When it comes to carrots: Want not, root-knot

Northern root-knot nematodes can often achieve high population densities on root vegetables without expressing of any above-ground symptoms.

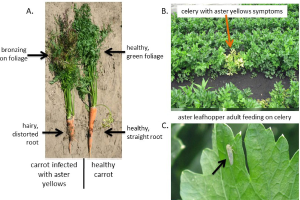

I met a grower this fall who mentioned his carrots were looking pretty ragged this year. He was right. The foliage was short and every carrot we pulled was hairy, lumpy and fingering out every which-way like a sprangle-rooting sugarbeet in compacted soil. However, this soil had good tilth, and carrots like these had not been observed. It was determined he had a severe northern root-knot nematode infestation.

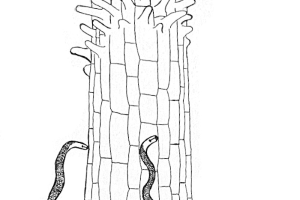

At this point in time, northern root-knot nematodes are the only major species of root-knot nematodes that overwinter in Michigan vegetable crops. As a plant parasite, they rely on root tissue to feed on. Females can lay up to 1,000 eggs apiece, which can complete development within four weeks under optimal soil temperature ranges (60-75 degrees Fahrenheit). Once the eggs hatch, the juveniles actively search within a few inches for host plants by traveling along capillary water pockets in between soil particles. Through multiple generations per year, they can slowly spread throughout a crop. If left undetected, they can be moved greater distances than they can travel on their own through freeloading on soil clinging to farm equipment.

Though all root vegetables can host northern root-knot nematodes, carrots are particularly sensitive to them. However, celery, lettuce, onions and parsnips can suffer significant yield losses due to northern root-knot nematodes. Some root veggies, like rutabagas, radishes and beets, may withstand a light infestation, but will actually be maintaining the nematode population above threshold level of one to 10 second stage juveniles per 100 cubic centimeters of soil for carrot crops. Then, when a carrot rotation comes along they get severely nailed.

Currently, there are not many post-plant management options to clean up infestations completely. Therefore, most management actions must take place prior to planting. One method to reduce populations is to plant non-host grass crops, like corn, wheat, barley, oats or sorghum, along with cover crops like sudangrass, tall fescue or rye. It is estimated for every year you plant a non-host crop, the population density of northern root-knot nematodes is reduced 50-90 percent. However, that is not always an option and there are both fumigant and non-fumigant nematicides, some of which can be used prior to, at or post-planting. Such chemicals include Vapam, Telone II and Vydate. Always follow the label!

So before you head to the tropics for the winter, monitor your root vegetable soils and prevent calamity by collecting a soil and root sample and sending it to Fred Warner at the Michigan State University Plant & Pest Diagnostics. It is strongly advised that all fields are sampled for plant-parasitic nematodes the fall prior to all vegetable crops, especially carrots.

- Collect 20 sub-samples using a soil probe, shovel or trowel in a zigzag pattern 6-8 inches deep. Place the samples in a bucket and mix thoroughly for a composite sample.

- Take the composite soil sample and place about 1 quart of it in a container that retains moisture, like a plastic bag. Store in a cool area away from sunlight until shipment can be made to the laboratory.

- If samples are collected prior to harvest, gather six to 12 carrots from the margins of the problem areas. Remove the tops and place the roots in a plastic bag with soil and either deliver or send to the lab.

Your strongest asset is information. For more of that, check out the “Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for Commercial Growers.”

References

- Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for Commercial Growers

- Nematode Management in Tomatoes, Peppers, and Eggplant, University of Florida IFAS Extension

- The Northern Root-Knot Nematode on Carrot, Lettuce, and Onion in New York, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Print

Print Email

Email