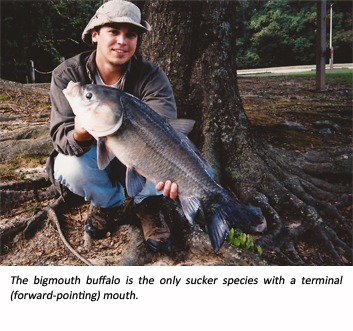

Even though they are roughly the same size and shape as non-native common carp, buffalo are not closely related to carp. The carp is a member of the minnow family, while buffaloes are members of the sucker family. The bigmouth buffalo, smallmouth buffalo, and black buffalo are all native to the Mississippi River basin. Things get a bit more complicated in the Great Lakes, though.

Stocking records from 1918 through the early 1920s indicate that buffalo were intentionally stocked in U.S. waters of the Lake Erie basin (buffalo are a popular food fish and the target of commercial fishers in southern rivers). Unfortunately, the old records did not list the species stocked, and the fact that they were stocked does not necessarily mean they were not native to the basin.

This was intriguing – had I hooked into a rare species at the northern edge of its range or a fish that was intentionally introduced to the Great Lakes? In Lake Erie, commercial fisheries for bigmouth buffalo took off a few years after the 1920s stockings. A few hybrids of bigmouth and smallmouth buffalo also showed up in the mix. This suggests that bigmouth buffalo had been rare or absent prior to stocking, and that a handful of smallmouth buffalo may have been mixed in with bigmouth buffalo that were stocked in larger numbers. Just across the lake, neither species showed up in Canadian waters until bigmouth buffalo were recorded in 1957.

In the Lake Michigan basin, museum records of black buffalo date back at least as far as 1929, when a specimen was collected from Black Lake (now Lake Macatawa). There are no early records that clearly indicate buffalo were stocked in west Michigan rivers, but it is interesting that the black buffalo does not seem to be native to lakes Erie and Huron. Black buffalo were not found in Saginaw Bay until 1958 or in Lake Erie until 1978, and it seems unlikely that they would go unnoticed for so long in such heavily fished areas if they were native.

To make matters more confusing, the three buffalo species regularly hybridize and produce fertile offspring. This is particularly likely when populations are small and breeding partners scarce. A recent study of buffalo genetics found all three in Ontario waters of Lake Erie and Lake Huron. The study concluded that although physical traits were distinct enough to maintain the classification of the three as distinct species, there was also a great deal of introgression (movement of genes from one species to another due to hybridization and backcrossing).

So there you have it. The big one that got away might have been a black buffalo, a hybrid, an introduced species, or a rare native fish. Either way, it was a great reminder that mysteries still lurk in the depths of muddy rivers and between the lines written in countless stacks of library books, museum records and online databases.

Print

Print Email

Email