Sandhill crane crop damage program offered April 18 in Escanaba

Learn about managing sandhill cranes, participate in Avipel crane repellent on-farm demonstration and receive free product and resources.

The return of migrating birds to Michigan signals spring is here, a welcome sight for most of us. Sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) are perhaps the most iconic of these seasonal visitors. Their rattling bugle calls seem to breathe life back into the thawing landscape and spread a sense of hope for the season to come. However, there is a subset of the population that may not fully share this sentiment: corn growers who experience crop damage caused by sandhill cranes.

Sandhill cranes are lanky but graceful birds; a rusty gray color with spindly legs, a long, slender neck and striking red crown. They are thought to be among the oldest bird species living today, existing for some 10 million years in their current form. The eastern population of greater sandhill cranes migrates from the southeast U.S. to breeding territory that stretches across Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Ontario. The birds arrive in southern Michigan beginning in early March each year, reaching northern locations in Michigan a few weeks later.

“Cranes are kind of unique in the sense that they often return to the same site that they were the previous year,” said Tim Wilson with USDA Wildlife Services. “Often, they will nest around field edges or the edges of wetlands.”

Sandhill cranes are a classic conservation success story. Extirpated from much of the Midwest by the late 1800s, the plight of sandhill cranes inspired Aldo Leopold’s Marshland Elegy in 1937. However, conservation efforts have reversed that trend, allowing crane numbers to rebound since the 1970s.

“Wetland protections, implementation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918), and adaptation of sandhill cranes to agricultural systems has allowed this population to increase dramatically in the Midwest. They are doing very well,” said Andy Gossens with the International Crane Foundation. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service management plan for sandhill cranes includes an original population goal of 30,000 birds for the eastern population. It is estimated that the eastern population of sandhill cranes includes over 80,000 birds today, nearly three times the target population, with at least 20,000 cranes spending their summers in Michigan.

Damage from sandhill cranes and prevention

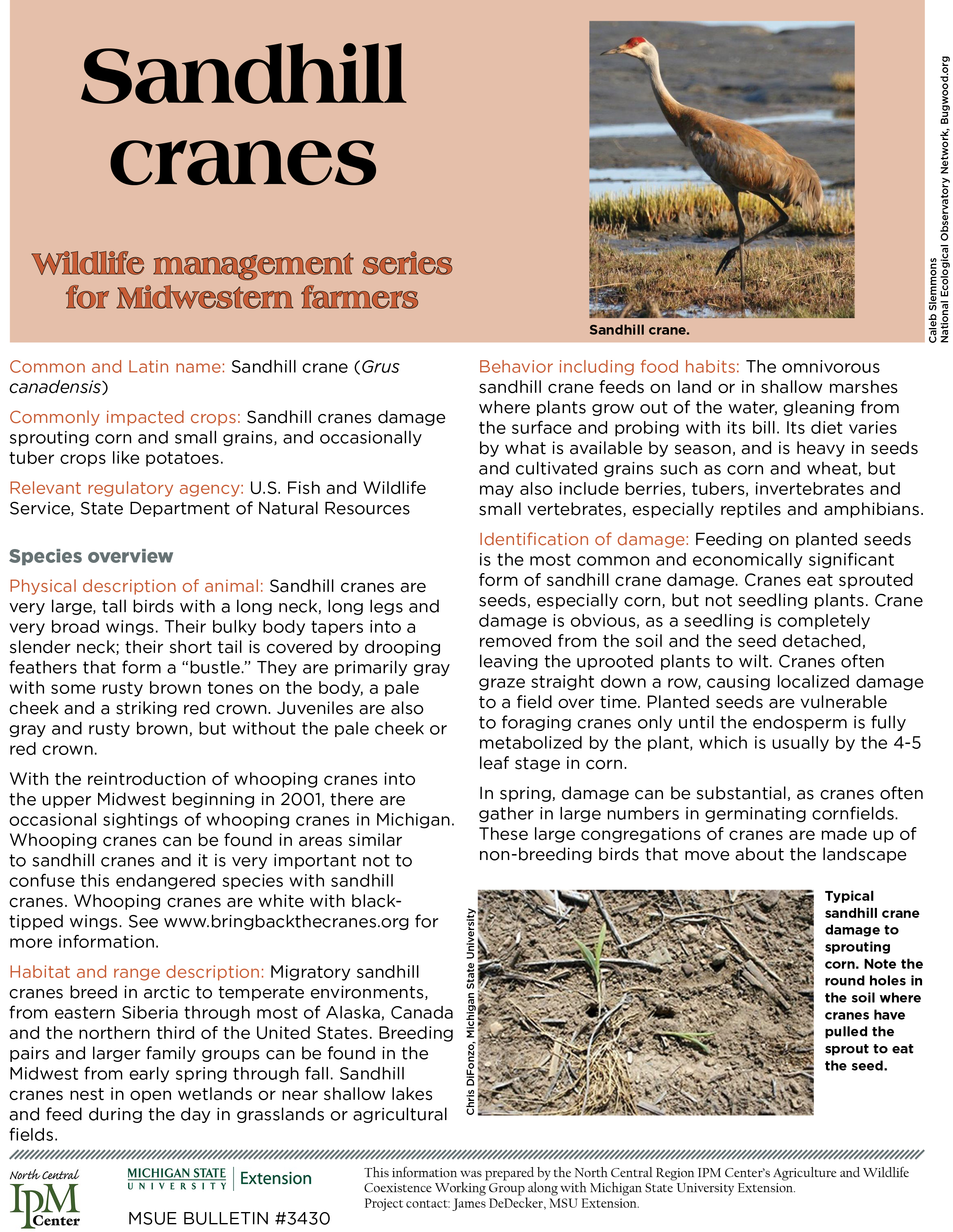

As the population of sandhill cranes continues to expand throughout the Great Lakes region, conflicts between agriculture and cranes are on the rise as well. Agricultural damage from sandhill cranes most often takes the form of birds feeding on sprouting corn or wheat seed. When feeding in a corn field, they use their beak to pull out entire seedlings and then consume the seed that is still attached to the young plant. Cranes will feed on corn seeds throughout the seedling stage until the endosperm that was present in the seed is completely metabolized by the plant.

Damage can be quite extensive, as cranes usually pluck sections of row throughout the field, creating large gaps in stands. This reduces yield potential directly, and also causes problems for the plants that remain by opening up space for weeds.

There are few methods available for reducing sandhill crane damage in Michigan corn fields. Deploying scare tactics like noise makers or predator effigies and consistent harassment may work to some extent.

“Instill in them a fear of humans. This is the time of year to be doing that, as they are returning to those fields,” said Wilson. “It’s something that is going to have be done on a regular basis. Just going out there once or twice and seeing the birds fly away isn’t going to solve the problem.”

Lethal removal can help to reinforce scare tactics. However, due to federal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, depredation permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service must be obtained before implementing lethal control of sandhill cranes. Around 1,000 cranes are killed annually under depredation permits in Michigan, mostly in the southwest Lower and eastern Upper Peninsulas. Both scare tactics and lethal control are time consuming, as they require persistently monitoring a field. These methods may also move cranes to neighboring fields, and thus spread rather than reduce damage.

Some have called for a crane hunting season in Michigan, but experts suggest fall hunting would do little to directly address crop damage, which occurs primarily in spring. States that have implemented crane hunting offer only a few hundred permits with individual bag limits in the single digits. This is because sandhill cranes are somewhat vulnerable to population decline, having to reach four to seven years of age to reproduce and only fledging one to two offspring per breeding pair each year. Striking a balance with this species through hunting could be difficult, not to mention they are beloved by many avian enthusiasts.

“A sandhill crane hunting season would (also) increase the risk of accidental shooting of endangered whooping cranes. Since the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership established the Eastern Migratory Population of Whooping Cranes in 2001, over 10 whooping crane shootings have occurred in the population, accounting for over 20 percent of the population’s mortality,” reads an online statement from the International Crane Foundation.

Using Avipel to control sandhill cranes

Another method of controlling crane damage that is gaining popularity is the use of Avipel (anthraquinone), a non-lethal and non-toxic repellent seed treatment. Sandhill cranes that ingest Avipel treated seeds experience immediate, but harmless, digestive repellency and will learn to avoid eating treated seeds.

“This is a learned response,” said Dan Propst with Arkion Life Sciences, the maker of Avipel. “The birds are going to have to get out there and sample the seed. Depending on how many birds you have, you could see a little more, or less damage. The more birds you have, the more sampling that is going to take place.” Still, research has proven this to be an effective method for reducing crane damage. “If they try a few kernels, they are going to stop and move on to other things,” Propst noted. He explained that cranes may still be present in treated fields, but they will instead feed on insects or amphibians.

Avipel comes in both dry and liquid formulations, is compatible with existing seed treatments and can be purchased from most agricultural input suppliers. Prior to this year, Avipel has been used in Michigan under a Section 24(c) exemption. This year however, Avipel’s liquid formulation received approval from the EPA for a new federal label, expanding registration to all 50 states for use in field corn and sweet corn. The dry product is still available under the 24(c) exemption. Typically, the farmer’s cost of applying Avipel is $6-10 per acre.

April 18 GUPAA annual meeting and free resources

For more information on sandhill crane ecology and damage management, attend the Growing U.P. Agriculture Association’s (GUPAA) annual meeting and educational program on April 18, 2019, from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. at Bay College in Escanaba, Michigan. Participants will hear presentations from GUPAA, the International Crane Foundation, USDA Wildlife Services and Arkion Life Sciences, the maker of Avipel repellent.

For more information on sandhill crane ecology and damage management, attend the Growing U.P. Agriculture Association’s (GUPAA) annual meeting and educational program on April 18, 2019, from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. at Bay College in Escanaba, Michigan. Participants will hear presentations from GUPAA, the International Crane Foundation, USDA Wildlife Services and Arkion Life Sciences, the maker of Avipel repellent.

Corn growers in attendance will also be invited to participate in an Avipel demonstration project organized by Arkion LS and Michigan State University Extension, receiving a free sample of Avipel and application advice. For more information or to register, call the Upper Peninsula Research and Extension Center at 906-439-5114.

In a complimentary effort to assist farmers in the Midwestern U.S. with addressing wildlife damage management on the farm, the Great Lakes Ag and Wildlife Coexistence Working Group has developed an initial series of wildlife damage management fact sheets that address eight wildlife species commonly impacting farmers, including white-tailed deer, sandhill cranes, black bears, coyotes, crows, song birds, voles and wild turkeys. These fact sheets address damage identification, species behavior, current mitigation recommendations and contact information for relevant regulatory agencies. The fact sheets are available for free download at MSU's Wildlife Management page and will also be available at the April 18 program.

The International Crane Foundation has also recently published an extensive review of this topic called “Cranes and Agriculture: A Global Guide for Sharing the Landscape,” which available for free download.

Print

Print Email

Email